‘Spirituality gave way to sensuality in Rajasthani miniature paintings’ (Book Review)

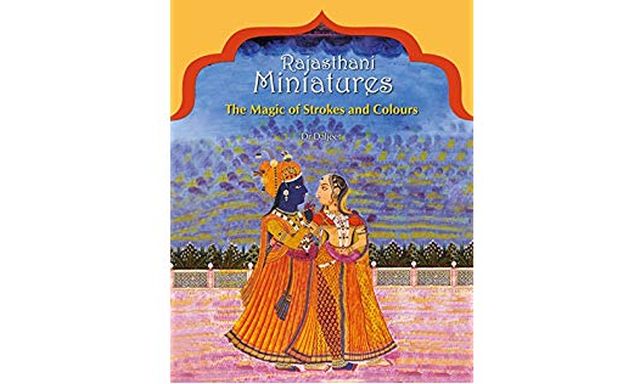

Title: Rajasthani Miniatures: The Magic of Strokes and Colours; Author: Dr Daljeet; Publisher: Niyogi Books; Pages: 392; Price: Rs 4000

During the 1600s, the spiritual unity reflected in Rajasthani miniature paintings began giving way to a more popular trend — sensualism; and a century later, sensualism, or rather eroticism, was the focal point of both court life and court art, says art historian-archaeologist Dr Daljeet in her new book “Rajasthani Miniatures: The Magic of Strokes and Colours”, which she says is an outcome of her study focusing on “what defined Rajasthan in its totality”.

The “lila” between Radha and Krishna was an amalgamation of both romantic and spiritual for the Rajsthani artist, says the former curator and head of the Department of Painting in Delhi’s National Museum.

“Though the hero of Bhakti love poetry was Krishna, paintings depicting him in love scenes gained popularity from the 18th century, and slowly this type of depiction got more patronage from kings,” Daljeet told IANS.

This, the author explains in the book, allowed them “enormous opportunity for portraying various romantic moods and situations, even sensuous and erotic, and elevate at the same time the temporal to the transcendental, the mundane to the spiritual, by revealing the divine dimensions of their ‘lila'”.

“The Rajasthani painter saw hardly any contradiction in combining romance with religion, or the mundane with the transcendental.”

A primer on Rajasthani art, the volume elaborates upon the stylistic sources, mediums, styles, colours and significant themes of the paintings.

It also delves into the major schools of Rajasthani paintings — Mewar, Bikaner, Jodhpur, Nagaur, Jaipur, Alwar, Bundi, Kotah, Kishangarh and Nathdwara — according the paintings chronology and provenance.

She argues that each painting can be connected to a stylistic distinction practised at different ruling seats or even under different patrons. Nature, the author says, held great value for Rajasthani artists, for the simple reason that flora is scarce in Rajasthan.

“With a large part of its land a desert, the people of this western part of India had a special passion for nature, which is reflected in their paintings across centuries,” the introduction says.

“Surya, the sun god; Chandra, the moon god; Vayu, the wind god; and river goddesses Ganga and Yamuna are regular deities of the Brahmanical pantheon. In Rajasthani miniatures, their presence is largely symbolic and motif-based,” she writes in the book.

Peppered with information about the history of both art and Rajasthan, the book does not preach only to the converted, but painstakingly illustrates a larger context within which Rajasthani miniatures are placed and can be understood.

Despite an evident formal similarity, what distinguishes Rajasthani miniatures from their Mughal, Deccani, Central Indian or Pahari counterparts is their spiritual unity endowed by the culture of the land, Daljeet contends in the book.

The book, through a detailed narrative and exquisite photographs, allows a glimpse into the Rajasthani art that has spanned several millennia.

Truly, the book is a magical journey of strokes and colours.

(Siddhi Jain can be contacted at siddhi.j@ians.in)

—IANS