by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Arun Kumar,

By Arun Kumar,

Book: Open Embrace: India-US ties in the Age of Modi and Trump; Author: Varghese K. George; Publisher: Penguin Random House India; Price: Rs 599.

Donald Trump’s “America First” politics with its anti-Islamism focus and Narendra Modi’s nationalist agenda forged by the so-called “Hindutva Strategic Doctrine” make the two so dissimilar world leaders “natural allies”.

That’s the premise on which Varghese George, US correspondent for The Hindu, has tailored his book to suggest that the Modi-Trump brand of politics would likely continue to shape India and America and their relations long after they have gone.

Like a lawyer’s brief, he has marshaled arguments with painstaking research to back his theory. But in the absence of counter-arguments, it often seems a stretch.

For instance, Trump, he suggests, has sought to make a critical change to the racial politics of America, somewhat like what Modi has done to caste politics in India. And both are also clear about a “global civilizational alliance”.

While previous Indian Prime Ministers, including the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) Atal Bihari Vajpayee, sought to package changes in Indian foreign policy directions as improvements, both Modi and Trump keep projecting themselves as changers even when nothing changes.

But unlike Trump, who has spawned “resistance” at home, this prospect of change seen in Modi’s speech to Congress about US and India overcoming “hesitations of history” has united lovers and haters of Obama and Trump in fractious Washington in admiring Modi.

If the Modi-Obama hugs fostered a joint strategic vision to challenge China in the Indo-Pacific and the Indian Ocean region, his bonhomie with Trump was seen in America as an “open embrace” for resisting “China and setting the global agenda”, says George.

But unlike “greenhorn” Trump, who has no ideological moorings, Modi’s world view must be influenced by what George calls a Hindutva Strategic Doctrine.

This doctrine, according to George, imagines India to be a natural homeland of all Hindus with refugees from other religions seen as “infiltrators”. Trump too has sought to make a similar distinction between Christian and Muslim refugees seeking asylum in the US.

While US-India relations have been on an upward trajectory since the lifting of post-nuclear test sanctions, George suggests Trump and Modi are likely to build a relationship that will bring India and America too close for comfort.

The author also makes a vary valid point that the charge of a Russian hand in getting Trump elected has not only undermined his authority, but an anti-Russian hysteria, fueled by the mainstream media, has also gripped the American traditional strategic community.

Trump and the American establishment undermine each other on relations with Russia and Iran, cumulatively weakening America’s position in Afghanistan as well, he suggests. This has also affected India-US relations.

Interestingly, George recalls how after touring across the US, he and another Indian journalist chose to go to the Trump election headquarters on election day when pollsters, pundits and the press were predicting a Hillary Clinton win.

Apparently, sometimes it takes an outsider to see clearly.

(Arun Kumar was till recently the Washington correspondent of IANS. He can be contacted at arun.kumar558n@gmail.com)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

Book: Kasturba Gandhi; Publisher: Thornbird; Pages: 424; Price: Rs. 795

The woman who silently and patiently stood by the Father of the Nation, supporting Mahatma Gandhi’s grand plans to free India from colonial rule, as well as his quirky habits, finally finds a voice in Giriraj Kishore’s book “Kasturba Gandhi”.

Translated by Manisha Chaudhry from the author’s novel originally written in Hindi, a fictional biography of the woman in whose companionship Gandhi scripted chapter and verse of India’s freedom struggle, puts a much-needed spotlight on Kasturba’s life, which is more often than not relegated to virtual anonymity in comparison to the attention and focus on the life and deeds of her husband.

The fictionalised work, weaves in and out of her real life, tries to build context and accentuates the substance which the Porbandar-born “Ba” was really made up of.

Especially in the light of the fact that while Bapu sacrificed immensely for the country and earned his legacy, Kasturba in some ways sacrificed much more, both for the country as well as for her husband, and yet remained relegated to the fringes of history and popular attention.

The fictionalised biography covers her entire life, right from the time she is growing up as Kastur Makanji, a neighbour of the Gandhi family in Porbandar in the 19th century, when many Gujaratis looked to the Africa continent for trade, especially in cotton.

After her marriage at 14 to the man who would shape the destiny of then British-ruled India, the book first drops anchor in Africa, where she earns the distinction of being the first Indian woman to face a jail sentence on foreign soil in her fight for basic rights for Indian women.

Interestingly, while the book largely focuses on the personality of Kasturba Gandhi, it also provides a perspective on the role Gandhi played as a man with his family, his relationship with his wife, his children and the role he played as a father — one which has been under scrutiny in the past.

The subtle conflicts between Kasturba, a quiet, devoted wife, and Mohandas, the consummate selfless saint, are well put across by the author, the anecdote (fictional or not) about how Gandhi eventually came to drink goat’s milk being a case in point.

Kishore builds up the context to the goat milk episode with the dilemma faced by Ba, arising out of Gandhi’s extreme positions.

“Ba was losing her fortitude. Bapu’s refusal to eat, not taking his chosen medicine, a second time, the doctor’s refusing to endorse his belief that he was going to die… all this was nothing but an exercise in self-flagellation. The person who could transform others to believe in non-violence was committing violence on his own heart and mind. Kasturba was also suffering this violence in her own way.”

The author then writes about a spell of illness which Gandhi had suffered, which had left him weak and in need of an operation. But according to the doctor, the operation could only be conducted after he regained a prescribed level of fitness, which required Gandhi to drink milk. However, Gandhi had in the past vowed against drinking milk on account of the violence inflicted by the dairy industry on milch cows.

The tactful and earthy Kasturba, however, had a way out of the pickle, which would help Gandhi keep his vow, but also ensure that some amount of milk would find its way into his malnourished body, so that he could carry on his struggle for satyagraha.

“Due to cruelty towards milch cows by the people in the dairy trade, he had taken a vow not to drink milk years ago. Nobody had been able to break his view. As Bapu spoke, Ba’s mind raced. After a pause she said calmly. ‘Fine, you will not have any objections to drinking goat’s milk?'”

The doctor caught on: “Yes, goat’s milk will be fine”.

For a moment, Bapu was nonplussed. He dug deep. Once more, he felt his life partner had stumped him with her normalcy. When he had vowed not to drink milk, goat’s milk had not figured in his calculations. He had only been thinking of cow’s milk. So he could consume goat’s milk keeping the vow intact. He would be able to start the satyagraha movement. Just the thought of that brought a surge of energy.

That evening Bapu had his first glass of goat’s milk.

The book provides the reader an interesting take on an era about which a lot has already been written about, but rarely from the perspective of those who played a vital role in the making of modern Indian history, albeit from the sidelines.

(Mayabhushan Nagvenkar can be contacted at mayabhushan.n@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

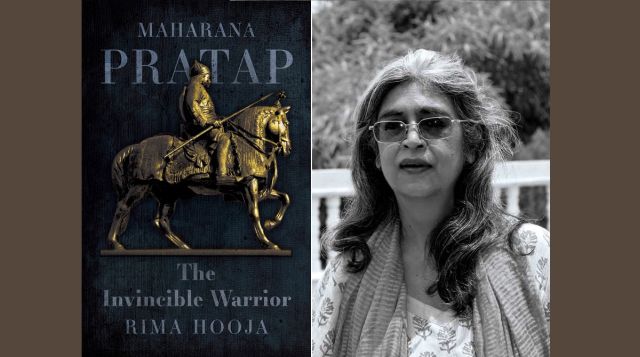

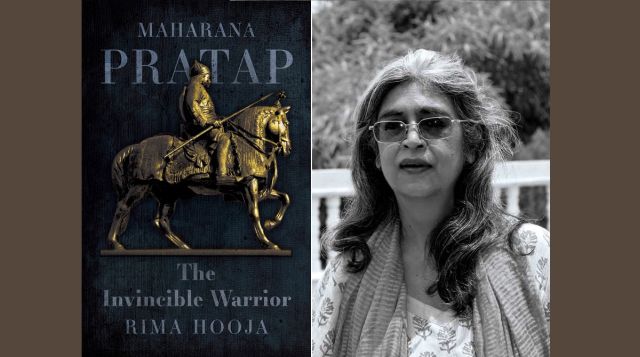

Book: Maharana Pratap – The Invincible Warrior; Author: Rima Hooja; Publisher: Juggernaut Books; Pages: 204; Price: Rs. 499

Who really won the battle of Haldighati? Did Maharana Pratap’s army and his Bhil tribals outnumber Akbar’s Imperial army? Did the Rajput king flee from the battlefield on his loyal steed Chetak or was it a strategic getaway? All of this, and more, is captured in this recent offering.

To those familiar with the heroic lore of the Mewar warrior, historian Rima Hooja’s book helps put into context his achievement as the man who valiantly withstood the might of the Mughal empire at its peak, despite being in banishment for large periods of his reign. And to those unfamiliar with his exploits, it helps visualise the life and times of the warrior and the battles and valour which earned him his place in history.

In many ways, Maharana Pratap of Mewar and Chhatrapati Shivaji of the Maratha region were warrior brothers, bound together with the blood history.

While Shivaji won over the services of his mavlas — bandied together from disparate castes and religions — Pratap who preceded him in time, was sheltered by Bhil tribals who he eventually recruited in his fight against the Mughals, along with Afghan warriors.

“Maharana Pratap – The Invincible Warrior” gives us an insight into his line of ancestry and his ascent as the Rana of Mewar, amid a period of uncertainty and strife in the Rajput kingdom.

While the book’s draw is the detailed depiction of the epic battle of Haldighati. The valley named after its turmeric colours terrain, in a way was a cleavage between the two chauvinistic egos of Emperor Jaluddin Muhammad Akbar, whose elaborate campaigns as well as all-powerful reign brooked no stopping and Maharana Pratap, the pride of Rajput sunkings, who would never bend to the imperial will of the Mughal ruler, keen on further expanding his footprint south of Delhi.

Hooja evaluates the strength of both Pratap’s army and Akbar’s force, quoting multiple historical references of the period and after it, which often contradict one another leaving the reader to weigh the options presented.

While historian and Mughal era translator Abd al-Qadir Badayuni claims that the Mughal commander and Rajput king Man Singh led a cavalry of 5000, Nainsi’s Khyat, an account written by Munhot Nainsi, a Marwar minister claims that Man Singh led a force of 40,000 soldiers. Another work by Kaviraj Shyamaldas says that the Mughal army had as many as 80,000 soldiers.

Similar inconsistencies dog the count of Pratap’s force.

Hooja however lays to rest one persistent doubt, that the Maharana’s Mewar army was outnumbered by Akbar’s forces when they clashed at the battle of Haldighati, which took place in June 1576.

The book also narrates details about how the battle, one of the most popularly known conflicts, was not all about swagger and bravado, with both sides also resorting to trickery to boost the morale of their soldiers in a battle, where fortunes swing one way and then the other.

“In the heat of battle, when the Mewar forces seemed to be gaining the upper hand, the Mughal commander Mahtar Khan spread the rumour that Emperor Akbar himself was approaching, leading a large contingent of the imperial army. Akbar was not present at any stage of the battle of Haldighati, but at that moment the ploy worked and boosted the morale of the Mughal forces who, instilled with fresh courage, rallied anew.

The Maharana’s flight from battle against his wish, to “live to fight another day” as well as the account of his steed Chetak also finds reference in Hooja’s book, which formally establishes several aspects of the warrior’s life, already a part of North Indian legends.

(Mayabhushan Nagvenkar can be contacted at mayabhushan.n@Ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By C. Uday Bhaskar,

By C. Uday Bhaskar,

Book: The Indian Empire At War; Author: George Morton-Jack; Publisher: Little, Brown; Pages: 582; Price Rs 699

World War I was a long and brutal military confrontation between the major powers of the early 20th century, fought across the trenches of Europe and in large swathes of Asia and Africa, resulting in the death of millions of hapless soldiers who became unwitting pawns in the great global “game”.

The four-year-long war that led to as many as 20 million dead and an equal number wounded ended on November 11, 1918, when an armistice was signed and a defeated Germany was compelled to accept closure. Over the last decade, there has been a spurt of interest among historians about the Great War; and the Indian contribution which remained relatively obscured has been brought back into focus. Undivided India, then a colony of the British Empire, contributed 1.5 million soldiers and non-combatants to this war and they served with distinction in all the major theatres. It is estimated that as many as 74,000 of them died in that war.

The book under review is among the more recent additions to this slim corpus on the Indian effort in the Great War and is both comprehensive and distinctive. As author George Morton-Jack points out, “This book is the first single narrative of it on all fronts, a global epic not only of the Indians’ part in the Allied victory over the Central Powers, but also of soldiers’ personal discoveries on their four-year odyssey.”

Neatly divided into six major chapters, the book provides the political context, beginning with the Delhi Durbar of 1911, in a lucid introductory chapter and the manner in which Herbert Asquith, then “Britain’s brandy-loving Prime Minister”, declared in Parliament on August 6, 1914: “We are unsheathing our sword in a just cause.”

But when they were swiftly recruited from different parts of British India to be shipped (like lambs to the slaughter) to distant lands in Europe — for many of these young men it was their first foray outside of their villages and small townships — they understood little of the complex politics about the War, intrigued about the “Jermuns” and, as Morton-Jack adds: “…the Indian ranks stoically suffered the Western Front’s rain and mud, cruelly catapulted by the fates into a war far from home that was never their own yet winning their fair share of VCs.” (As a contemporary aside, US President Donald Trump chose to avoid the rain and skip the centenary ceremony outside Paris on November 11, 2018.)

The VC (Victoria Cross) was awarded for the highest acts of gallantry in “the presence of the enemy” and this book empathetically records the incredible valour of the Indian “fauji” in the Great War. As the author recounts, in 1927, the Secretary of State at London’s India Office “favourably compared the Indian infantry in France to the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, ‘those whose valour was immortal'”.

However, this book is not only about the battlefield exploits of the Indian soldier but a multi-layered, rigorously researched and empathetically interpreted account of the Indian contribution to the Great War. The author’s objective of shining “a more filtered light on the Indian soldiers” is luminously met.

Pictures and maps embellish the value of this book and one of the more moving is that of an Indian cavalryman sharing his food with a local woman near Baghdad. Another is of a German officer standing over the body of a dead Indian soldier — posing for the “trophy” photograph.

Morton-Jack, to his credit, does not shy away from recording the cruel face of the colonial ruler and details the coercive methods used to recruit the reluctant tribal Indian. He notes that despite all the talk in London of “fighting the world war in defence of freedom”, the unfortunate experience of the Kuki (Assam) and Marri (Baluchistan) tribesmen — where hundreds were killed by British and Indian officers for resisting recruitment — “revealed that as colonial rulers the British had not changed their ugliest spots of colonial control from pre-1914 days”.

This is a splendid book and the author is to be commended for the manner in which he leavens the diligence of the researcher with the objectivity of the historian.

(C. Uday Bhaskar is Director, Society for Policy Studies, New Delhi. He can be reached at cudaybhaskar@spsindia.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

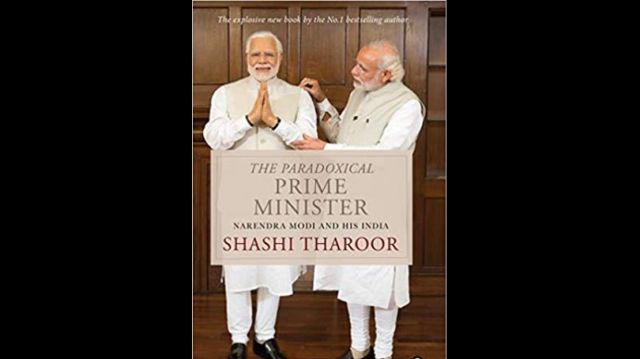

Book: The Paradoxical Prime Minister: Narendra Modi and his India; Author: Shashi Tharoor; Publisher: Aleph Book Company; Pages: 504; Price: Rs 799

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) revels in being in the public eye, and reaps the advantages that come with it. Public scrutiny, however, seems to unsettle it. In a democratic set-up, a citizen who hails and praises a leader also has the right to evaluate and, if necessary, criticise him. Shashi Tharoor, who presented a lengthy argument on (and in) “Why I Am A Hindu”, tackles in his new book a different subject — and has run smack into a controversy with a prickly BJP.

Consider the “scorpion sitting on the Shiva lingam” (icon of Lord Shiva, one of the Hindu Trinity) metaphor, for instance. It appears on page 81 and is used to convey the dilemma of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) — the BJP’s ideological parent — with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The comparison, in the first place, is not Tharoor’s, but that of an unnamed RSS leader, quoted in an article that appeared in 2012, six years ago, in Caravan magazine.

“In his 2012 profile of Mr Modi, the journalist Vinod K. Jose quoted an unnamed RSS leader describing his feelings about the Gujarat supremo with ‘a bitter sigh’: ‘Shivling mein bichhu baitha hai. Na usko haath se utaar sakte ho, na usko joota maar sakte ho’…Try to remove the scorpion, and it will sting you; slap it with a shoe and you will be insulting your own faith. That remains a brilliant summary of the RSS’s dilemma with Narendra Modi,” Tharoor writes in the book.

No sooner were these words uttered by the author at a literary gathering that the BJP cried foul, accusing him of insulting the faith of Hindus. The irony remains that the BJP’s offensive further substantiated Tharoor’s assertions — in this book, and more so those from his last, “Why I Am A Hindu”, where he pointed out that his Hinduism is a lived faith and that the self-proclaimed ‘Hindutva Wadis’ had no business to dictate how one worshiped — or even chose not to worship.

What would one anyways do if a scorpion was to be found sitting on the Shiva lingam? Tharoor does not answer this question but reiterates what the unnamed source had said: That either way there will be a problem. How is this comparison an insult to Hinduism, as Union minister Ravi Shankar Prasad claimed?

But more importantly, the scorpion and not the Shiva lingam is Tharoor’s subject and allegations of hurting the sentiments of Hindus are, at best, attempts to derail the discourse arising from this book. The book is about Modi, and not Hinduism. Criticising Modi is not criticising Hinduism, and those in power would do themselves a great service by reading how a leader from the opposite end of the political spectrum evaluates Modi and his government.

“The Paradoxical Prime Minister” is dedicated to “the People of India who deserve better”. The book is divided into five sections spanning 50 lengthy chapters in about 500 pages. Interestingly, Tharoor’s target is not the post of the Prime Minister, and one can argue that even Modi is not targeted as vehemently as could be expected from a prominent Opposition leader. Remember how the BJP went all out against Manmohan Singh? Tharoor, even in his criticism, is respectful towards the office of the Prime Minister.

What Tharoor does, and succeeds in doing, is show his readers what Modi said and says, and what he and his government did during the four years of their rule so far. The contrasts are presented through a range of sources, not “crack-pot” links hovering all over the internet, but widely accepted, credible sources of information, such as leading newspapers, acclaimed books and magazines.

And Tharoor’s most significant source in “The Paradoxical Prime Minister” is Modi himself. He refers to Modi’s numerous speeches — some emotional, others rhetorical, all of them full of alliterations and punchy slogans — to contend that there is a huge gap between the promise and performance, rhetoric and reality.

It deals with all the core issues that have been at the centre of national discourse during the Modi-led National Democratic Alliance government and ends with a chapter titled “The New India We Seek”, where the author paints a picture of the future that he envisions for the country.

Tharoor is not a neutral observer in the book, as he himself acknowledges in its Introduction, but is, nonetheless, objective. “The Paradoxical Prime Minister” deserves credit for scrutinising the actions of a ruling Prime Minister, focusing on how, according to the author, there is a gap between what he said and what he achieved, and for really laying bare the governance during the past four years. Isn’t this what democracy is all about?

And since a lot is being said in the name of God, one is reminded of Nissim Ezekiel’s “Night of the Scorpion”, a poem set during the night the narrator’s mother was stung by a scorpion. And what happened? “The peasants came like swarms of flies/and buzzed the name of God a hundred times/to paralyse the Evil One”. In the end, rationality survives and superstitions bear no fruit.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in )

—IANS