by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

Book: The RSS – A View to the Inside; Authors: Walter K. Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle; Publisher: Penguin; Pages: 405; Price: Rs 699

In a book released this week, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has been projected as “the most influential cultural organisation in India today”. The implications of the Sangh’s functioning on India’s culture, particularly in the context of Hinduism, or what is called Hindutva, is well known but is this projection an appeasement of the all-powerful Sangh by providing them legitimacy in what is billed as a scholarly offering “backed by deep research”, or is it worthy praise bestowed in the light of its work in the culture domain?

The offering at hand is the sum total of all aspects that the authors felt have led the Sangh to take its present shape — that of the ideological parent of the ruling government with country-wide presence and strong political affiliations. It reveals many answers but, for reasons best known to the authors and publisher, it deflects, ignores and often beats around the bush when it comes to tackling the most pertinent issues related to the Sangh in contemporary times.

Let us begin with two chapters in the book titled “Ghar Wapsi” (Homecoming) and “Protecting the Cow”. Both of these issues have gained prominence ever since the current RSS-backed government came to power in 2014 and has led to numerous instances of mob violence and lynching. The horrors arising from some (of many) recorded instances have shaken the nerves of right-thinking individuals and has caused fear among the minorities, but the generosity with which the authors tackle the subject is appalling.

The book elaborates on why protecting the cow and ghar wapsi hold such immense significance for the RSS, charting the beliefs of its idealogues Hedgewar and Golwalkar, and then draws a case study around the BJP’s dealings with the beef issue in the Northeast, where the ruling party sort of accepted it as it is a norm in the region.

It quotes a slew of prominent RSS and BJP leaders who contend, like the Sangh’s prachar pramukh Manmohan Vaidya, that “we (the RSS) don’t tell society what to eat”, adding that even people who eat beef could become its members.

Their assertion, however, is in stark contrast to the ground reality where members of the Sangh’s affiliates have been directly responsible for horrendous acts of violence in the name of the holy cow, dearer to the organisation than those lynched for slaughtering and, supposedly, consuming its meat.

The authors fail to raise tough questions despite their “unprecedented access” to key leaders of the Sangh, who are otherwise largely unapproachable by mainstream media.

And then there is “What Does Hindutva Mean?”, an elaborate chapter on the philosophy of the Sangh. Here again, the Sangh’s leaders paint a rosy picture of all things good in their philosophy. They say, as the book quotes them, that India is “a civilisational nation state” and that the RSS has never talked of making Hinduism a state religion.

The book points, flatteringly, to RSS literature, which, according to the authors, speaks approvingly of the religious and cultural diversities. Again, there is no meeting point between their words and ground realities, and what is more, the authors just let that be, without probing further.

The book goes on to quote RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat as saying that forcing others to chant “Bharat Mata ki Jai” is wrong and that “all people living in the country are our own and we can’t force our ideology and thinking on them”. Really, the authors should have asked some questions here as well, but they do not.

Moving on, there is a chapter on “Indianising Education”, where the authors claim that within months of the BJP’s victory in the 2014 general election, the then HRD Minister Smriti Irani “met with senior RSS figures” who wanted “the essentials of the Indian culture” to be reflected in school curriculum across the country.

It further mentions that in view of the “importance of the HRD Ministry in implementing the RSS goal of ‘indianising’ education”, the party selected Prakash Javadekar to replace the controversial Irani.

“Just a month after assuming his new post, Javadekar called a meeting that included senior RSS and BJP officials and other constituents of the Sangh parivar engaged in education,” the book says.

The motive of this meeting, says the book, was to discuss “the draft education policy earlier initiated by Irani” and to seek “suggestions to instill nationalism, pride and ancient Indian values in modern education”.

Notably, the over-400-page book’s actual text runs till page 256, after which is the appendix and notes section, which go on for about 150 pages. It also charts brief biographies of the RSS leadership, in glowing terms, and its constitution.

Even though this book is a missed opportunity as there is much more — and of utter significance both to the RSS and the country — that demanded exploration, it is not devoid of merit.

This book’s big achievement is in charting the journey of the Sangh — how the once banned organisation came into the mainstream, mobilised voters and played a crucial role in the 2014 general election, as it is expected to play in the coming election too.

But in its totality, the sense that a reader gets after reading this book is a glorification of the Sangh. It describes the inner working mechanisms of the organisation but fails to point out the outcomes resulting thereby.

The book surely has a lot of substance but can one possibly look at a raging fire and ignore those being burnt in it? This book does just that.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in )

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

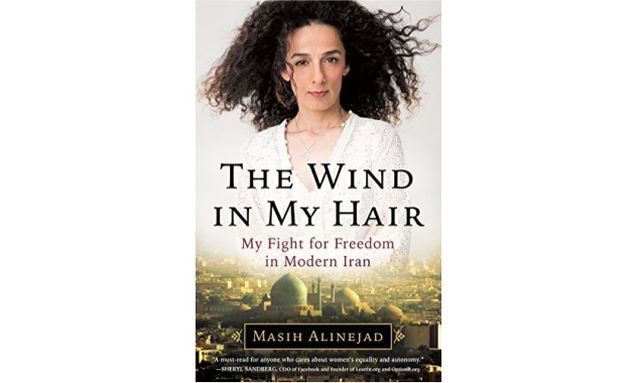

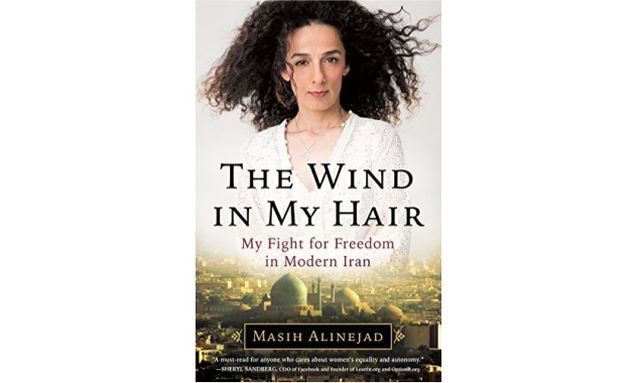

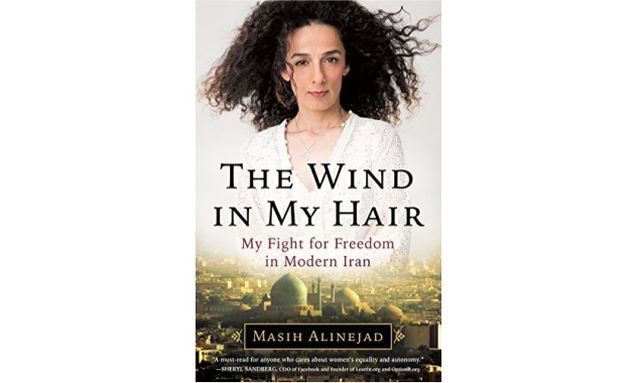

Book: The Wind In My Hair; Author: Masih Alinejad; Publisher: Little Brown UK/Hachette India; Price: Rs 699; Pages: 394

A courageous woman, driven by nothing but her insistence on living life the way she wanted to, untied her hair and let the beautiful curls flow over her shoulder. And all hell broke loose — she had defied the local law that stated women must wear a veil or hijab over their hair while in public.

Iranian journalist and activist Masih Alinejad’s incredible story of fighting for what she believed in and how she founded a major movement for women around the world with the simple removal of her hijab, is captured in her aptly titled memoir, “The Wind In My Hair”, out this month in India.

She recalls that as a young girl she travelled from her small village of Ghomikola to the city of Babol to attend high school. Here she saw that most young women did not wear the “chador”, a large cloak that leaves only a woman’s face visible, and thus decided to stop wearing one herself.

But her father became furious. “You make the devil blush with your sinning. You have brought shame on me, brought shame on your mother. You have ruined our reputation,” he said, scolding her. Ironically, when she was being scolded she was clad in a hijab.

Many years later, when Alinejad was a reporter covering the Iranian parliament and was accompanying a commission on a pilgrimage to Mecca, she along with two other female reporters decided not to wear the chador as it was very hot. But she was dressed in a hijab, a dress, trousers, and a long jacket.

“You are shameless — you have no morality. You have brought shame on the Iranian delegation,” a male reporter shouted at her.

Alinejad was very young when the 1979 Islamic Revolution swept across the country. What followed was a diktat that required all women in Iran, including visitors from other countries, to wear the hijab.

“I was taught that women’s bodies encouraged men to commit sin,” Alinejad writes. She also points out that female members of her family even slept wearing the hijab.

In her teens, she was sent behind bars and was subjected to what she calls “intense interrogation” as she had sided with a political group critical of the Iranian government. But the series of unfortunate events had just begun as, several years later, her husband would leave Alinejad for another woman. However, the courts granted him full custody of their three-year-old son.

All of these events, one after the other, sparked anger and outrage and gradually shaped Alinejad into somebody who defied rules and called for freedom. She went on to write scathing articles that exposed corruption and targeted the supporters of the then Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. She was forced to leave the country.

First in London and currently in New York, she lives in exile and has little hope of returning to her native Iran. But after her ouster from the country, she has been actively campaigning against the compulsory hijab law and policing of women’s bodies back home.

The turning point came in 2014 when she posted a photograph of herself in London — without a hijab — on Facebook. This was followed by another similar picture, but this one was taken while she was still in Iran. Both the pictures communicated strong messages as her hair was blowing freely in the wind.

She then called on the women from Iran to post similar pictures of themselves without the hijab in public places and this became a movement of sorts. Across Iran, women started posting pictures of their uncovered hair on Alinejad’s page in open defiance of the strict religious beliefs of their country (and often, their families) while also sharing their personal stories about this powerful mode of expression.

She titled her campaign as “My Stealthy Freedom” and states in the memoir that it celebrates “the moments of small rebellion, the tiny acts of defiance that allow us to breathe, the guilty pleasure of breaking unjust rules”. The page now has more than a million followers on Facebook.

She points out that she is not against the hijab but against compulsion, insisting that women in Iran should be allowed to choose what they wear and how they wear it.

In its totality, the memoir tells a compelling story with courage. But the almost-400-page book is often repetitive and could have become a more pleasurable read with some editing.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Sarwar Kashani,

By Sarwar Kashani,

Title: “The Unending Game: A Former R&AW Chief’s Insights into Espionage”, Author: Vikram Sood; Publisher: Penguin Random House; Pages: 304; Price: Rs 599

What do you expect from a book that promises insights into the world of espionage? Ian Fleming’s James Bond picking up beautiful women during his mission to serve national interests? Or maybe flame-haired female Russian spies using their sensuality to gain access to the American national security establishment?

No! That happens only in the world of fantasy.

The real world of espionage is drab but nonetheless thrilling. The real-life characters don’t drive flashy sports cars, unlock safes, wear jazzy clothes or are masters of martial arts. They are anything but 007s. They are the antitheses of Bond. They look unassertive in their demeanor. But behind the unnoticeable and poker-faced expression lives a cunning, ruthless agent. The real spy.

“James Bond is fantasy, George Smiley is reality,” says Vikram Sood — a career intelligence officer for 31 years who retired in 2003 after heading India’s external intelligence service, the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW) — in his debut work of non-fiction “The Unending Game: A Former R&AW Chief’s Insights into Espionage”, published by Penguin Random House.

George Smiley is a fictional character by novelist John le Carré. Smiley, a career intelligence officer with “The Circus”, the fictionalised British overseas intelligence agency, is a central character in le Carré novels — the latest one being “A Legacy of Spies”.

“In the strictest sense, a spy who completes a productive career without being discovered and settles down to quiet retirement is a successful spy,” defines Sood, who is now a not-so-quiet adviser at the Observer Research Foundation where he writes on India’s strategic affairs and national security.

Sood’s 300-plus page book about the tradecraft of intelligence largely explodes the prevalent perception about the “second oldest profession but just as honorable”. This includes a mystique or even a glamourised aura that the worlds of fiction and cinema have created around it.

The book is not a former spy’s personal memoir, nor is it merely about the R&AW. It is an attempt to throw light on the practice of espionage in war-ravaged 20th Century and the differently tumultuous 21st Century and tells us a bit about the security challenges India has faced or may face in the future — more so in the virtual world of cyber space.

The retired spymaster, of course, talks about the issues he faced as the head of R&AW but the main purpose of the book apparently is to deal with the theory of espionage — mysteriously shrouded or unduly glamourised.

Sood may have retired as an Indian spy but the anti-Pakistan flame he has kept alive all his career has not been snuffed out. It is evident in an elaborate account of Pakistan’s quest for the “Islamic” nuclear bomb. In fact, the prologue, which sets the pace and the narrative of the book, details how Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto famously said “we will eat grass or leaves, even go hungry but we will get one (nuclear bomb) of our own (because) we have no other choice” if India went ahead with its nuclear weapon programme.

Sood recalls a recorded event at Cafe du Trocardo in Paris in November 1978 when the Pakistanis were shopping for the nuclear bomb across Europe.

“‘Forget chasing the plutonium route. Uranium is the real McCoy,’ he said to the other man. The two had met for coffee that Sunday morning and then drifted away together towards Avenue Poincare to their cars. As one of them unlocked his car, the other slipped him an envelope.”

It was after R&AW’s years of a furious hunt all over Europe to lay hands on any evidence of Pakistan’s pursuit of nuclearisation as the agile Pakistanis kept moving from Germany to the Netherlands, then to Belgium, France, Switzerland and the UK.

Until then the R&AW officers had scoured the globe to find out how and from where the Pakistanis were acquiring material and technology.

“The envelope contained a document that clearly indicated that Pakistan had obtained 20 high-frequency inverters essential for enriching uranium. The first order had been placed through a West German firm — Team Industries.”

The intelligence was passed on to the civilian government in India to alert the world about Pakistan’s clandestine nuclear programme.

But Sood, little short of disparaging, says the R&AW, after navigating the labyrinth path to Pakistan’s bomb, “had no support or sympathy from the Prime Minister of the day, Morarji Desai, an acerbic Gandhian who did not want to have anything to do with intelligence collection about threats to the country, much less with matters relating to nuclear weapons acquisition”.

Desai “went about systematically decimating” the agency. Stations were shuttered, budgets slashed and “sensitive operations that had taken years to build” were also closed.

“Intelligence agencies,” Sood writes, “are the sword arm of the nation” and perhaps that is why “external intelligence, espionage and covert operations are a country’s first line of offence and defence”.

The book is a must-read for intelligence practitioners, security or strategic affairs experts or even academics — for those who are interested in knowing about the the real, not-so-raunchy or glamorous side of the world of espionage. It is full of action sans drama. But then facts are facts, and they need not be dramatic. To read this not-so-simmering account is to come in from the cold — the “Cold War”, I mean.

(Sarwar Kashani can be contacted at sarwar.k@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books, News, Politics

By Chinmaya Dehury,

By Chinmaya Dehury,

Title: Naveen Patnaik; Author: Ruben Banerjee; Publishers: Juggernaut; Pages: 226; Price: Rs 469

How did a man, spending his early days on Delhi’s cocktail circuit, defy stereotypes to script an enviable success story that has few parallels in the history of modern Indian politics? What led Naveen Patnaik, who had nothing to do with politics for the first fifty years of his life, become one of India’s most enigmatic politicians?

And, how did Patnaik, who remains the most inaccessible Chief Minister in the history of Odisha, rule the state for four consecutive terms and remained undisputed leader even without knowing the mother tongue of the masses? The answers to these and many other questions are unveiled by veteran journalist Ruben Banerjee in his biography of the Odisha Chief Minister.

Although he first become the Chief Minister by virtue of being his father’s son, Naveen Patnaik made a smooth and effortless transition from his bohemian days in Delhi’s cocktail circuit to a cunning and consummate politician and the longest serving Chief Minister of Odisha.

The author, who had access to Naveen Patnaik during his early days in politics, has unveiled a mine of information unknown to the world at large in the book.

Since Patnaik is considered a mysterious and unpredictable man for his omissions and commissions, the book, without a doubt, is a fascinating and interesting read for anyone interested in Odisha politics or in just the person who is Naveen Patnaik.

The book also dispels the popular belief that it is Patnaik, not someone else, who calls the shots in the government and the party as well. It, however, does mention about the over dependency of the chief minister on bureaucrats rather than on ministers to run the administration.

Patnaik, the book charts, entered into politics in 1997, founded the Biju Janata Dal (BJD) and become the party president, a post that he still holds. He became the Chief Minister of Odisha for the first time in 2000 with the help of alliance partner Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), riding on the sympathy following the demise of his legendary father and former Chief Minister Biju Patnaik and the public’s anger over complete mismanagement by Congress government of relief measures post the 1999 Super Cyclone that had devastated the state.

The author has also articulated how Patnaik, once a political novice, ruthlessly eliminated every possibility of an opposition within the party, real or imaginary, even before it took shape and banished his opponents into political wilderness to consolidate his position as the undisputed leader in the party and the state.

A case in point is the ouster of Bijoy Mohapatra, once a powerful minister in the Biju Patnaik cabinet and chairman of Political Affairs Committee (PAC) of BJD.

Mohapatra had chosen most of the candidates and they were all his men in 2000 elections.

But when he was chairing the PAC meeting in Bhubaneswar, Patnaik, being the president of the party, cancelled Mohapatra’s nomination as the candidate from Patkura and chose another as the party candidate just barely few hours before the completion of nomination process leaving no room to Mohapatra to enter the Assembly.

Patnaik, rather suave yet cunning, has also ensured that Mohapatra did not enter the assembly even till today. As the author rightly pointed out “Naveen the politician had shown the ability to outsmart the smartest of them”.

After he became Chief Minister in 2000, he continued to eliminate his possible challenges within the party starting from Dilip Ray, a businessman-politician, to Nalinikanta Mohanty, then BJD’s working president and second only to Naveen in the party hierarchy.

The book also highlights the protégée-mentor relationship between Naveen Patnaik and Pyari Mohapatra and how Mohapatra had staged an abortive coup on May 29, 2012, when Naveen was in UK.

Even though the author has elaborated on the abortive coup, a few answers remain elusive — including was it really a coup or just a media creation?

The author elaborately describes on how the TINA factor helped him to rule the state for so long and how he remained the darling of the masses, bucking the anti-incumbency factor.

“Members of one group, in particular, vouch vociferously for the chief minister’s integrity. These are an overwhelming majority of Odisha’s 200 lakh women, the chief minister’s trusted vote bank. Naveen is a bachelor, but his emotional bonding with the state’s womenfolk is remarkable,” the book says.

The book also highlights how Patnaik has mastered the art of shifting the blame on someone else to remain Mr. Clean despite the fact that some of the biggest scams –mining, chit funds — in the history of the state took place during his watch.

“The key to Naveen’s success is that even though he has indulged in political machinations and subterfuge, he has largely come out of them without blemish, skillfully sidestepping scrutiny and deflecting criticism. He is still viewed by many as innocent and incapable of the vileness of an ordinary politician. And when something goes horribly wrong somewhere in the state, there is always someone else who shoulders the blame, sparing Naveen any taint. That he is single, soft-spoken and always deferential has helped in nurturing Naveen’s image,” the book says.

By rough estimates, Patnaik has so far shown the door to some 46 of his ministers on one pretext or the other, it said.

The book also mentions the possible challenge for Patnaik in the 2019 polls with the rise of BJP and union minister Dharmendra Pradhan. As the author points out, “The battle for 2019 promises to be a test of guile, image and stamina.”

The book is a required read for those who want a balanced telling of the Chief Minister’s journey so far. Also, for those interested in the political journey of Odisha, including the rule of Biju Patnaik and J.B. Patnaik, the book is a great repository.

(Chinmaya Dehury can be contacted at chinmaya.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: The Surajpur Connection; Author: Prabhu Dayal; Publisher: Zorba Books; Pages: 160; Price: Rs 199

The hardest journey to undertake, if it is even possible, is to return to one’s childhood home, particularly if it was a happy period. But even this happiness — which may not be everyone’s lot — can be disrupted by forces beyond relentless time. Within a twinkling of eye, all comforts and happiness being replaced by pain, deprivation and oppression.

And even if you can surmount the problems and even manage to return, it will never be the same.

It is this inexorable truth of life that former diplomat Prabhu Dayal portrays in his second work, a novella which is poignant and heart-wrenching but also showcases hope, and how kindness and generosity — no matter how expressed — can be encountered as often as cruelty and self-interest.

Beginning with an evocative prologue, where a well-heeled expatriate businessman, on a trip to Mumbai, is casually reading the paper in his hotel room when something catches his attention and forces him to change his whole schedule and leave for north India.

The scene then shifts over a quarter century or so into the past, to the rural areas in Uttar Pradesh’s Allahabad, where a prominent and influential landlord has repeatedly spurned the (then) all-powerful Congress’ repeated requests to be the party candidate for the coming elections (1967).

The reason is simple — for “after years of pills, prayers and pilgrimages”, he and his wife finally have a son, they fondly call Sonu.

But while his parents are overjoyed, there are others, who pretend to adore him as much but have darker intentions in their heart, and soon act on them without mercy.

One post-monsoon afternoon, the household is sleeping and a four-year Sonu playing outside when he goes missing. An extensive search is made, police swing into action, desperate efforts are made to find him, but there is no trace and not even a ransom demand.

Little his grieving parents know that their innocent son has become the victim of a particular dreadful crime and is even no longer in the country, but far away beyond the seas, doing a dangerous chore in a desert land.

But while after six months of torture, danger and worse, Sonu and a fellow prisoner do manage to escape, will the unforgiving desert allow them to survive? Will he, if he stays alive and manages to find his way home to his own land, by some miracle, be able to make his way home, given he doesn’t know the name of his parents or where he lived, despite this promise made to himself?

And what is the connection between Sonu and the successful businessman we meet in the initial pages?

These are all the questions the author engagingly answers,in this short but powerful account which covers a fairly wide spectrum of the human condition — from depravity to decency.

In his second book after the uproarious yet incisive “Karachi Halwa” about his stint in Pakistan, Ambassador Dayal moves effortlessly and adroitly to fiction.

With his four-decade-long service having encompassed the Middle East, Europe and America, he makes good use of both his roots and experience, especially in the Arab world, to sketch vivid portraits of mofussil Uttar Pradesh to Dubai, in its transition from a small town to a glittering megapolis, as well as a range of characters, spanning evil uncles, oppressive trainers, kind-hearted sailors, maternal teachers and so on.

Though at a superficial level — in its plot, set pieces, telescoped action, and its rather dramatic denouement and so on — it may seem like a Bollywood film, it is not so simple, for it raises some vital questions and issues.

These include, but are not limited to, identity, the concept of home and family, the need to be anchored, the (transient nature of) happiness, whether loyalty deserves the name if for an evil purpose, can kindness be graded on its intention, and much more, which makes this story a short but most engrossing and thoughtful read.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS