by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books, Politics

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

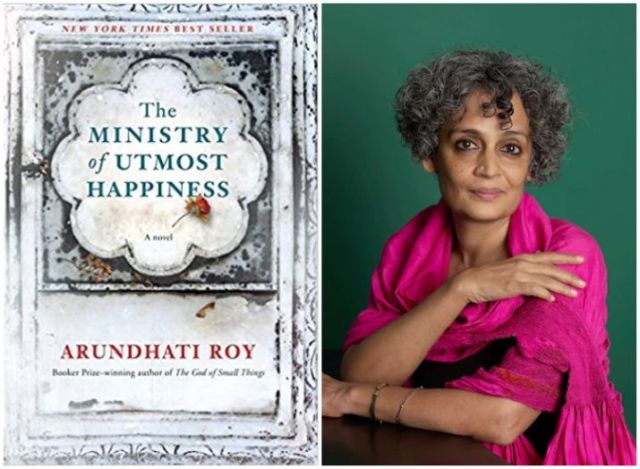

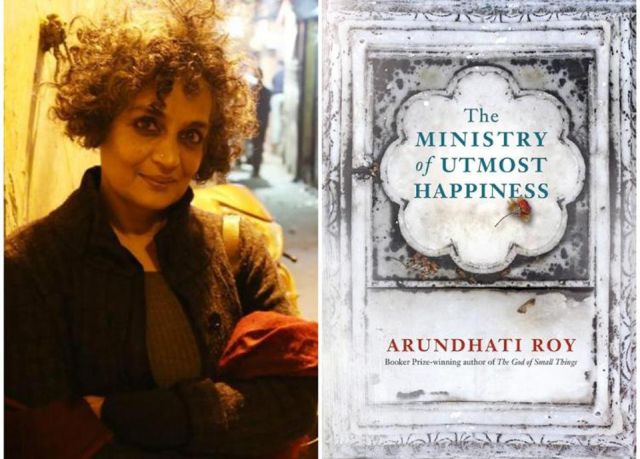

New Delhi : Booker winning novelist Arundhati Roy’s second novel “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness” — written after a hiatus of two decades — is the universe, she says, imagined in many languages which like its characters have no choice but to co-exist. The longing to come home after the companionship it built in 49 languages will see its fulfilment as the Hindi and Urdu editions of the novel — the two closest to its characters as well as the novelist — will release on February 2.

Speaking to IANS ahead of the scheduled launch, the writer extraordinaire said that her novel is structured in a manner that layers after layers have to be peeled to reach to the bottom truth.

“But is there a truth at all?” she asks, maintaining that only fiction can narrate the complexities of our times and that as a novelist, she was also exploring how the written word can give expression to the “strange psychosis” that is happening all around us. It was a novel in progress for about two decades but Roy says she had reached a point when it just needed to flow.

Roy said that she, as a novelist, doesn’t believe in making it “all too easy” for the reader. She toys with her protagonists in the novel, engages in a constant process of exerting and releasing control over their thoughts, actions as well as words — all in a fictional narrative — and suddenly drops it all after taking the reader to a high-point.

She explains that “The Ministry” is a bit like a third-world city, a metropolis submerged under water, and one is only “swimming with the fish” while reading it superficially. “You cannot get through it in one go,” she contends, before pointing out that there are plenty of secret trails and underlying comparisons that are in play in her novel.

You read it once and you are swimming with the fish on top, and then you read it again and you are with the bottom feeders but cannot get through it in one go, she asserts.

At the same time, Roy is mindful that it is written in many tongues and yet no tongue is akin to all. They have their individual characteristics; similarities and dissimilarities with each other, but when placed together in the narrative of a novel, the languages, like its characters, have no option but to co-exist.

Translation for them, she says, is “not a high-end literary art performed by sophisticated polyglots” but it is a part of their “daily life”. She said translation was the primary act that led to the creation of “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness” because the novel is all the time translating, and its adventures with translation is not only limited to languages but also to interpretations and things said, or unsaid between the lines.

Roy, according to Rajkamal Prakashan, who is publishing both the Hindi and Urdu editions of the book, has played an active role in the process of its translation and has spent lengthy hours with the respective translators Manglesh Dabral and Arjumand Ara — both highly revered and masters at the art in respective languages.

She said that the translated works remain faithful to the original text and is translated with a keen attention to the reading experience that the novel presents in its original avatar. The process was not easy as the distinct difference between the literal language and the local street language that some of her characters speak became evident in the first few days of the process.

There were also many words in the original text for which a suitable word wasn’t around in the language it was being translated into.

It was a process of “negotiations”, not “contradictions” and a “protocol” was developed between the writer and the translator(s) so that “The Ministry” retained its original bliss.

The Hindi edition of the novel is titled “Aapar Khushi Ka Gharana” and the Urdu “Bepanah Shadmani Ki Mumlikat”, which will both be launched at India International Centre here.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

(2017 In Retrospect)

(2017 In Retrospect)

By Saket Suman,

New Delhi : A novel that takes its readers into the abyss of poverty and patriarchy, thereby narrating the sordid uses of power and the agony it unleashes; a dystopian satire that draws a telling portrait of our times; and finally an international bestseller from India weaves together a writer’s experiences as a social and environmental activist — all of this in fiction.

Two years ago, there was a spontaneous protest by leading Indian writers who returned their Sahitya Akademi awards in the wake of what they called a growing climate of intolerance and a threat to free speech in the country. Later, these writers were dubbed as those with “vested interests”, seeking “cheap publicity” at a time when their books had “stopped selling”. Those opposed to them pointed out that, as writers, the ideal way to put their perspectives before the public was through their writings — and few could disagree with this fundamental point.

Cut to the present: The year 2017 witnessed the release of at least three powerful novels, along with two short story anthologies, all of which use the medium of art and fiction to reflect the burden of society.

Leading the charge with huge publicity and global media attention was the return of writer-activist Arundhati Roy with her novel “The Ministry of Utmost Happiness”. The novel came after a hiatus of two long decades, during which Roy was actively involved in a number of social and environmental campaigns — a lot of which is reflected in the offering. From Kashmir to Maoists and transgenders to crony capitalism, it is an inward contemplation of a master storyteller on the times and surroundings she is living in.

“I speak as a reader and a publisher when I say that I turn to fiction, as much as to non-fiction, when I seek to make sense of our times, or any time that has gone past us. ‘The Ministry of Utmost Happiness’ is a stellar example of the sheer humanity of the art of the novel. What such a book does is stand up for integrity: It shows us both searing beauty and the fearsome ugliness. Arundhati Roy’s book is an empathetic, hopeful and fiercely idealistic response to the epic tale of Independent India. What more can one ask of a great Indian novel,” Meru Gokhale, Editor-in-Chief, Literary Publishing, of Penguin Random House India, asked while speaking to IANS.

Soon after Roy’s novel came “When the Moon Shines By Day” by Nayantara Sahgal, a member of the Nehru-Gandhi family and a noted writer who spearheaded the “award wapsi” campaign in 2015. The moon obviously does not shine by day nor does the sun shine by night. “Something is wrong if one is forced to agree with such propositions, or be punished for refusing to agree,” Sahgal said, pointing to the larger narrative that she presents in her novel.

Thus, a character finds her father’s books on medieval history disappearing from bookstores and libraries. Her young domestic help, Abdul, discovers that it is safer to be called Morari Lal on the street, but there is no such protection from vigilante fury for his Dalit friend Suraj. Kamlesh, a diplomat and writer, comes up against official wrath for his anti-war views.

And finally, the year closed with the recent release of Kiran Nagarkar’s “Jasoda”, a commentary on society narrated as fiction. The readers question the protagonist Jasoda, seeking to understand whether she is a mother, murderer or saint?

“You could characterise ‘Jasoda’ as a novel that explores the incidence of female infanticide, its causes and its consequences in Indian society, particularly in the hinterland; or a novel that bridges the urban-rural divide through the theme of migration, a live issue for our times; or a novel that depicts the generation gap between the acquiescent pre-liberalisation generation and the ambitious, confident post-liberalisation generation; or a novel that shows how power tends to be all-consuming, and yet how vulnerable the votaries of power eventually are; or a novel that paints the inequities of gender disparity and discrimination in horrifying, poignant ways,” Udayan Mitra, Publisher, Literary, HarperCollins India, told IANS.

” ‘Jasoda’ is all of this and more; for it is above and beyond everything a Kiran Nagarkar novel, written in his inimitable style and marked by his unique perceptions; it captures and transcends reality. Perhaps the most important thing to remember about the book is that the central character is a woman, she is a mother, and her name is Jasoda — a name everyone familiar with mythology knows. What the book is ultimately about, for me, is how myth and reality are at cross-purposes in today’s India,” he added.

Above and beyond these names are “When Danniel Comes to Judgement” by Keki Daruwalla and “Up Country Tales” by Mark Tully — both short story anthologies — bringing many societal issues to the fore. The biggest achievement of these books lies in the fact that they have transported their settings to the ground realities of the times we are living in, moved away from an elitist urbanscape (the current trend) and, in doing so, they have only rekindled the rich legacy of the likes of Raja Rao, Mulk Raj Anand and R.K. Narayan, who gave expression to traditional cultural ethos of India and its ground realities in their writing.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS