by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Opinions

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

The ultimate test of a language’s survival is how it is chosen by its users to express their innermost feelings.This yardstick could well explain the case of Urdu, especially when it struck up its enduring partnership with films. And a standard-bearer among those responsible for bringing the ghazal out of courtly soirees to become an eloquent expression for everyman was this failed businessman.

Consider these songs: “Milkar judaa hue to na soya karenge ham/ Ek dusre ki yaad mein roya karenge ham”, “Zindagi mein to sabhi pyar kiya karte hai/Main to mar kar bhi meri jaan tujhe chaahuunga”, “Ye mojeza bhi mohabbat kabhi dikhaaye mujhe…“, or even “Mohe aayi na jag se laaj/main itna zor se naachi aaj/Ke ghunghru toot gaye” or “Chaandi jaisa rang hai tera sone jaise baal/Ik tu hi dhanvan hai gori baaqi sab kangal“.

“Qateel Shifai” penned the lyrics of some of the most heard songs rendered by some of the subcontinent’s best-known voices — Mehdi Hasan, Jagjit Singh, the Sabri Brothers, Pankaj Udhas and more. And he is one of the rare lyricists who has written for both Lollywood and Bollywood.

But the path of Mohammad Aurangzeb Khan (1919-2001) to become “Qateel” was scarcely obvious or smooth, given that there was no tradition of poetry in his family; nor for that matter was Urdu his mother tongue (he was actually a speaker of Hindko, the western Punjabi dialect prevalent across a huge swathe of highland Punjab and stretching into both present Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Kashmir).

Born in a businessman’s family in Haripur in Hazara Division of what was then North-West Frontier Province of British India, he had to stop his studies when 16 as his father died and begin earning for his family. He started his own sporting goods shop in Haripur but as it didn’t prove very successful, Aurangzeb Khan decided to move to Rawalpindi, where he started working for a transport company at the (then) princely sum of Rs 60 per month.

However, his chance to adorn the literary firmament came in 1946, when, out of the blue, he was called to Lahore and offered the post of the assistant editor of a decade-old literary journal “Adab-e-Latif”. His first ghazal was published in Lahore weekly “Star”, edited by Qamar Jalalabadi, the poetic takhallus of Om Prakash Bhandari, who would later become a prominent lyricist in Bollywood.

It was in January 1947, that Qateel — as he had become while adopting the second part of his takhallus from his literary mentor Hakeem Yahya Shifa Khanpuri — was approached by Lahore-based film producer Dewan Sardari Lal to write lyrics for his upcoming film.

This was “Teri Yaad” (1948), starring Dilip Kumar’s brother Nasir Khan, and the first film released in Pakistan. While it is tempting to say that there was no looking back with this, it was not the case yet. For over a decade, it was slogging as an assistant lyricist before he achieved high status in his own right, and it was then we can say that there was no looking back.

Noted for the exquisite simplicity of his love-imbued lyrics, which didn’t remain confined to ghazals, but extended into nazm and geet, Qateel — with “Raat chandni maiin akeli” from “Zehar-e-Ishq” (1956), “Nigahe mila kar badal jaane vaale/Mujhe tujh se koi shikayat nahi hai” from “Mahboob” (1962) or “Dil ke viraane mein ik shamma hai ab tak roshan/Kii parvana magar ab na idhar aayega” from “Naila” (1965) — soon made a name.

But if we are take one particular song as representative of his ability as an incomparable poet of romantic expression at its most sublime, then it has to be “Zindagi mein to sabhi pyaar karte hai…” from film “Azmat” (1973).

With “Apne jazbaat mein nagmat rachane ke liye/Maine dhadkan ki tarah dil mein basaya hai tujhe/Main tasavvur bhi judaai ka bhala kaise karun/Maine qismat ki lakeeron se churaya hai tujhe..” or “Teri har chaap se jalate hain khayaalon mein charagh/Jab bhi tu aaye jagata hua jaadu aaye/Tujhko choo loon to phir ai jaan-e-tamanna mujhko/Der tak apne badan se teri khushbu aaye..”, it deserves a place among the most impressively love lyrics in the Urdu poetical tradition.

But Qateel, who wrote over 2,000 songs in over 200 Pakistani and Indian films, also was lucky, unlike quite a few counterparts on both sides of the border, to be as famous for his “non-filmi” work — be it Jagjit and Chitra Singh in “Milkar juda huye”, declaiming “Aansu chhalak chhalak ke sataayenge raat bhar/moti palak palak mein piroya karenge ham” or Mehdi Hasan warbling “Vo mera dost hai saare jahan ko hai maaloom/Dagah kare vo kisi se to sharm aaye mujhe” and several other classics.

Here he was also not confined to love — the rather ironic “Apne liye ab ek hi raah nijaat hai/Har zulm ko raza-e-khuda kah liya karo” and much more in nearly 20 collections showing his versatility.

And like many others, he could pen an epitaph for himself: “Main apni zaat mein nilaam ho raha hoon ‘Qateel’/Gam-e-hayaat se kah do khareed laye mujhe”. His fear, happily, was misplaced.

(Vikas Datta is an Associate Editor at IANS. The views expressed are personal. He can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Opinions

For representational purpose only

By Vikas Datta,

We may be familiar with the literary concept of ‘poetic justice’, though in this modern technological and globalised age, we are more liable to call it ‘laser-guided karma’. But as the original term suggests, we desire not only justice but justice that happens in a “poetic” manner. Does the poetic form of literature treat advice the same way?

Poets will undoubtedly agree, but so do others too. While Samuel Taylor Coleridge held: “No man was ever yet a great poet without being at the same time a profound philosopher. For poetry is the blossom and the fragrance of all human knowledge, human thoughts, human passions, emotions, language”, an iconic US President also stressed its importance beyond literature.

“When power leads man towards arrogance, poetry reminds him of his limitations. When power narrows the areas of man’s concern, poetry reminds him of the richness and diversity of his existence. When power corrupts, poetry cleanses…” said John F. Kennedy at Massachusetts’ Amherst College, barely a month before his assassination.

But while lessons from “wisdom married to immortal verse”, as Wordsworth termed poetry, abound in Western literature, does our poetic tradition, especially of the courtly and polished Urdu, have similar enlightening and edifying insights into life?

Definitely, as some couplets from its greatest masters show. In these, we can find everything from the fundamental tenet and purpose of religions, the making of India and its composite ‘ganga-jamuni’ culture, the price of existence, the importance (or lack thereof) of the individual, how to appraise fellow humans and what celestial portents indicate.

Though a chronological approach may not be feasible, let’s begin with the earliest of them, the first well-known poet of Urdu, for Mir Taqi ‘Mir’ touches on a subject that has been extremely divisive but he very simply and extremely tellingly brings out its fundamental similarity: “Us ke farogh-e-husn se jhamke hai sab mein noor/Sham-e-haram ho ya ho diya Somnath ka“.

And in the next century, Syed Akbar Hasan Rizvi ‘Akbar Allahabadi’ sought to remind custodians of both of their right (hidden) place in a modern, multi-confessional nation: “Agar mazhab khalal-andaz hai mulki maqasid mein/To shaikh-o-barhaman pinhan rahen dair-o-masajid mein“.

On the other hand, the making of India, with its openness to all kinds of people, is as simply but eloquently explained by Raghupati Sahay “Firaq Gorakhpuri’ in: “Sar-zameen-e-Hind par aqwaam-e-alam ke ‘Firaq’/Qafile baste gaye Hindustan banta gaya“.

All these sentiments however can be better understood and practised once we imbue life’s proper lessons. And here we need those which speak to us as individuals, and there are plenty.

First of all, we must learn to live on reason, not blind faith for Faiz Ahmed ‘Faiz’ noted: “Dast-e-falak mein gardish-e-taqdeer to nahi/Dast-e-falak mein gardish-e-ayyam hi to hai” (or, in simpler terms, the sky doesn’t show fate, but the promise of a new day).

How much importance should we pay our life, is angrily answered by Shaukat Ali Khan ‘Fani Badayuni’, who perhaps taking a cue from Omar Khayyam’s “… Make Game of that which makes as much of Thee” (quatrain XLV, Fitzgerald’s first translation), says: “Zindagi meri bala jaane, mehngi hai ya sasti hai/Muft mile to maut na lun, hasti ki kya hasti hai“.

We must also not look for continuous, unalloyed happiness in it as a matter of right for Mirza Asadullah Khan ‘Ghalib’, in one of his greatest ghazals, tells us: “Qaid-e-hayat o band-e-gham asl mein dono ek hain/Maut se pahle aadmi gham se najat paaye kyun“, or for that matter, think too much of our importance in it: “Ghalib-e-khasta ke baghair kaun se kaam band hai/Roiye zaar zaar kya kijiye haaye haaye kyun“.

But if we had to look for the most useful lesson of umanity, we couldn’t do better that look at the poetry of a monarch, who was himself the monarch of poetry, the unfortunate Bahadur Shah ‘Zafar’, the last of Mughals, who said: “Na thi haal ki jab hamen apni khabar rahe dekhte auron ke aib-o-hunar/Padi apni buraiyon par jo nazar to nigaah mein koi bura na raha“.

He also gave his standard to judge his fellow humans: “Zafar aadmi us ko na janiyega vo ho kaisa hi sahab-e-fahm-o-zaka/Jise aish mein yaad-e-Khuda na rahi jise taish mein khauf-e-Khuda na raha“.

And while we could end with him, his ustad Sheikh Mohammad Ibrahim ‘Zauq’ deserves this honour. And he also has some good advice: “Behtar to hai yehi ki na duniya se dil lage/Par kya karen jo kaam na bedillagi chale“, or even “Duniya ne kis ka raah-e-fana mein diya hai saath/Tum bhi chale chalo yunhi jab tak chali chale“.

That is the best cue to end.

(Vikas Datta is an Associate Editor at IANS. The views expressed are personal. He can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Opinions

By Akanki Sharma, New Delhi, (IANS): In today’s digital era where technology has almost swamped art in all its forms, has Urdu literature once famous for poetry — especially the verse forms of the ghazal and nazm — lost its charm too?

By Akanki Sharma, New Delhi, (IANS): In today’s digital era where technology has almost swamped art in all its forms, has Urdu literature once famous for poetry — especially the verse forms of the ghazal and nazm — lost its charm too?

For centuries, the concept of ‘Mushaira’ — an event called mehfil where poets gather to recite their poems — has been ruling the hearts of people.

With Amir Khusro who started writing Urdu poetry in the 13th century, the trend of ghazal and shaayari began. Years later, several renowned poets like Bahadur Shah Zafar, Mirza Asadullah Beg Khan (Ghalib), Mir Taqi Mir and Faiz Ahmed Faiz, among others, brought the essence of Urdu poetry and its recitation at Mushairas into limelight.

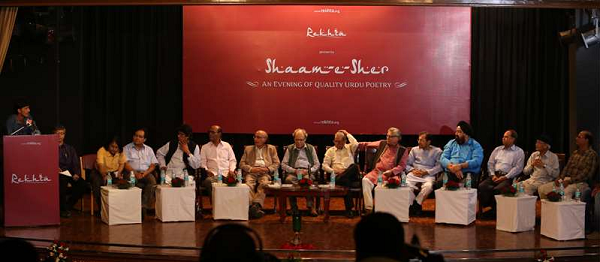

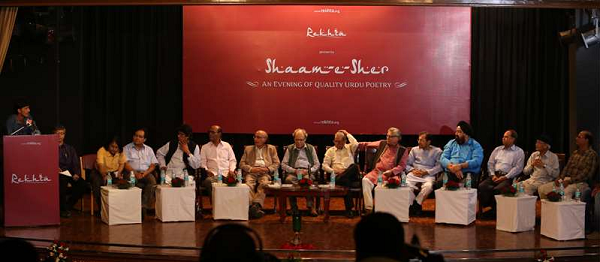

Now ‘Rekhta’ Foundation — one of the world’s largest websites for Urdu poetry and literature — is working to restore ‘Mushaira’ to its true form.

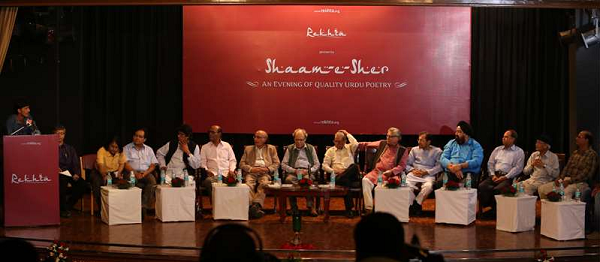

Established in 2013, Rekhta recently organised ‘Shaam-e-Sher,’ an event that provided a platform primarily to the budding poets who are fond of writing Urdu poetry.

Veteran poet Shamim Hanafi, 77, who is also a literary critique and playwright, graced the event, which was jam-packed with young Urdu admirers and which came alive with young poets’ shers and ghazals.

“The audience at Shaam-e-Sher mainly comprised people aged between 18 and 30, a majority of them from non-Urdu background. This shows that Urdu has not lost its flavour and is gaining good acceptance and appreciation amongst the youth,” Aparna Pande of Rekhta told IANS.

It was indeed surprising to witness a huge number of youngsters attending a Mushaira in a Candy Crush and FarmVille-dominated era. The poets who recited their poetry in the mehfil were Parkhar Malviya Kanha and Vipul Kumar, both aged 24, Salim Saleem (31), Vikas Rana and Subhan Asad (34), Manoj Azhar (38), Azhar Iqbal (39), Musavvir Rahman (45), and Shakeel Jamali (58).

Most of the ghazals recited highlighted the theme of love and romance, along with the heartbreaks which have become quite usual with youth these days.

Subhan Asad recited “Do ghadi ko paas aaya tha koi, dil pe barson hukmraani kar gaya. Jisse main eemaan le aaya tha asad, mujhse wahi beyimaani kar gaya. (Someone came close to me for a few moments and ruled my heart forever; The one who taught me honesty also deceived me).”

Similarly, the lines from Azhar Iqbal touched many hearts, “Tumhaare aane ki ummeed bar nahin aati, main raakh hone laga hoon diye jalaate huye (There is no hope that you will come, By lighting these lamps I am turning myself into ashes).”

“The tradition of mushairas is seeing a significant growth, especially in cities like Delhi and Lucknow. People are being more and more engaged in poetry and, by means of that, into themselves,” Vipul Kumar told IANS in an email interview.

A few lines from him: “Is baar usse jung raunat ki thi so hum, apni anaa ke ho gaye uske nahin huye (This time the battle with her was of aggression, so instead of her I embraced my ego).”

Huge applause, whistling and hooting, besides the loud ‘waah-waah’ and ‘mashallah’, filled every heart with enthusiasm. Moreover, not knowing Urdu was not at all a barrier for these young listeners. They were present just to enjoy the sweetness and politeness that the language possesses.

“Urdu is special because of its enriched vocabulary and respectful tone, i.e., tameez and lehza is what makes me fall for it,” said 23-year old Chhavi Tyagi, who has a fondness for ghazals.

That apart, amid today’s restless routines, Urdu shaayari or ghazal also provide people a chance to pause, think, introspect, observe and learn. The words offer solace to the soul.

“With the help of Urdu, one can bare their souls creatively to the world. It is royal, expressive, creative and mesmerising. Its charisma comprises the power to make one fall in love with anything existing in this world,” said 27-year old Romiya Das, who is a regular follower of Rekhta.

Vipul Kumar felt that Urdu is a language of grace, elegance and polish. It has come across some of the genius minds of literature who not only used the language well but also provided the essentials to grow and keep the language delightful for generations to come.

Addressing the gathering, Shamim Hanafi said: “I have been attending and reciting ghazals at Mushairas for ages, but there was hardly any involvement of the youth in those days. However, seeing these young Urdu admirers brings the faith that Urdu literature is going to reign in the years to come.”