by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

Book: The Paradoxical Prime Minister: Narendra Modi and his India; Author: Shashi Tharoor; Publisher: Aleph Book Company; Pages: 504; Price: Rs 799

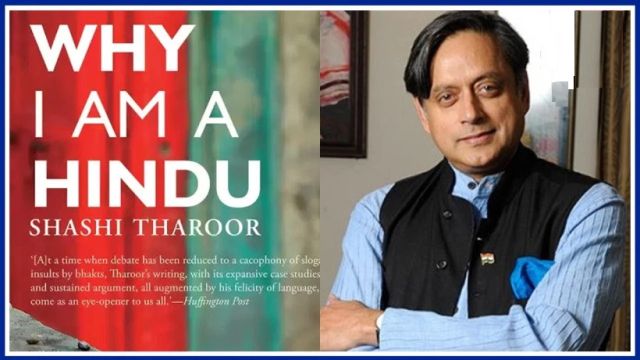

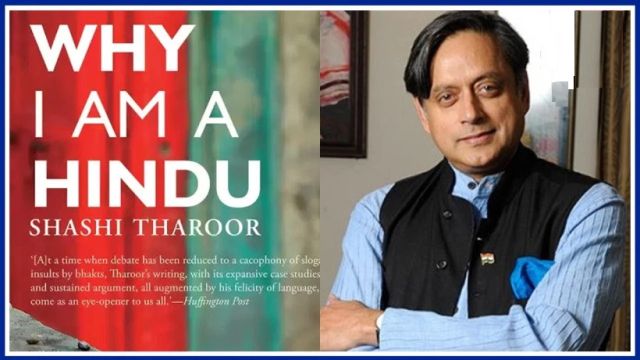

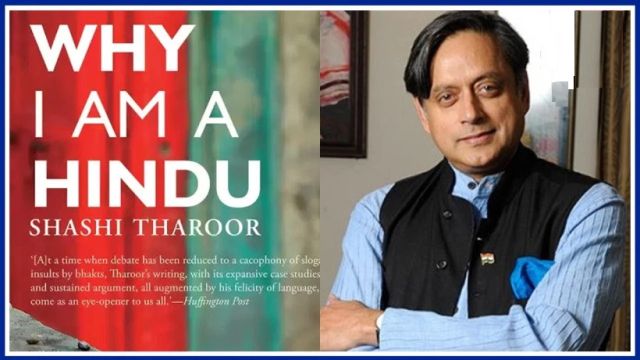

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) revels in being in the public eye, and reaps the advantages that come with it. Public scrutiny, however, seems to unsettle it. In a democratic set-up, a citizen who hails and praises a leader also has the right to evaluate and, if necessary, criticise him. Shashi Tharoor, who presented a lengthy argument on (and in) “Why I Am A Hindu”, tackles in his new book a different subject — and has run smack into a controversy with a prickly BJP.

Consider the “scorpion sitting on the Shiva lingam” (icon of Lord Shiva, one of the Hindu Trinity) metaphor, for instance. It appears on page 81 and is used to convey the dilemma of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) — the BJP’s ideological parent — with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The comparison, in the first place, is not Tharoor’s, but that of an unnamed RSS leader, quoted in an article that appeared in 2012, six years ago, in Caravan magazine.

“In his 2012 profile of Mr Modi, the journalist Vinod K. Jose quoted an unnamed RSS leader describing his feelings about the Gujarat supremo with ‘a bitter sigh’: ‘Shivling mein bichhu baitha hai. Na usko haath se utaar sakte ho, na usko joota maar sakte ho’…Try to remove the scorpion, and it will sting you; slap it with a shoe and you will be insulting your own faith. That remains a brilliant summary of the RSS’s dilemma with Narendra Modi,” Tharoor writes in the book.

No sooner were these words uttered by the author at a literary gathering that the BJP cried foul, accusing him of insulting the faith of Hindus. The irony remains that the BJP’s offensive further substantiated Tharoor’s assertions — in this book, and more so those from his last, “Why I Am A Hindu”, where he pointed out that his Hinduism is a lived faith and that the self-proclaimed ‘Hindutva Wadis’ had no business to dictate how one worshiped — or even chose not to worship.

What would one anyways do if a scorpion was to be found sitting on the Shiva lingam? Tharoor does not answer this question but reiterates what the unnamed source had said: That either way there will be a problem. How is this comparison an insult to Hinduism, as Union minister Ravi Shankar Prasad claimed?

But more importantly, the scorpion and not the Shiva lingam is Tharoor’s subject and allegations of hurting the sentiments of Hindus are, at best, attempts to derail the discourse arising from this book. The book is about Modi, and not Hinduism. Criticising Modi is not criticising Hinduism, and those in power would do themselves a great service by reading how a leader from the opposite end of the political spectrum evaluates Modi and his government.

“The Paradoxical Prime Minister” is dedicated to “the People of India who deserve better”. The book is divided into five sections spanning 50 lengthy chapters in about 500 pages. Interestingly, Tharoor’s target is not the post of the Prime Minister, and one can argue that even Modi is not targeted as vehemently as could be expected from a prominent Opposition leader. Remember how the BJP went all out against Manmohan Singh? Tharoor, even in his criticism, is respectful towards the office of the Prime Minister.

What Tharoor does, and succeeds in doing, is show his readers what Modi said and says, and what he and his government did during the four years of their rule so far. The contrasts are presented through a range of sources, not “crack-pot” links hovering all over the internet, but widely accepted, credible sources of information, such as leading newspapers, acclaimed books and magazines.

And Tharoor’s most significant source in “The Paradoxical Prime Minister” is Modi himself. He refers to Modi’s numerous speeches — some emotional, others rhetorical, all of them full of alliterations and punchy slogans — to contend that there is a huge gap between the promise and performance, rhetoric and reality.

It deals with all the core issues that have been at the centre of national discourse during the Modi-led National Democratic Alliance government and ends with a chapter titled “The New India We Seek”, where the author paints a picture of the future that he envisions for the country.

Tharoor is not a neutral observer in the book, as he himself acknowledges in its Introduction, but is, nonetheless, objective. “The Paradoxical Prime Minister” deserves credit for scrutinising the actions of a ruling Prime Minister, focusing on how, according to the author, there is a gap between what he said and what he achieved, and for really laying bare the governance during the past four years. Isn’t this what democracy is all about?

And since a lot is being said in the name of God, one is reminded of Nissim Ezekiel’s “Night of the Scorpion”, a poem set during the night the narrator’s mother was stung by a scorpion. And what happened? “The peasants came like swarms of flies/and buzzed the name of God a hundred times/to paralyse the Evil One”. In the end, rationality survives and superstitions bear no fruit.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in )

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | News, Politics

By Arul Louis,

By Arul Louis,

New York : Hinduism is a “wonderful” religion suited for the modern era of uncertainty and questioning because it values incertitude, according to Congress MP and author Shashi Tharoor, who also excoriated the politicisation of the faith.

“Hinduism rests on the fact that there is a heck of a lot we don’t know about,” Tharoor said on Thursday during an interactive session at JLF@NewYork, the edition of the Jaipur Literature Festival.

What makes it fit for today’s world, he said “the first is the wonderful fact that in an era of uncertainty, incertitude, you have uniquely a religion that privileges incertitude”.

About creation, the Rig Veda actually says “where the universe comes from, who made all of this heaven and earth, may be He in the heaven knows, may be even He does not know”, he noted.

“A religion that is prepared to question the omniscience of the Creator is to my mind a wonderful faith for a modern or post-modern sensibility.

“On top of that, you have got extraordinary eclecticism” and since no one knows what God looks like one is free to imagine God as one likes in Hinduism, he said.

The Congress Party MP, who is the author of “Why I am a Hindu”, took issue with those who condemn the religion as built on misogyny and discrimination.

About the Laws of Manu, he said, “there is very little evidence as to whether they were observed” and there were many texts that existed.

Of these texts, “I don’t think every Hindu took the advice of the Kama Sutra, either”, he joked.

“For every misogynistic or casteist pronouncements (in Hindu texts) I can give you other equally sanctified texts that preach against casteism,” he said.

He explained that Hinduism “is not a religion of one holy book, but of multiple sacred texts. There’s an awful lot to pick from. What you pick is up to you. If you choose to pick the misogynist or casteist or offensive bits of the religion and say my religion allows me to discriminate against people or to oppress people, it is your fault not the religion’s.”

He made a distinction between religion and social practices that are not based on faith.

Tharoor’s expansive and deep explanation flies in the face of campaigns in the US against Hinduism with claims about caste discrimination and misogyny, including attempts to disrupt the World Hindu Congress earlier this month in Chicago.

Tharoor held out hope for the spirit of tolerance and acceptance to triumph in India.

The spasms of bigotry were a passing phase in India because tolerance and acceptance of the other was “built into the bones” of the Indian people, he said.

“That kind of bigotry that we have seen whipped up in the recent years is essentially a political exercise and to my mind not in any way reflective of the spirit of most of the Indian people,” he said.

“You can’t really change their fundamental nature,” he added.

The “resurgent Hindu nationalism is actually based on a dismaying inferiority complex” of those who feel their “religion has been conquered, subjugated; they feel a humiliation, an ancestral humiliation”, he said.

“Whereas the Hinduism that I have seen, read, grown up with, practiced and being taught is a much more self-confident Hinduism,” he said, conceding that the approaches may be a sign of a north-south divide.

(Arul Louis can be reached at arul.l@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books, News, Politics

New Delhi : Politician and author Shashi Tharoor’s book “Why I Am A Hindu” will be made into a web series with National Award-winning producer Sheetal Talwar as showrunner. The Congress MP will also narrate it.

New Delhi : Politician and author Shashi Tharoor’s book “Why I Am A Hindu” will be made into a web series with National Award-winning producer Sheetal Talwar as showrunner. The Congress MP will also narrate it.

Taking head-on the current misinterpretation and misappropriation of Hinduism, Tharoor’s book is about the history of Hinduism and its core tenets, as well as socio-cultural developments in India that relate to Hinduism and his own religious convictions.

The book is a repudiation of Hindu nationalism, and its rise in Indian society, which relied upon an interpretation of the religion which was markedly different from the one with which he has grown up, practiced and had studied.

On its adaptation, Tharoor said in a statement to IANS: “In any time and era, an adaptation of this book into film would be relevant, but in the current political, social and cultural environment it is imperative that the message of true Hinduism – the Hinduism of acceptance reach the widest audience possible.”

“I am glad that Sheetal and I – who share a similar belief system – are collaborating on this effort,” he added.

Talwar, who will be seen producing in India after nearly 7 years, says when she gave “Why Am I A Hindu” a read, it shook him.

“I was ashamed that as someone whose profession is to voice, I had not raised my voice and done nothing while the inherent integrity of our pluralism was being threatened.

“After ‘Dharm’ and ‘Rann’, it is after years that I have been so excited about a subject. I am glad that I could convince Shashi to not only make this into a web series, but also offer his time as a narrator to the series.”

The series will headline numerous known filmmakers film an episode each. It is set to be made in various Indian languages and will be released in the first quarter of 2019, the statement read.

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By M.R. Narayan Swamy,

By M.R. Narayan Swamy,

Title: Adi Shankaracharya: Hinduism’s Greatest Thinker; Author: Pavan K. Varma; Publisher: Tranquebar Press; Pages: 364; Price: Rs 699

This must be one of the greatest tributes ever paid to Shankaracharya, the quintessential “paramarthachintakh”, who wished to search for the ultimate truths behind the mysteries of the universe. His genius lay in building a complete and original philosophical edifice upon the foundational wisdom of the Upanishads.

A gifted writer, Pavan Varma, diplomat-turned-politician and author of several books including one on Lord Krishna, takes us through Shankara’s short but eventful span of life during which, from having been born in what is present-day Kerala, he made unparalleled contributions to Hindu religion that encompassed the entire country. Hinduism has not seen a thinker of his calibre and one with such indefatigable energy, before or since.

Shankara’s real contribution was to cull out a rigorous system of philosophy that was based on the essential thrust of Upanishadic thought but without being constrained by its unstructured presentation and contradictory meanderings.

He was greatly influenced by three basic texts of Hindu philosophy: Upanishads, the Brahma Sutra and the Bhagavad Gita. He wrote extensive and definitive commentaries on each of them. Of course, the importance he gave to the Mother Goddess, in the form of Shakti or Devi, can be traced to his own attachment to his mother whom he left when he set off, at a young age, in search of a guru and higher learning.

Against all odds, Shankara created institutions for the preservation and propagation of Vedantic philosophy. He established “mathas” with the specific aim of creating institutions that would develop and project the Advaita doctrine. He spoke against both caste discriminations and social inequality, at a time when large sections of conservative Hindu opinion thought otherwise.

Shankara was both the absolutist Vedantin, uncompromising in his belief in the non-dual Brahman, and a great synthesiser, willing to assimilate within his theoretical canvas several key elements of other schools of philosophy. He revived and restored Hinduism both as a philosophy and a religion that appealed to its followers.

Varma rightly says that it must have required great courage of conviction as well as deep spiritual and philosophical insight for Shankaracharya to build on the insights of the Upanishads a structure of thought, over a millennium ago, that saw the universe and our own lives within it with a clairvoyance that is being so amazingly endorsed by science today. The irony is that most leading scientists, particularly outside India but also within, have little knowledge of the structure of Shankara’s philosophy and the transparent interface it has with scientific discoveries today.

Shankara wrote hymns in praise of many deities but his personal preference was the worship of the Mother Goddess. The added value of the book is that it has, in English, a great deal of Shankara’s writings. Unfortunately, most Hindus today are often largely uninformed about the remarkable philosophical foundations of their religion. They are, the author points out, deliberately choosing the shell for the great treasure that lies within. This is indeed a rich book.

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Devdutt Pattanaik,

By Devdutt Pattanaik,

The key to understanding Karmic faiths is to look at stories, for it is through stories that the common folk understood their faith.

In Hinduism, we find many stories where God transforms into Goddess, indicating gender fluidity, as also men turning into women and women into men. This reveals a greater comfort with transgender identities. Although there are images of male-male and female-female friendship, one is never sure if this love is platonic, romantic or sexual, leaving them open to interpretations.

Also, many queer themes in stories are metaphors used to communicate complex metaphysical ideas in narrative form. Hinduism reveals a greater comfort with transgender stories. For example, there are stories that describe Lord Vishnu becoming a damsel and Lord Shiva becoming half a woman. However, homosexuality is not a dominant theme in Hindu mythologies.

In contrast, Greek mythologies are replete with stories of homosexual love, where men love men, and women love women. Apollo falls in love with Hyacinthus, while his sister Artemis drives Callisto away when she lets a man make her pregnant. There are also many descriptions of man-boy love found in Greek tales. So while Greek mythology reveals a comfort with queer sexuality (invisible feelings), Hindu mythology reveals a comfort with queer gender (visible body).

This divide is reflected in modern LGBTIQ politics. The West, influenced by Greek mythology, exhibits greater comfort with the homosexual than with the transgender. Whereas India, influenced by Hindu mythology, reveals greater comfort with the transgender than with the homosexual.

Significantly, no Hindu, Buddhist or Jain scripture has tales like that of Sodom and Gomorrah from the Abrahamic tradition, popularly interpreted as being about divine punishment against queer behaviour.

In hermit traditions of the Karmic faiths, sensuality is seen as causing bondage to the sea of materiality and entrapping man in the endless cycle of rebirths. Sex is seen as polluting andonly the celibate man (sanyasi) and the chaste woman (sati) are considered pure and holy. And so an identity based on sexuality draws much criticism. That is why in Vinaya Pitaka, the code of conduct for Buddhist monks, it is explicitly stated that the queer pandaka should not be ordained.

Rules extend to women who dress like men, or do not behave like women, which we can take to mean lesbians. Jain rejection of homosexuality also stems from its preference for the monastic lifestyle. Anti-queer comments on homosexual behaviour in the Manusmriti are more concerned with caste pollution than the sexual act itself. People involved in non-vaginal (ayoni) sex are told to perform purification rites, such as bathing with clothes on or fasting. More severe purification is recommended for heterosexual adultery and rape.

Karmic faiths believe that the living owe their life to their ancestors and so have to repay this debt (pitr-rina) by marrying and producing children. This is a key rite of passage (sanskara). This is a major reason for opposing same-sex relationships, which are seen as essentially sterile and non-procreative. Sikhism states nothing against queer genders or sexuality but values marriage and the householder’s life.

(Devdutt Pattanaik is among India’s leading authors on mythology with over 30 books in print. Extracted from “I am Divine So Are You: How Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and Hinduism Affirm the Dignity of Queer Identities and Sexualities”, introduced by the author and edited by Jerry Johnson. With permission from HarperCollins India)

—IANS