by admin | May 25, 2021 | Media, Opinions

By Saeed Naqvi,

By Saeed Naqvi,

These are such desperate times for journalism that S. Nihal Singh’s departure at 89 triggers memories about a phase in the profession that dreams are made of.

My personal journalistic trajectory trailed his rather closely. He was The Statesman’s Special Correspondent in Singapore when I entered the portals of that once great newspaper as a cub reporter.

I was, in fact, following Nihal’s footsteps because this was how he entered the profession a decade earlier — as a cub reporter. There were no schools of journalism then, but we received training of exactly the thoroughness which our respective letters of appointment had promised: “We do not guarantee you employment at the end of the six-month training period, but the training you will have received here will enable you to find work elsewhere.”

It remained something of a puzzle why the pocket money Nihal was offered during the training period was infinitely higher than mine, which was a meagre Rs 300 per month.

Like most of us who entered the profession after him, Nihal covered New Delhi courts, Tis Hazari courts, Municipal Corporation, Delhi State Assembly, Police Commissioner, Chief Minister. The drill of dwelling on nodal points of governance and power, moving upwards in measured step, imparted to the journalist that most precious of attitudes: An indifference to power, an ability not to be overawed.

As the profession expanded, behavioural contrasts magnified. Untrained entrants at senior levels, who had romanticised political power from a distance, became unsteady on their feet because they found corridors of power too heady. A sense of balance was a frequent casualty.

This is where Nihal could not go wrong. In 1982, when the nation was convulsed by the Meenakshipuram conversions, Nihal, then Editor-in-Chief of the Indian Express, sent a teleprinter message to me in Madras, where I was then posted as editor of five southern editions: “Urgently need 700 words on Meenakshipuram.”

I put on my ultra-balanced hat and churned out the required wordage. It was a typical “while on the one hand” but “on the other” piece. Muslims shouldn’t be up to these tricks and Hindus shouldn’t get too excited. I mentioned “structural violence” in the Hindu social order: This was sacriledge and Nihal let it pass. Unaware of the gathering storm, he thanked me for having responded promptly.

What followed took him and me by surprise. We were both completely out of touch with the strength of feelings on the issue. Indeed, a certain indifference to religion which a whole generation cultivated as Nehruvian secularism was being jettisoned and we found ourselves flat-footed.

After a brilliant career with the IAS and having established himself as a scholar of the Indus Valley script, Iravatham Mahadevan had taken up a job as Executive Manager of the Indian Express’s southern editions. After reading my edit, he came charging to my room in a state of high agitation. “How could you have done it?” He looked at me in a daze, blabbering like someone in a motor accident. “How could you have done it?” I learnt later he was from the RSS, shakhas et al. I commend to the RSS to keep more Mahadevans in its stable. He was exceptionally erudite on subjects of his choice.

In the Express compound, in Hick’s bungalow, Ramnath Goenka was bringing the ceiling down: “Hindu Kahan Javey?” (Where should the Hindus go?) “Tum to Makkay chale jaao; Hindu kahan javey?” (You can go to Mecca, but where should the Hindu go?)

He commandeered his Chartered Accountant, S. Gurumurthy, a senior RSS functionary, to write a rejoinder to my editorial. My “balanced” approach to Meenakshipuram, it transpired, was misplaced.

It was now Nihal’s turn to face the music. The piece, authored by Gurumurthy, arrived at his desk in New Delhi. His job as Editor was on the line. What should he do? But Nihal did what he had learnt in The Statesman. In a newspaper, the prerogative for taking editorial decision rests with the editor. He consigned the article to the waste paper basket. Ramnath Goenka too was a larger than life publisher. He allowed his Editor’s line to prevail. But separation was clearly on the cards; they belonged to different cultures.

So did S. Mulgaonkar “apparently” belong to another culture, but he was both a craftier man and a finer writer. In the projection of his image, Mulgaonkar was exactly Nihal’s opposite. Never having been to school, Mulgaonkar cultivated all the airs of English aristocracy. He was adept at bridge, horse racing, angling, and, believe it or not, keeping Oxford and Cambridge cricket scores. He was a gourmet cook, a fad for which he cultivated junior French diplomats as sources for herbs and white wine. All of this impressed the Marwari in Ramnath Goenka. Once an editor, devoted to the amber stuff, looked at his watch and dropped an obvious hint: “I suppose I will not get a drink here.” Pat came the reply from Goenka, “I keep, but only for English people.”

Nihal had no aristocratic pretenses of a Mulgaonkar. He was content with his buffalo undercut, marinated in garlic and pepper, roast potatoes and Dujon mustard on the side. He called it beef fillet. The Dujon, rather than English mustard, was in deference to his warm hearted Dutch wife, Ge. He had first come to know her when she was a young KLM hostess. I remember him flaunt his European affiliation before friends in London: “I prefer the continent,” he would say with a sort of flat, ineffective pomp.

His understanding of politics and International affairs was uncomplicated. He made up in clarity what he lacked in deep insight. He was, by habit, a perfect gentleman.

It was a mistake, I believe, for both Pran Chopra and Nihal Singh to be parked respectively in Kolkata as editors of The Statesman. The only Punjabi that Bengal has ever tolerated was K.L. Sehgal in New Theatre cinema. This elicited no more than a smile from Nihal.

(Saeed Naqvi is a commentator on political and diplomatic affairs. The views expressed are personal. He can be reached on saeednaqvi@hotmail.com)

—IANS

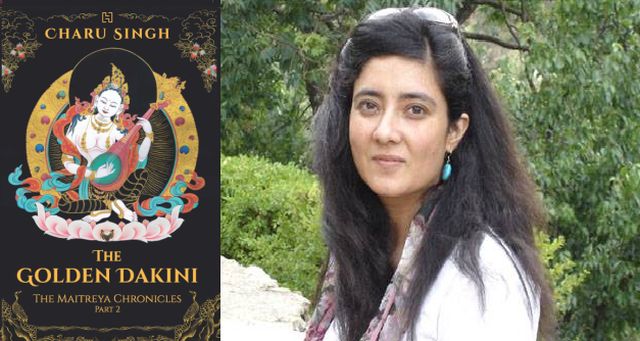

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books, Entrepreneurship, Media, Success Stories, Women Entrepreneur

Charu Singh

By Saket Suman,

New Delhi : She worked as a journalist for Asian Age, Frontline and Tribune, but running behind bylines always seemed like “instant coffee” with no time to pause and appreciate the beauty of things around her. After she quit her full-time job and embarked on a journey of writing, life changed drastically for Charu Singh, whose second book was published in December.

“I wrote a lot of poetry as a young child and also continued with it in my teenage. And then I became a journalist, which, to a large extent, taught me the discipline of writing. But working as a journalist was like instant coffee; one was always looking for bylines and breaking news. I always had this thing in the back of my mind that I want to write something some day.

“Now, when I look back at the journey of writing, it has been much more satisfying. It is self-discovery of sorts, because you are finding new facets about yourself every other day,” Singh told IANS.

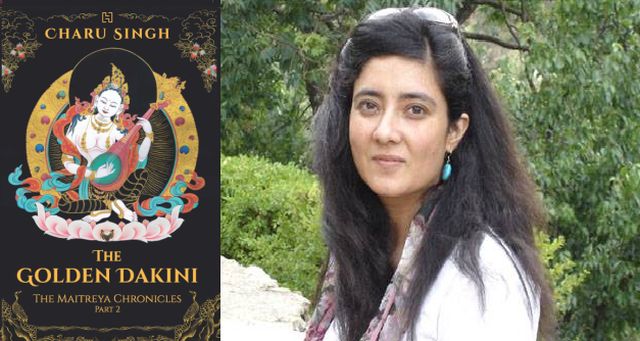

Singh’s first book, “Path of the Swan”, is part of a Buddhist fantasy series that she spent quite a lot of time writing. In December 2017, “The Golden Dakini”, the second book in the series, released and was widely lauded in literary circles.

In these books, Singh said, she has used elements of “Tibetan Buddhism”, especially myths centred around “the Vajrayana system of Buddhism”, which is a part of the larger Mahayana body of Buddhism.

“I have especially used the myth centred around the legendary kingdom of Shambala which is particular to Vajrayana Buddhism and is the subject of much debate and thought among monks and lay practitioners of this arm of Buddhism. In this Buddhist fantasy series I have finished the story with “The Golden Dakini”; so currently the Maitreya chronicles is a set of two books. However, there is the possibility of me doing a third book centred around the Maitreya,” she added.

Singh is not a practising Buddhist and, therefore, her exploration of Buddhism has a lot more significance for both the reader and the writer. Readers, for instance, come across sweeping landscapes in the Northeast and Leh, where majestic monasteries paint the pages of her book. The stories are not told from the perspective of a Buddhist, but from somebody who has attempted to understand the religion and then weave a fictional narrative around it.

For the writer in Singh, it has been a great experience. “The journey of my research and me simply going about learning little nuggets of Buddhism has been a fascinating experience. It opened new windows and horizons for me personally,” she quipped.

“The Golden Dakini” centres around action building up to the birth of the divine child, the Maitreya Buddha. The book begins at Qiang La, and a group of five characters travel across Tibet and make their way to Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim. They stay there for about a week and have meetings with Rimpoche Gyaltsen, who hints at the location of Mt Meru — a mystical, divine mountain mentioned in both Buddhist and Hindu legends.

The task before the group is to locate Mt Meru, which has long been lost from the public eye. As the group follows the trail of clues leading to the mountain, they reach Guwahati in Assam where they reside for some time and look for a Hindu sage who can tell them the path ahead.

A book set in exotic locations, “The Golden Dakini” is both a page-turner and a celebration of the many sublime aspects of Buddhism.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Media, News

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Jaipur : They represent journalism at its most exciting, influential but also lethal. Top journalists who have covered a wide spectrum of issues from the repressive life in North Korea, to brutal Islamist terrorism, to the plight of the Rohingya refugees admit that “frontline” reporting is now undergoing a paradigm shift due to various factors, especially the communications revolution which allows everyone to tell their story without intermediaries.

And equally important is the enhanced powers and techniques available with authorities who only want their version to go out, contended five acclaimed global journalists at a session entitled “The Frontline Club” at the “Jaipur Literature Festival 2018” here on Friday.

Kicking off the discussion with her experiences of reporting from North Korea, South Korean-American writer Suki Kim highlighted the failure of traditional journalism in North Korea in the face of pervasive state propaganda, and lack of access to and for foreign journalists.

This, Kim said, had made her to go undercover in an attempt to bring out the actual position in the world’s most closed and conforming society. This ensured she was the first to have ever covered North Korea through “immersive journalism”, since this was the “only way to bring out stories of generations of people who suffered unimaginable violence that would otherwise be buried in history”.

It was by no means easy – for over a decade she had to store what she managed to find on the smallest USB device and run the risk of prosecution or worse if found out. Kim said that the threats that followed the publication of her account were nothing compared to the fear of living in the country where lies had become “a matter of survival”.

On how frontline journalism has changed after 9/11, Peter Bergen, who is currently CNN’s national security analyst and authored books on the manhunt for Al Qaeda supremo Osama Bin Laden and the “war” that followed the attack on the US – and shows no signs of ending soon, felt that for one, the new patterns of global terrorism have erased the distinction between its domestic and foreign manifestations.

Furthermore, social media has changed the face of terrorism, with terrorist and insurgent organisations “using the most cutting-edge technology as their own effective channel of distribution, no longer depending on mainstream broadcast media interviews”, he said.

On the success of frontline journalism in discovering the truth, he quipped: “We’re in the business of trying to solve puzzles, and most often we don’t solve them: there may be no answers to the lies.”

Adrian Levy, of the Guardian and famous in India for his in-depth works on the Kashmir insurgency, the 26/11 attack and the role of David Coleman Headley, and the long search for Bin Laden and the fate of his family and close adherents between 9/11 and the Abbottabad raid, feels the search for truth involves numerous people and has a positive side too – the privilege of the “intimacy of being welcomed despite being different”.

Recounting his experiences covering the arrival of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, Jeffrey Gettleman, of The New York Times and a Pulitzer winner, said that a journalist’s job is to “take the information from the people in as dignified a way as possible, and then expose the injustice – a parasitic role, but with a higher purpose” in giving a voice to people who have suffered and resisted.

Swiss-born journalist Carlo Pizzati emphasised the need to make these stories “beautiful and meaningful,” so readers could connect to them, whilst remaining faithful to the facts.

Levy also said that this objective is increasingly important in what is the “golden age of investigative fiction”, and also the best and the worst of times to be a journalist.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS