by admin | May 25, 2021 | Opinions

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

The Who’s Who of Indian literary circles assembled at a five-star hotel here earlier this week to attend the announcement of the winner of the inaugural edition of the JCB Prize for Literature — conceptualised on the lines of the Man Booker Prize — at a specially curated dinner. It was a saga steeped in hypocrisy.

This correspondent confirmed his presence at the last moment and was allotted a seat. Next to me was a Public Relations executive from Britain, who had flown in to explore ties with the prize, seeking to establish opportunities for the shortlisted books — Perumal Murugan’s “Poonachi or The Story of a Black Goat”; Shubhangi Swarup’s “Latitudes of Longing”; “Amitabha Bagchi’s “Half The Night Is Gone”; Anuradha Roy’s “All The Lives We Never Lived”; and Benyamin’s “Jasmine Days” — in the UK. Or so he said.

Fortunately for me, he had attended the Booker Prize dinner, which is touted globally for its extravagance and the luminaries who attend it year after year. “But even by Booker standards, this is too grand,” he said, adding that nobody in the UK would spend this kind money on such an event.

On seeing the name inscribed on the table card of the person to my left, I realised we had exchanged several emails and had engaged in conversations over telephone but never met in person. He was earlier a publicist and was now writing for a leading website. I introduced myself — and we laughed at the coincidence of finding ourselves next to each other. The lady sitting across me was a known face too — a regular on the festival circuit — and looked at me curiously. I could sense that she wanted to initiate a conversation but just then a well-dressed man in an extravagant outfit, walked up to the stage to begin the evening’s proceedings.

He was the British Indian novelist and essayist Rana Dasgupta, the Literary Director of the prize. He welcomed the audience, introduced the prize and left everyone in suspense, saying the prize would be announced when the main course was served.

Most people in attendance had not known who he was before the announcement of this prize, but he was surely the one in limelight and journalists seeking to interview him had a tough time as requests were not entertained. Dasgupta had his own company to keep, and was surrounded by bigwigs for most of the evening.

Back at the table, the lady sitting across me, finally said: “Have we met before?” I reminded her that I had interviewed her on the sidelines of the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa two years ago — and that we had just been introduced by, let’s call him “the man of books”, before the doors of the hall were opened for the evening, about half an hour ago. How could she forget so fast?

Let’s rewind. The time stated on the invitation was 7.30 p.m. and proceedings began a little after 9. The period in between was when wine did all the talking and informal networking ruled the roost. Debutante Shubhangi Swarup walked around graciously in the company of a reader or two; her proud publisher, Udayan Mitra of HarperCollins, waxed eloquently on publishing her; Poulomi Chatterjee, Editor-in-Chief of Hachette India represented Anuradha Roy, who could not make it to the evening due to a prior commitment; and several other literary heavyweights graced the evening.

NITI Aayog CEO Amitabh Kant could be seen interacting with Lord Bamford, Chairman of JCB, ensuring that he was well in the camera frames. Writer Perumal Murugan, on the other hand, seemed out-of-place. So were several others, but they didn’t show it. Murugan’s dicomfiture was evident.

So what were the top notch of Indian literary circles discussing over wine? That the #MeToo movement has derailed many, that there is a need to separate art and the artist, that literary festivals could not, and should not, single out people on the basis of mere allegations, and that such a glamorous event was long awaited for Indian writing. Ironically, most of these very same personalities have an altogether different outlook on social media and when on stage.

Just as the main course arrived, the winner was announced — Benyamin for “Jasmine Days”. My phone buzzed with twitter notifications almost instantly while I hurriedly emailed a brief report to the newsroom. When I looked up, the crowd was gone, but the food was not. Hardly had anybody finished their meal, drinks had done all the talking all evening.

There is nothing wrong with cocktail evenings, but the suggestion these define the Indian literary space is absurd; and yet they have become synonymous with almost every literary gathering of our times. A literary prize like the JCB should first look at the vast magnitude of Indian writing arising under acute circumstances — in poverty, stress and in unfavourable conditions. One can well bet that the amount spent on the publicity of the Prize exceeded the amount paid to the winner. Turn towards the Sahitya Akademi awardees and the futility of the concept will be evident.

All of this may have been because the Prize is a mere excuse, and not the actual goal. The goal, it seems, is brand building — and that was exactly what was achieved on that glittery evening in the National Capital. If it was not so, the conceptualisation of the Prize must have been a lot different than what it was.

The Man Booker Prize is not an ideal formula to imitate, particularly in the Indian context that is so full of diversity and comprising mostly ignored writers (barring the privileged few, who hover from one festival to another). The JCB Prize did not break this mould, instead it once again underlined the biggest problem for a majority of writers in India — that just a handful rule the roost through a strange monopoly of literary agents, publishers, festival organisers as well as major awards. The JCB Prize for Literature is a new member of the same gang.

And lastly, did the Prize boycott Penguin Random House India, or did the publisher boycott the prize? No one will say a word, (for now) but something fishy surely happened within.

(Saket Suman is a Principal Correspondent at IANS. The views expressed are personal. He can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in )

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books, News, Politics

New Delhi : The Urdu version of the book “Exam Warriors”, penned by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, will be launched at an event here on Saturday.

New Delhi : The Urdu version of the book “Exam Warriors”, penned by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, will be launched at an event here on Saturday.

The programme is being organised by India Islamic Cultural Centre. Several cultural programmes will also be presented during the event.

The Urdu version of the book will be very helpful for a large section of Urdu language students.

In “Exam Warriors”, Prime Minister Modi has given 25 mantras to parents and students for dealing with stress during examinations.

He has advised the students to celebrate exams as festivals, face the exams with fervour and become a ‘warrior’ and not a ‘worrier’.

Modi has also talked about yoga exercises and the importance of quality sleep for students to beat stress.

The Urdu version of the book will be launched in the presence of Union Human Resource Development Minister Prakash Javadekar, Union Minority Affairs Minister Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi, Petroleum Minister Dharmendra Pradhan, actor Rishi Kapoor, filmmaker Muzaffar Ali, actor Annu Kapoor, and India Islamic Cultural Centre President Sirajuddin Qureshi.

Written in a fun and interactive style, with illustrations, activities and yoga exercises, the Hindi and English versions of the book have been well received by students and parents alike.

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Markets, Networking, Online Marketing, Social Media, Technology, Urdu

San Francisco : Artificial Intelligence (AI) researchers at Facebook have set a new record in improving translation from Urdu to English.

San Francisco : Artificial Intelligence (AI) researchers at Facebook have set a new record in improving translation from Urdu to English.

Neural Machine Translation (NMT) is the field concerned with using AI to do translations in any language.

The team from Facebook AI Research (FAIR) has seen a dramatic improvement in its results, the Forbes reported on Saturday.

“To give some idea of the level of advancement, an improvement of 1 BLEU point (a common metric for judging the accuracy of MT) is considered a remarkable achievement in this field; our methods showed an improvement of more than 10 BLEU points,” the team said in a paper that described translation from Urdu to English.

Facebook AI researchers seek to understand and develop systems with human-level intelligence by advancing the longer-term academic problems surrounding AI.

The research covers the full spectrum of topics related to AI, and to deriving knowledge from data: theory, algorithms, applications, software infrastructure and hardware infrastructure.

“Long-term objectives of understanding intelligence and building intelligent machines are bold and ambitious, and we know that making significant progress towards AI can’t be done in isolation,” said researchers from FAIR.

FAIR researchers have tested a new approach that teaches bots how to chit-chat like humans.

Facebook is making deep investments in AI technology and in May announced the next version of its open-source AI framework for developers.

Microsoft is currently leading when it comes to AI and Deep Neural Networks to improve real-time language translation.

Earlier this year, Microsoft brought machine learning to improve language translation for Hindi, Bengali and Tamil.

With Deep Neural Networks-powered language translation, the results are more accurate and the sound more natural.

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | News

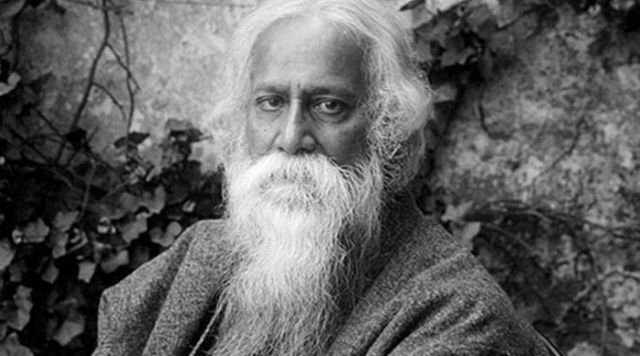

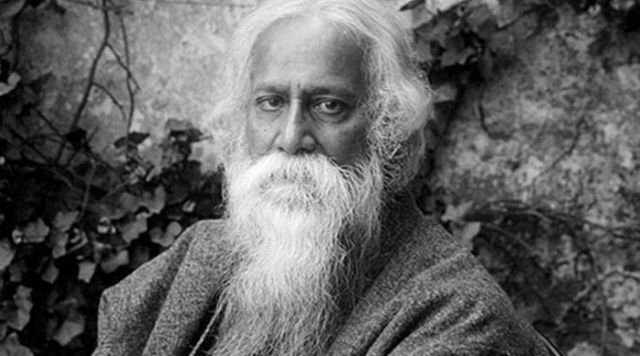

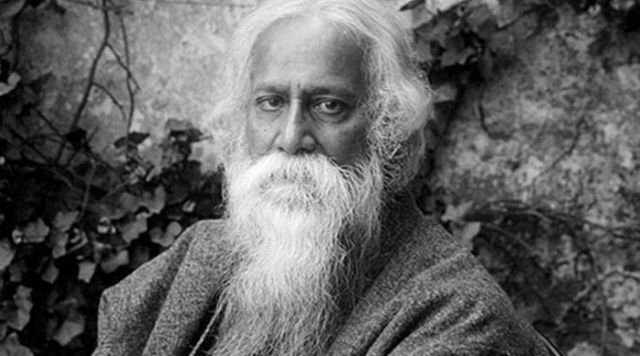

(August 7 is Rabindranath Tagore’s 77th death anniversary)

(August 7 is Rabindranath Tagore’s 77th death anniversary)

By Somrita Ghosh,

New Delhi : A progressive writer, visionary, a social thinker, a philosopher, an educationist – Rabindranath Tagore was a polymath. And it is this vastness that fascinated author Radha Chakravarty to take translate Tagore’s writings from Bengali to English.

As of today, Chakravarty is credited with translating eight works of the Nobel Laureate including “Essential Tagore” (with two others), “Gora”, “Boyhood Days”, “Chokher Bali”, “Farewell Song: Shesher Kabita”, “The Land of Cards: Stories, Poems and Plays for Children” and others.

Chakravarty had no formal training in Bengali. Her father had a transferable job which took her to different parts of India apart from West Bengal.

“But Tagore always remained as an influence at our home, no matter where we were. It was my grandfather who used to read out stories of his, that is how I started knowing about him,” Chakravarty, a Professor of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies in Delhi’s Ambedkar University, told IANS.

Chakravarty, the wife of former Indian High Commissioner to Bangladesh Pinak Ranjan Chakravarty, recollected her first encounter with Tagore’s writing was “Sahaj Path”. However, it was “Kabuliwalah” that drew her closer to the writer.

“I couldn’t realise how and when Tagore became a part of my life. I started reading more and more of his writings. What captivated me more was his choice of simple language and clarity in thought and approach,” she said.

But what really made Tagore a part of her life was the emancipation of women in the 19th century that reflected in his writing, which was not so prominent in the works of other writers, Chakravarty explained.

“His characters – be it Binodini of “Chokher Baali” or Labanya of “Sesher Kobita”, all had a distinct identity who tried to break societal norms and stood up for their freedom of expression, they had a question in their mind, they were rebels in their own way,” she noted

However, it was not Tagore that Chakravarty translated first.

“While teaching English literature in Delhi University I was simultaneously doing research work on many other Indian literary figures. I was approached by an upcoming publishing house to do a translation. And the first book happened which was a compilation of the works of 20 contemporary authors,” she said.

“Chokher Bali” was her first translation of a Tagore work and what appealed her to take it up was the enigmatic personality of female protagonist, Binodini.

“The character has multiple layers in her. The book was far ahead of time. The characters challenged the convention and family bounds. This further inspired me to take up his works and translate,” she stated.

Talking about translation, Chakravarty said that it acts as a major medium in strengthening cross-cultural bonds, adding that the scenario in the literary space has changed quite a lot compared to what it was few years ago.

“Now the publishers are welcoming it, which earlier was not there. The publishing houses would never show much eagerness in printing a translated work; it would take quite some effort to convince them, but now it is changing,” she added.

While translations on the one hand take regional literature to the world, Chakravarty highlighted on the several factors that need to be considered before taking up a literary work, particularly maintaining the ethos and values of the original writing.

“The time period of a book matters lot. The book talks about a scenario which existed in 19th or 20th century but the translated work will be read by 21st century readers. Therefore, the language has to be simple which can connect to the contemporary readers,” she explained.

Chakravarty pointed out that a linguistic barrier will always exist when it comes to translating from one language to English or from any other vernacular language, adding that translation is interpretation rather than mechanical transformation.

“Translating certain terms are often difficult like some expressions or words associated with culture or traditions which don’t have any alternative. There is a dilemma on how to put that in English. This is often pretty time-consuming,” she commented.

Although the non-translated words are always defined in summary, Chakravarty added that the certain original words bring in a different flavour to the translation.

“If something is left unexplained it adds mystery and generates curiosity among the readers to know what that particular word would mean. It pushes your imagination and in the process one gets a chance to learn a new word as well,” she said.

(Somrita Ghosh can be contacted at somrita.g@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Entrepreneurship, Interviews, Women Entrepreneur

Malayalam author Chandrika Balan

By Vishnu Makhijani,

New Delhi : Writings in Indian languages are more authentic than in English because they present a truer picture of Indian life, says multi-faceted Malayalam author Chandrika Balan, whose oeuvre includes 20 books in her mother tongue and four critical books and 36 research papers in English — and two of whose books have been converted into movie screenplays.

“Literature written in Indian languages can be said to be more Indian than Indian writing in English, for it writes more local colour realism and presents a cross-section of Indian life,” Balan, who has also translated widely from English to Malayalam and from Malayalam to English and has received the Katha National Award for English translation,” told IANS in an email interview.

The Sahitya Akademi, eminent publishers and reputed journals in India “give enough importance to translated works now. Translation has become part of academic syllabus too. So the situation is hopeful,” noted Balan, whose latest offering “Invisible Walls” (Niyogi/128 pages/Rs 250), the English translation of Malayalam title “Aparnayude Thadavarakal”, has just been released.

How did the present work come about?

“I began writing it as a short story as I am mainly a short fiction writer. The story started as Kamala’s; Aparna was not there in the picture at all. But then Aparna entered the story half way as Kamala’s friend and soon claimed the story as her own. When I developed the characters, the work became longer and turned out to be a novel, portraying two women who fight invisible walls,” she explained.

To elaborate, “Invisible Walls” is about two women, Aparna and Kamala, whose lives run in parallel, though they do not know each other. They dream of a world without walls, but invisible barriers surround and crush them. Kamala reads a book titled “Invisble Walls” about Aparna’s life on a train journey and thus the reader discovers a story within a story.

Given this theme, Balan, formerly a Professor of English in Thiruvananthapuram’s All Saints’ College, said Malayalam literature today, “especially the scenario of fiction, is full of variety in themes and forms of expression. Earlier, only literature written by Indians in English was considered Indian English literature. Now that Indian literature in translation is being given the importance and attention it deserves, our literature is also on the way of being promoted”.

How did the translating bug bit her?

Balan, the recipient of 15 awards, including the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award, the Katha National Prize, the Padmarajan Puruskaram and the O.V. Vijayan Puraskaram, said that while she previously did her creative writing only in Malayalam, she took a break from her teaching career for three years to work with Dr K. Ayyappa Paniker, the renowned English professor, poet and critic, on a Sahitya Akademi project on Medieval Indian Literature in English translation.

“I was the Executive Editor of that project. Editing the translations of eminent professors and writers from all parts of India, I educated myself on the art of translation. Katha Foundation of Delhi asked me to translate some Malayalam writers of their choice to English. When they were published, more offers came; but somehow I did not want to be a professional translator. I wanted to be known as a creative writer. So I took to translating my own stories.

Her first collection, “Arya and Other Stories” was published by Orient Blackswan.

Would she describe herself as a systematic writer?

“I am not a systematic writer at all, devoting a number of hours a day for writing. My dream is to become one. When an idea comes to mind, I develop an outline first and carry it around like a child within the womb. And when the urge for writing it comes upon me I sit late in the night to write down the first draft. The reworking and revisions will be done later; usually it is the third draft that is final,” Balan explained.

How did the foray into the movie world come about?

It began with noted Malayalam film director and screen writer Lenin Rajendran making a movie out Balan’s story “The Website” as “Ratrimazha” (“Rain in the Night”) “which brought him accolades. He has taken a Director’s freedom with the story”, Balan quipped.

Her book, “Njandukalude Naattil Oru Idavela” (An Interval in the Land of Crabs) has recently been made into a similarly titled movie by the popular young actor Nivin Pauly, with the director being Althaf Salim.

“That book is actually my memoirs on my cancer days; they turned it into a family story of a mother’s fight with cancer and brought in a lot of humour. But they conveyed the message of hope as I insisted,” Balan said.

She has also written a screenplay for Kerala’s Social Welfare Department, which turned it into a movie directed by Sanjeev Sivan.

“It is titled ‘Arunimayude Katha’ (The Story of Arunima); the theme is a critique on the extravagant weddings and craze for gold in Kerala,” Balan said.

Her dream now is “to write two novels — one on a village being transformed into a city and the other on (Russian author Leo Tolstoy’s wife) Sonia Tolstoy. Both require a lot of time and work and I intend to devote 2019 to that”, Balan said.

(Vishnu Makhijani can be contacted at vishnu.makhijani@ians.in)

—IANS