by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By M.R. Narayan Swamy,

By M.R. Narayan Swamy,

Title: Adi Shankaracharya: Hinduism’s Greatest Thinker; Author: Pavan K. Varma; Publisher: Tranquebar Press; Pages: 364; Price: Rs 699

This must be one of the greatest tributes ever paid to Shankaracharya, the quintessential “paramarthachintakh”, who wished to search for the ultimate truths behind the mysteries of the universe. His genius lay in building a complete and original philosophical edifice upon the foundational wisdom of the Upanishads.

A gifted writer, Pavan Varma, diplomat-turned-politician and author of several books including one on Lord Krishna, takes us through Shankara’s short but eventful span of life during which, from having been born in what is present-day Kerala, he made unparalleled contributions to Hindu religion that encompassed the entire country. Hinduism has not seen a thinker of his calibre and one with such indefatigable energy, before or since.

Shankara’s real contribution was to cull out a rigorous system of philosophy that was based on the essential thrust of Upanishadic thought but without being constrained by its unstructured presentation and contradictory meanderings.

He was greatly influenced by three basic texts of Hindu philosophy: Upanishads, the Brahma Sutra and the Bhagavad Gita. He wrote extensive and definitive commentaries on each of them. Of course, the importance he gave to the Mother Goddess, in the form of Shakti or Devi, can be traced to his own attachment to his mother whom he left when he set off, at a young age, in search of a guru and higher learning.

Against all odds, Shankara created institutions for the preservation and propagation of Vedantic philosophy. He established “mathas” with the specific aim of creating institutions that would develop and project the Advaita doctrine. He spoke against both caste discriminations and social inequality, at a time when large sections of conservative Hindu opinion thought otherwise.

Shankara was both the absolutist Vedantin, uncompromising in his belief in the non-dual Brahman, and a great synthesiser, willing to assimilate within his theoretical canvas several key elements of other schools of philosophy. He revived and restored Hinduism both as a philosophy and a religion that appealed to its followers.

Varma rightly says that it must have required great courage of conviction as well as deep spiritual and philosophical insight for Shankaracharya to build on the insights of the Upanishads a structure of thought, over a millennium ago, that saw the universe and our own lives within it with a clairvoyance that is being so amazingly endorsed by science today. The irony is that most leading scientists, particularly outside India but also within, have little knowledge of the structure of Shankara’s philosophy and the transparent interface it has with scientific discoveries today.

Shankara wrote hymns in praise of many deities but his personal preference was the worship of the Mother Goddess. The added value of the book is that it has, in English, a great deal of Shankara’s writings. Unfortunately, most Hindus today are often largely uninformed about the remarkable philosophical foundations of their religion. They are, the author points out, deliberately choosing the shell for the great treasure that lies within. This is indeed a rich book.

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: The Genius Test: Can You Master the World’s Hardest Ideas?; Author: Giles Sparrow; Publisher: Quercus; Pages: 224; Price: Rs 599

The biggest fallacy in our high-tech world is believing that the stunning advances in knowledge — now accessible anytime and everywhere through flashy devices — have left everyone, especially the millennials, well-learned. But could any one of them, just asked, explain the “hard problem” of consciousness, the essence of post-modernism, or how quantum theory relates to the everyday world.

Or from other fields, could they weigh in, without a fast consultation on the internet, on the difference and the purpose of structuralism and semiotics, the potential of nanotechnology or the basic difference between left, right and central political theories?

While most of these issues, spanning pure science to philosophy to politics, and from culture to economy to technology may seem rather academic and only required for those appearing for a civil service examination, these are all subjects on which we may need detailed, valid opinions in an increasingly complex world. For these are matters that cannot be left to the experts.

Acquiring a basic grounding in them may seem a tall order, especially for a generation used to shortcuts, just the bare essential knowledge and a higher predilection for gossip. But this book might be of help.

And then this knowledge may be make you sought-out — probably, argues author Giles Sparrow.

“We’ve all had that experience — nodding along wisely to a conversation about a topic we barely understand, when someone asks for our opinion, and the floor abruptly drops away from under us. Usually, our instinct is to mutter something non-committal or agree with whoever seems to be the smartest person in the group. But what if we could be that person?” he asks.

Towards this goal, Sparrow, who has a two-decade career in publishing that has seen him write books on subjects spanning spaceflight, archaeology and mythology, and editing bestsellers by top authors on fields ranging from quantum physics to economics to evolution, makes use of his experience to help create spread knowledge.

This, he aims to achieve by presenting the basic essentials of a huge range of topics across the fields of life itself — from the debate about its origins and development to particularly human traits of consciousness and language, philosophy, the mind, the arts, politics and economics, mathematics, physics and finally cosmology.

While the issues he covers begin from the “tricky”, say the nurture vs nature problem, the history of literature, the contemporary vexed matter of digital politics, they rise up to the “tough” ones — genetic engineering, nature of reality, and concept of infinity, and then to the “formidable”, encompassing good and evil, post-capitalism, black holes and multiverses and the like.

Finally, there are the seven “mind-blowing” issues, that can change how we look at “certainties” — ranging from free will and God to Fermat’s Last Theorem and the Theories of Everything.

But in all the issues Sparrow covers, arranged thematically, the treatment is similar. Each entry has a relevant quote, a basic outline of the issue, five “true or false” questions to gauge your understanding of the topic, before “10 Things a Genius Knows”, offering a comprehensive but lucid overview of the topic, including both its central ideas and historical development.

But that is not all. You also get a smattering of opinions, facts and interesting titbits to show your knowledge is not just based on reading the encyclopaedia, and for all those wanting only the bare-bones essential, a concise but incisive summary not exceeding two sentences.

This is not merely intended as a crib sheet for those who belatedly have come to the realisation that they should know something about the great issues of the day. Sparrow stresses that it won’t make you a bona fide genius (though a “better bluffer at parties”), but may “even change the way you look at the world and reveal a previously undiscovered intellectual ability or interest”.

And in that way, may lie not only your salvation, but of the world. So stop looking at, tapping, scrolling your smartphone and read this.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

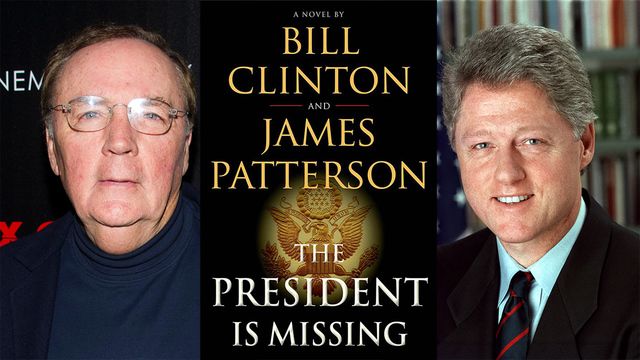

Title: The President is Missing; Author: Bill Clinton & James Patterson; Publisher: Century/Penguin Random House; Pages: 528; Price: Rs 599

The world’s most powerful nation faces a terrible terrorist threat that can send it reeling into chaos and violent anarchy. But can the US President be relied on to tackle this dire peril, given he is not at his peak physically, had questionable “links” with a most wanted terrorist, and then cannot be located at all.

As ominous presentiments of the looming danger are reported from across the country and elsewhere, close allies are wracked by instability and old adversaries close in to take advantage. Meanwhile, President Jonathon Lincoln Duncan is not helped by revelations that he not only talked to the terrorist but also committed American forces to save him from an attack — and the threat of impeachment is a very real possiblity.

But what has the President actually done — and is now doing — about the threat? And how does a group of assassins on his trail know all about his location to target him, leading to firefights on the streets of Washington?

With the clock ticking away to the unleashing of a potent, stealthy and unstoppable computer virus that can irredeemably cripple the cyber infrastructure on which the entire American society, economy and security rests, Duncan has to draw on some unlikely help to fulfill his oath to protect and preserve his country. But does he know who his friends and foes are?

The ingredients are all there for a story that may well be ripped from the headlines, and in the hands of former US President Bill Clinton, with his experience of the compulsions and intrigues of top political power, and best-selling author James Patterson, skilled in spell-binding storytelling, it seems to make for an unprecedented thriller.

But does it?

Not, exactly. For what can be a thrilling account of the nuances of facing the ultimate threat for any technologically advanced nation somehow never manages to quite get off the ground, for many reasons.

First of all, the title is misleading, for the President is never missing. Some close aides and his dedicated Secret Service detail do know where he is — as do his prospective assassins; and most of the story’s narration is from the point of view of Duncan himself, which rather robs the surprise element, since he is not too open with us.

This narrative style also does another disservice to the whole plot, as diligent readers will eventually discover.

The character of the President himself doesn’t hold much surprise — he is “fifty years old and rusty”, has “rugged good looks and a sharp sense of humour”, met his more intelligent wife in law school, and has an equally intelligent daughter, studying at the Sorbonne.

On the other hand, he has been a war hero too — from the first Gulf War — Governor of North Carolina, and, a bit confusingly, is a widower (psychoanalysts, take note) and came to power after some of his formidable rivals committed self-goals. And then, too many women in his administration — Vice President, Chief of Staff, Deputy Chief of Staff, FBI Director — which rather strains incredulity.

Then, behind the plot to “reboot the world” is Suliman Cindoruk, “the most dangerous and prolific cyberterrorist in the world”. He is “Turkish-born” but “not Muslim” and yet leads an organisation known as the Sons of Jihad — whose members include Slav Christians.

His prime weapon, the assassin known as Bach (from her favourite music while operating) is rather incongruous and a bit of a fanservice (she prefers to look sexy to be inconspicuous — “the tall, leggy, busty redhead, hiding in plain sight”).

Were all these not enough, Duncan’s plan to combat the virus — involving three heads of state/government, along with their experts — and his own contribution is frankly unbelievable as are the “revelations” about the real backers of the plot. And then Duncan’s final speech is Clinton’s unfinished agenda.

What works better are the moral dilemmas about innocent, collateral damage the President must face and ponder in real time while deciding anti-terror operations, the limitations of power, and the resentments of those in positions below what they aspire too/feel entitled too.

Good for a read — once, with not much expectations; overall, it is a disappointment from such a potentially promising pair of collaborators. Maybe Hillary Clinton should try something.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

Book: Too Many Men Too Few Women; Edited by: Ravinder Kaur; Publisher: Orient Blackswan; Pages: 340; Price: Rs 925

Much of the scholarly work on adverse sex ratios or gender imbalance until now has primarily focussed on the identification, patterns and causes of skewed sex ratios, and very little on their consequences. This offering, on the contrary, focuses on their social consequences in China and India — two of the world’s most populous countries — by presenting an empirical work and ethnographic accounts by well-known sociologists, economists and demographers.

At the onset, editor Ravinder Kaur, a noted professor of Sociology and Social Anthropology at IIT-Delhi, highlights that the gender balance in Asia is significantly shaped by the “male biased sex ratios” of India and China. Kaur points out that rapid fertility declines in the two countries, resulting from China’s one-child policy and India’s two-child norm, coupled with son-preference and the advent of sex determination technologies, has contributed to an excess of males and a shortage of females in both countries.

Once the proposition is explained, the respective authors dealing with diverse subjects elaborate on the social consequences of gender imbalance in India and China. Of all possible outcomes and consequences, “The Marriage Squeeze”, mentioned by almost all contributors in the book, comes across as the most striking.

What is “the marriage squeeze” and why are India and China likely to face it in the coming years?

In layman’s terms, marriage squeeze is one of the fundamental consequences of the sex ratio imbalance which leads to mismatch in the “marriageable population”.

“A shortage of women implies a male marriage squeeze, while a shortage of males implies a squeeze against women,” explains Kaur.

As per the assertions of demographers, the possibility of marriage depends on the supply of potential mates, which in turn is influenced by the sex ratio at birth, the population age structure and marriage patterns. Therefore, when “fertility declines rapidly and is accompanied by female-biased sex selection”, a far lesser number of women are born and enter the “marriage market”.

“It is important to note that the effects of the marriage squeeze are likely to be felt more than twenty years after the appearance of skewed sex ratios,” the book points out.

But what is the likely impact of the marriage crisis on left-out men?

The book maintains that due to the economic, social, moral and psychological importance of marriage in both the Indian and Chinese societies, the “shortage of brides” has taken on immense importance in the public imagination, and as the demographers point out, it has become one of the most significant negative impacts of the sex ratio imbalance.

“With age, single men become a subject of ridicule amongst friends who have settled down,” says one of the respondents from a Haryana village, quoted in the book.

In the cultural context of China too, “singlehood is a state of frustration, and even of deprivation”, which in the likely scenario, is expected to have adverse effects on the left-out men. The book also claims that men living in rural areas are likely to “suffer more” as the bride shortage is often exacerbated by “women moving to urban or more prosperous areas”.

Monica Das Gupta’s chapter “China’s Marriage Market and Upcoming Challenges for Elderly Men” mentions that the proportion of never-married in China will be especially high among poor men in low income provinces, which are “least able” to provide “social protection programmes”. Other factors resulting in men remaining unmarried, according to the book, are addiction to drugs or alcohol, disability, and among other factors, social stigma. The marriage squeeze against men, the book notes, can be compounded by geographic factors such as residence in a less-favoured location.

Interestingly, the findings of the book suggest that under conditions of a male marriage squeeze, “women who are similarly disabled or whose reputations are similarly tarnished” are more likely to find spouses than men. At the same time, strictly in the Indian context, the consequences of the marriage squeeze are made worse by the fact that the traditional modes of dealing with bachelorhood are diminishing as the joint family declines and nuclear families become less welcoming of unmarried relatives.

The book finds that the marriage squeeze is also likely to have consequences on dowry and economic behaviour revolving around marriages.

“It is commonly expected that with the scarcity of women, the direction of marriage transactions would be reversed. It is conjectured that in India, dowry would decline, with some form of bride price taking place. In China, the effect is seen in the rise in bride price as men compete for scarce women,” writes Kaur.

So what should be the way forward?

The general view among scholars in the book is that “self correction” of skewed sex ratios cannot be left to happen by itself over a long duration.

“Rather, communities and governments need to take proactive steps to engender an equal value of the girl child. There is also a need to address the negative social consequences of sex ratio imbalance, which will continue to unfold in the future,” Kaur maintains.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Bhavana Akella,

By Bhavana Akella,

Title: Koi Good News?; Author: Zarreen Khan; Publisher: Harper Collins; Pages: 384; Price: Rs 250

The uncomfortable question “are you pregnant?” is faced by most women within months of being married — often a result of societal expectations which dictate a woman be a mother and embrace motherhood, irrespective of her choice.

Through the story of an Indian couple, Ramit Deol and Mona Mathur, who face endless questions on whether they’re expecting, the book attempts to explore the intrusiveness and pressure that couples, particularly the women, face to become parents.

Delhi-based Zarreen Khan, 37, a former marketing professional, draws on her personal experiences before she became a mother of two young boys, to create the characters of the book.

Remaining childless four years into marriage, Ramit and Mona’s attempts to battle questions of ‘Koi good news?’ (any good news) before Mona becomes pregnant and then receiving tonnes of advice on pregnancy from family, friends and several others once they’re expecting forms the story.

With a blurb that reads ‘Soon to be a major motion picture’ the bright fuschia-pink coloured book covered in glitter on its cover screams nothing but drama and Bollywood.

Filled with soap opera-like narration and conversations between characters scripted like monologues or personal blog rants, the book relies heavily on cliches and cringe-worthy anecdotes.

The humour in the book offers nothing more than instances like Mona’s sister finding Ramit’s ‘Humpty Dumpty’ briefs and chocolate condoms, and Ramit revelling in figuring out that having a maid named Lakshmi made her Lakshmibai (Bai in Hindi meaning maid) and hence the Rani of Jhansi.

Ramit’s wishes to live in an era of “servile wives instead of henpecked husbands” when asked to pack his own clothes, Mona feeling proud for having found a maid who is “clean, hasn’t stolen anything in three days”, and feeling anxious that there was “no filmy chakkar, no filmy fainting” (dizziness and fainting like in films) only depict the privileged and spoilt urban bourgeoisie.

While the book aims to address a legitimate issue — the excessive interest among Indian households in others’ sex lives — the unreasonable and intolerable characters make the story highly unrelatable.

(Bhavana Akella can be contacted at bhavana.a@ians.in)

—IANS