by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

Book: Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan; Author: Ruby Lal; Publisher: Penguin-Viking; Pages: 308; Price: Rs 599

For certain generations of Indians, the cinematic fable of Anarkali is perhaps the most celebrated, but cliched, introduction to royal court intrigues of the Mughal era, in which an enraged Emperor Akbar orders the confinement of Shehzada Salim or Jehangir’s lover and semi-fictional heroine in a nondescript portion of a wall at the Lahore fort, following an elaborate courtship, including song and dance.

Ruby Lal’s biography “Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan” in many ways tries to throw the spotlight on the real heroine of the life and times of Jehangir: His empress Nur Jahan.

Lal, in her feminist biography of the Nur Jahan — born Mihr un-Nisa — underscores her worth in the otherwise overwhelmingly male-dominated annals of the Mughal empire, which have invariably spoken about the men who wore the crown and defined the destinies of the millions who lived in their empire.

Nur Jahan, according to Lal, was everything every Mughal empress, before and after her, wasn’t.

A warrior who led troops into battle, an expert horse-rider, a widow who ended up marrying an emperor, an empress who issued royal proclamations and who had royal coins with her name etched on them. And when push came to shove, also rescued Jehangir after he was imprisoned by one of his officers.

Lal’s approach in chronicling Nur Jahan is an interesting one. By using historical fact as an easel, the author paints rich, vivid, descriptive strokes of Nur Jahan’s journey from the daughter of a relatively nondescript and persecuted Persian nobleman, their perilous travels to the Mughal court in Lahore and her dramatic rise to becoming the Empress of the mighty Mughal Empire.

“Asmat and Ghiyas would have walked along the streets crowded with houses, perhaps exploring the bazaars, that pulsates with energy, packed with buyers and sellers, and passersby exchanging greetings and the news. One section of the bazaar, a series of intricate lanes, was set aside for women only. Women took their time gazing at the bold patterns and colourful embroidery on the finest muslins, silks and velvets. Many wore flowers in their hair, and toe rings and anklets with charms or little bells and chewed betel leaf to redden their lips. Married women wore maang, red colour in the parting of their hair; or the sekra, seven or more strings of pearls that hung from a band at the forehead or the laung, a clove-shaped stud ornamenting the nose” is how Lal evocatively describes the scenes which Nur Jahan’s parents would have encountered in 16th century Lahore, a flourishing centre of trade and a beacon for the persecuted Persian parents, whose daughter in the decades to follow would be the Empress of the Empire.

The book also puts into context different narratives about the rise of Nur Jahan, while laying down antecedents of the chroniclers of the time, thus allowing the reader to gauge and understand the political and historical context to the narrative.

For example, while summarising three parallel narratives about a snake threatening a just-born Mihr un-Nisa, she says: “An Italian quack doctor, an Indian courtier, a Scottish adventurer — each wrote of Nur Jahan’s birth. The Catholic mercenary Manucci (Italian) was interested in an imitation of Christ. For Khafi (courtier), the Indo-Persian tales of migration and a man’s compassion for his wife were dominant. Alexander Dow (Scotsman) and the early colonial writers who followed him were enchanted by a romantic image of India, that land of wonders, surprises — and snake charmers.”

“Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan” is a rare lyrical read about a dashing woman who not only smashed the prevailing high walls of conservatism of her time, but whose influence is also unfortunately overshadowed in India by the romance of a Jehangir’s semi-fictional lover, Anarkali.

(Mayabhushan Nagvenkar can be contacted at mayabhusha.n@ians.in )

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

Book: Full Disclosure; Author: Stormy Daniels; Publisher: St. Martins Press/Pan Macmillan/Pages: 270; Price: Rs 699

In a tell-all memoir that justifies its title “Full Disclosure”, porn star Stormy Daniels makes stunning claims about US President Donald Trump, dwelling on his psyche, wondering whether he is fit to hold the world’s most powerful office, and detailing his body in a manner that will be clearly seen as “not cool” by the man she had the most unimpressive sex with ever.

Daniels notes that she felt utter disbelief when Trump kicked off his election campaign, and then went on win the Republican nomination in 2016. Several other adult stars who had not met Daniels for years but were aware she had slept with Trump in 2006, began to call her, and they were, according to Daniels’ telling, as surprised as she was.

“It will never happen, I would say. He doesn’t even want to be President,” she writes, describing her initial reaction to his nomination.

However, as Trump kept winning primary after primary, a sudden fear began to grip her. She knew that she held one tight secret about Trump, which he might not want the world to know and, therefore, felt she was in danger.

She claims that she had been threatened once by Trump several years ago and was strictly warned to never spill the beans. She says she was not supposed to tell anybody that she slept with Trump, who warned her to “never tell the story”.

These fears and her decision to sign a $130,000 hush agreement feature in the book along with an explicit description of sex with Trump.

“He needs to shave his balls,” was her first thought before the two would consummate. What Daniels writes thereafter, according to her, is the reason Trump did not ridicule or “oust” her prior to her taking on him in public.

“His penis is distinctive in a certain way, and I sometimes think that’s one of the reasons he didn’t tweet at me like he does so many women. He knew I could pick his dick out of a line-up,” she writes.

So, how was sex with Trump?

“I’d say the sex lasted two or three minutes. It may have been the least impressive sex I’ve ever had but clearly, he didn’t share that opinion. He rolled over and said, ‘Oh, that was just great.'”

Despite the underwhelming sex, she continued to answer Trump’s calls over the next few years, hoping that he would fulfill his promise to put her on his reality show, “The Apprentice”.

According to Daniels, Trump had even suggested that unfair means could be applied to keep her in the show, as it was he who was running the “show”.

“He was going to have me cheat, and it was 100 per cent his idea,” Daniels claims. Every time that she would see Trump on television thereafter, she would be reminded of the sex she had with him. Even the memory was disgusting, she adds.

Major portions of the book revolve around her coming to terms with the fact that she needed to go public with her story about Trump. Doing this meant first revealing it to her then-husband. Ultimately she did so, and that too just before the elections.

While the timing can be construed as being politically motivated, Daniels argues that she did it for her and her daughter’s safety. They would be less vulnerable to attacks if people knew the identity of the only person who had a reason to harm her, she argues. She also recounts an incident when she was approached by a well-built man at a parking lot, adjacent to a gym, who warned her never to let the story out.

The memoir ends on a tragic note, when readers learn of Daniels’ divorce and separation from her daughter. She is resilient, nonetheless, and hopes to sail through.

The memoir was first published in the US by St Martin’s Press earlier this year and has just arrived at Indian bookstores through Pan Macmillan. About the portions detailing Daniels’ tryst with Trump, it should be noted that it is one side of the story, filled with humour, satire and criticism, and may not present the events in their totality, or reality.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Tarun Basu,

By Tarun Basu,

Title: India and EU: An Insider’s View; Author: Bhaswati Mukherjee; Publisher: ICWA/Vij Books; Pages: 358; Price: Rs 746

About a decade ago, the European Commission, troubled perhaps by the not-so-positive perception it has in India, decided to set up what it called a “Indo-EU news agency” to produce and disseminate real-time, accurate and informative news from the EU to India and perhaps vice versa.

After a lot of endless discussions within the notorious EU bureaucracy, they chose an Indian journalistic trade union body with little experience of dealing in international news, over the claims of some professional news agencies, for its partnership.

The enterprise, predictably, did not last too long and the perceptions remained, according to Bhaswati Mukherjee — resulting in a “continuing challenge” with general “lack of visibility in the Indian media regarding the EU” and a general “negative tone” which some experts have said bordered on “disapproval and general indifference”.

Mukherjee, who retired as Indian Ambassador to the Netherlands and also served in Paris as Ambassador to the Unesco, has spent the best part of her career trying to bring content and meaning to India-EU ties, which she thinks works much below its potential. In fact, she calls it “a faltering strategic partnership” in her seminal offering, “India and EU: An Insider’s View”.

Although Mukherjee says that the book is about “Europe meeting India”, it is actually an expansive and insightful tour d’horizon of India’s long engagement with Europe, such that has not been attempted to date, at least from the Indian perspective.

She gives the history, the different dimensions of the relationship, Europe’s intra-state dynamics, the trade block, the perception factor and, finally, the way to go.

As Hardeep Puri, former Indian diplomat and now minister in the Modi government, said, it was a must-read for anyone dealing with India-EU dynamics.

Speaking at the book launch, Puri said, tongue in cheek, that EU’s perception about India — and the way it dealt with it — would perhaps change if India becomes a $5 trillion economy. Despite common values of democracy, language, liberal institutions, etc., EU never resisted the urge to be “prescriptive” towards India, especially on human rights issues, particularly regarding Kashmir and India’s penal system.

One of the other strategic areas of difference, as Mukherjee points out, is the way the two sides viewed their partnership. India was slow to respond to EU overtures of a strategic partnership, mainly because New Delhi was reluctant “to become a pole in a new multipolar world”.

But slowly Indian thinking has evolved, especially under a nationalist administration, and Prime Minister “Modi has taken important measures to reinvent, redirect and reinvigorate India’s foreign policy imperatives”. The relationship has appeared to have gathered new momentum and will continue to blossom post-Brexit, especially with coincidental positions on climate change and global warming and founding of the International Solar Alliance (ISA) by Modi and French President Emmanuel Macron.

Mukherjee says ISA will “consolidate the India-EU strategic partnership”. The only irritant remains the proposed free trade agreement, or the Broadbased Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA) as it is officially known.

Despite 16 rounds of negotiations, the deal is stuck because, in India’s view, EU — being India’s largest investor and trading partner — is not ready for any “give and take” in the negotiation and refuses to relent on access to services, of which UK till now was the biggest blocker.

Whether Brexit in 2019 will remove this “impediment” — the British prism — finally remains to be seen. There are clearly two ways of looking at the India-EU partnership, of which no one denies there is huge untapped potential: While the EU remains optimistic largely, despite being tough negotiators in the board room, the Indian side remains sceptical and even cynical, with one former Indian ambassador to France publicly averring that the ties “had run its course” and it was high time “new ideas” were injected into the discourse to catch the imagination of the youth in both countries and bridge the “perceptional gap” that is obviating what should be a win-win relationship by all accounts.

But, as Mukherjee asks in her profound assessment, can the structural asymmetries and gaps be bridged by visionary leadership on both sides?

(Tarun Basu can be contacted at tarun.basu@spsindia.in )

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Mohammed Shafeeq,

By Mohammed Shafeeq,

Book: Shahryar: A Life in Poetry; Author: Rakhshanda Jalil; Publisher: HarperCollins; Price: Rs 599; Pages: 226

Shahryar (1936-2012) was arguably one of the best Urdu poets in the post-Independence era. Emerging as a poet in the 1960s, when progressiveness was drawing to a close and modernism was sweeping the literary scene, he carved a niche for himself even as he refrained from identifying with either of the two groups.

In this biography, writer, critic and literary historian Rakhshanda Jalil has brilliantly captured different aspects of Shahryar’s life, his works in the backdrop of “taraqqi pasand” (progressive) versus “jadeed parast” (modernist), his unique yet simple style of poetry and also his brief tryst with films.

Tracing Shahryar’s journey as a poet, the author demonstrates how he evolved a set of symbols, images and metaphors that, while seemingly personal, transcended the self and the individual to speak of universal concerns.

She believes that the brevity and succinctness in his description, and the softness and evenness in his tone, set apart Shahryar’s poetry from his contemporaries.

The author notes that unlike many Urdu poets, who used to coin new expressions with the use of hyphenated words, Shahryar’s short poems used to catch the reader’s attention with a simplicity that is startling and direct. For instance:

Bechi hai sehr ke haathon/Raaton ki siyahi tumne/Kii hai jo tabahi tumne/Kisi roz sazaa paoge (You have sold the ink of the night/To the morning/You will be punished some day/For the devastation you have wrought).

With her translation of Shahryar’s best ghazals and nazms in English, the author has introduced his poetry to a new generation while evaluating his considerable body of works.

According to her, the individualism and romanticism of Shahryar’s early years, as evident in his first collection of poetry, “Ism-e-Azam” (The Highest Name) published in 1965, soon gave way to an acutely felt concern for the world around him in subsequent collections such as “Satwan Dar”‘ (The Seventh Doorway, 1969) and “Hijr ke Mausam” (Seasons of Separation, 1978).

The author believes that while refusing to fully adopt the vocabulary of the revolutionary poets favoured by the progressives, he refused to write merely to satisfy his own creative self or ease the burden of his soul, thus differing sharply from “jadeed parast” as well.

The book also encompasses the early life of Kunwar Akhlaq Muhammad Khan, who later took “Shahryar” as his nom de plume. Under pressure to follow in the footsteps of his father and join the police department, this Rajput boy from western Uttar Pradesh left the family home in 1955 and lived with Khalilur Rahman Azmi, his friend and mentor who spotted his poetic talent and encouraged him to write.

Shahryar had begun writing poetry in the final year of his BA at Aligarh Muslim University.

The book also refers to the legendary rivalry between Shahryar and Rahi Masoom Raza. Both were contenders for the coveted post of lecturer at Aligarh University and it was Shahryar who bagged it while Raza moved to Mumbai where he earned name and fame in the film and television industry.

With his debut collection of poems “Ism-e-Azam”, Shahryar established himself in the world of Urdu poetry and a flattering review by Gopi Chand Narang gave him the sort of international recognition that few poets of his time could hope for.

The author observes that while Shahryar wrote only in Urdu, there was nothing in his oeuvre that makes an explicit call to any one community. “If ever there is a writer who can most effectively debunk the absurd misconception that Urdu is the language of Muslims or the cultural repository of Muslims alone, it is indeed Shahryar.”

In a literary career spanning five decades, Shahryar always managed to remain topical and his poetry could always be termed “the call of the time”. A self-confessed Marxist, Shahryar was, however, not an atheist.

The author believes that Shahryar’s film lyrics have caused him as much harm as the fame they brought his way. While his songs made him a household name and enabled his words reach all nooks and corners, it must also be acknowledged that in the popular imagination, he became etched as a lyricist and not a poet of gravitas and merit.

“That four films should cast such a long shadow over a poet who produced six highly regarded volumes of poetry and two different editions of critically acclaimed collected works is, to my mind, an injustice to a poet of Shahryar’s calibre,” the author concludes.

(Mohammed Shafeeq can be contacted at m.shafeeq@ians.in)

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

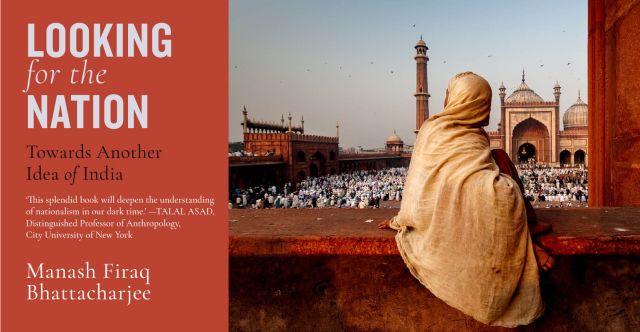

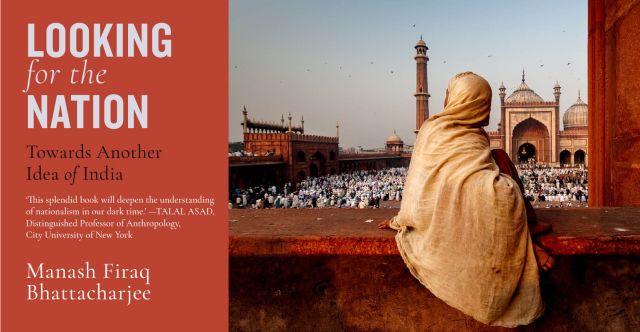

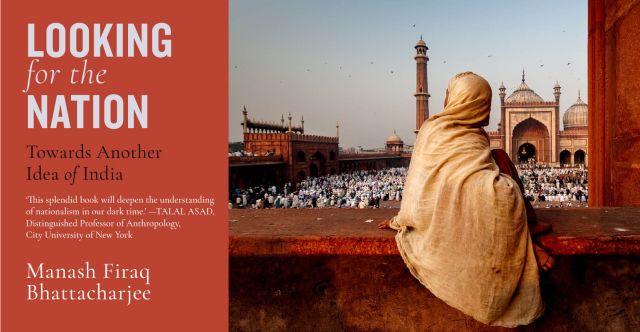

Book: Looking for the Nation; Author: Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee; Publisher: Speaking Tiger; Pages: 202; Price: Rs 350

Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee, who earned his doctorate in Political Science from Jawaharlal Nehru University and has been published widely in national and international media, was haunted by a ghost during his childhood. Several decades on, the political theorist has come out with a scholarly offering — backed by research and reading — as his act of resistance against the ghost.

The author grew up in a small town in Assam and one of his father’s friend, a retired railway employee, was a frequent visitor to their house. For reasons yet incomprehensible to the then young lad, this old man, and his politically sanctioned method, would cast a harrowing shadow on his upbringing.

To put things in perspective, the old man would customarily narrate stories about the violence of Partition, that erupted after India and Pakistan were separated at birth. But his stories “inevitably revolved around Muslims attacking hindu villages,” and the resistance strategies that Hindus evolved to ward off the attack.

“I remember one particular incident he narrated, where scores of bricks were stored on the terraces of Hindu households… When the Muslims attacked, the bricks were put to effective use. “We never wondered why he chose to tell a 14-year-old boy and his sister stories that would shake them to the bone,” he recalls in “Looking for the Nation: Towards Another Idea of India”.

Many years later, Bhattacharjee realised that the telling of such harrowing, sometimes skewed, stories were a part of “a deliberate plan”.

“The man, I learnt much later, belonged to a Hindu right-wing organisation. The stories he told us were part of his job. His job was propaganda. This was a politically sanctioned method to arouse and cement communal sentiments,” he reflects in the book.

But “his lies and fantasies” have caught on with the author’s present and he penned this book, “not looking for a desirable idea of the nation”, but in the quest for “the nation with irony, discovering everything that falls short of fraternity and justice”.

And how does he do it? Fortunately, Bhattacharjee’s offering breaks from the routine books that either blindly critique the functioning of Hindu right wing organisations, or are full of praise for them. His book is neither criticism, nor reflection, if anything, it is an earnest attempt at understanding how our country functions, not in accordance with what is laid down in the Constitution, but in practise in our day-to-day lives.

His arguments are broken down in six chapters, each tracing a particular trajectory that has gone in, or continues to shape, the elusive idea of India.

In the first chapter “The Surplus of Indian Nationalism”, his findings suggest that Indian nationalist thought is a product of the anti-colonial movement. In finding the root and evolution of Indian nationalism, he keenly studies the works of Nehru, Tagore, Gandhi, Ambedkar and others, who, through their participation in the freedom movement, gave voice to the sentiments of nationalism.

He explains that Nehru, in his writings, laid down the larger debate of nationalism, and its relation with modernity, culture, identity and history. Aurobindo, on the other hand, reflected on the nation as “a grand idea in the shadow of religious differences”. The chapter also suggests that Tagore engaged with Gandhi on the question of culture and universalism, while Ambedkar provided a critical perspective on the speculations by nationalist thinkers.

After having laid down the foundation of his research in the first chapter, Bhattacharjee strolls down the “territory without justice”. “…Since then (Independence), the stories of betrayal, hatred, and above all, the fetish for territory, haven’t come to an end”, he notes, before analysing the fate and predicament of the nation’s most “beleaguered people” — the refugees, the Dalits and the minorities.

In the next chapter, he looks at India’s Muslims, with the shadow of Partition behind them, and the future ahead. “The discourse of trust and mutual generosity were taken over by suspicion and hatred. Religion and history were treated as contested territories of difference,” he writes in charting what has “led to the sacrifice of ethical responsibility”.

The remaining chapters focus on “Untouchables”; the institutions of the country, where he finds that bodies are coerced through mechanisms of control; and “Thinking Against Power”, the last chapter of the book, throws light on the resistances against nationalism, caste and other embedded patriarchies.

“Looking for the Nation”, however, may come across as too heavy for some readers, flooded as it is with analogies, reflections and studies of various thinkers and leaders. This book’s merit lies in its structure, and the author succeeds in telling what he set out to do, by dividing the book into six chapters, each focussing on one theme and leading, quite naturally, on to the next.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS