by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

Book: Heart – A history; Author: Sandeep Jauhar; Publisher: Viking Books; Pages: 269; Price: Rs. 599

Dedicated to the beating heart, Dr. Sandeep Jauhar’s latest book ‘Heart – A history’ provides a thumping tribute to the protagonists — some legendary some unsung — of medicine, who over the years have innovated and persevered to find cures for cardiac ailments through landmark breakthroughs in their field.

Do not mistake ‘Heart – A history’ as a health digest. Neither is it a prescriptive scribble on how to keep yourself healthy.

‘Heart’ also spans through progress made vis-a-vis heart care through civilisations right till date, while also combining personal anecdotes and heart disease-related stories from Jauhar’s own family and his peers.

Jauhar’s writing style reads like a Arthur Hailey manuscript, engaging the reader with ease and keeping you hooked with interesting personal anecdotes, historical nuggets, factual nuggets, humorously-narrated tales of torturous perseverance and recounting how some of the most important inventions related to treatment of cardiovascular diseases, were, in fact, stumbled upon by accident.

For example, the story of the invention of a pacemaker — a device which generates electrical impulses via electrodes to contract the heart muscles and at the same time regulate the heart’s electrical conduction system — which it seems was conceived (in a way) in a barn and eventually born, thanks to a transistor and a mistake by electrical engineer Wilson Greatbatch.

In the 1950s, Greatbatch, who was testing instruments to monitor heart rate and brain waves in sheep and goats at a livestock farm near New York, when he learned about heart block from two surgeons, who were around on a summer sabbatical.

Years later, when he was tinkering with the newly-invented radio transistors, he accidentally inserted a resistor in the gadget’s circuit, which in turn triggered rhythmic pulse. Viola! The pacemaker was born.

“I stared at the thing in disbelief and then realised that this was exactly what was needed to drive a heart…. For the next five years, most of the world’s pacemakers used (this circuit) just because I grabbed the wrong resistor,” Jauhar quotes Greatbatch as saying.

The “taking charge of the human heartbeat” was a seminal moment in the history of science, according to Jauhar, because “from antiquity to modern times, philosophers and physicians had dreamed of taking charge of the human heartbeat.

Like a good doctor humours his patients, Jauhar also leaves a trail of humour you cannot miss in his writing, which is what makes reading him easy, even for the layman.

For example, when he writes about how the US Surgeon General’s caution on cigarette packets eventually came to be in the 1960s, he slips in a humorous lozenge in parenthesis, like your friendly family doctor.

“By the early 1960s, a definite association had been also been made between cigarette smoking and heart disease (smokers in previous studies hadn’t lived long enough go draw definitive conclusions). This led to the first Surgeon General’s report detailing the health hazards of smoking. In 1966, the United States became the first country to require warning labels on cigarette packets,” calling the President Richard Nixon era legislation as one of the great public health triumphs of the second half of the 20th century.

Through the book, the writer also introduces medical professionals like Daniel Hale Williams, an African American doctor who performed the world’s first open-heart surgery in Chicago; and C. Walton Lillehei, who connected a patient’s circulatory systems to a healthy donor’s paving the way for the heart-lung machine — legends who redefined heart treatment, to the reader.

However, apart from chronicling the evolution of the disease and medical innovations which tried to arrest and cure heart ailments, Jauhar also tries to pitch the reader a more holistic perspective, to make the point that medical technology is limited and that control of heart disease largely depends more on the life choices we make.

The book is extremely relevant to India, where deaths due to heart disease have risen by as much as 34 per cent over the last 26 years.

(Mayabhushan Nagvenkar can be contacted at mayabhushan.n@ians.in)

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

Book: The Beauty of All My Days; Author: Ruskin Bond; Publisher: Penguin; Pages: 183; Price: Rs 499

Life is one epic story and the experiences that each individual has is varied and distinct. Author Ruskin Bond has been penning his life experiences — in both fiction and nonfiction — for well over six decades now and is back with a fresh memoir.

Jacketed in a surreal cover, with colourful flowers calming the reader’s impatient eyes, “The Beauty of All My Days” is dedicated to “all the kind readers and well-wishers who wait patiently outside Mussoorie’s Cambridge Book Depot on Saturday afternoons”. As is customary, India’s grand old author visits the book shop to interact with his readers. “It is a special time for me when I meet and sign their books,” he notes in the dedication section of the just-released book.

The book has 10 chapters and numerous photographs of the writer’s private life, or as Bond describes it, writerly life. But Rusty, as his fans lovingly call him, has penned several similar volumes in the past such as “Lone Fox Dancing” and “Looking For the Rainbow”. Every time you think you know enough about the writer, adored so dearly across the country, there is something new that he throws at you.

And he does it again in “The Beauty of All My Days”.

In the memoir, Bond wonders if his life would have been very different had his parents “not committed the mistakes and indiscretions that shaped their lives and mine and lives of my brother and sister”. Here, those who have read his previous works would recall the not-so-successful marriage of Bond’s parents — Aubrey Bond and Edith Clarke.

So is Bond being repetitive? Perhaps yes, but he adds layers of reflections and shows to the reader that there are different interpretations of human memory, and the human mind sees them differently at different stages of their lives. “Memory improves with age,” he had asserted in a previous book, and the offering at hand shows that the improvement in memory is perhaps a more mature view of the past.

“…had they (his parents) not met, I would not have come into this world, and that would have been a pity because, on the whole, I have had a happy and fulfilling life and have given enjoyment to a few readers, young and old. I’m a person without many regrets…

“I inherited nothing of a material value — not a penny, not a room that I could call my own,” recalls the author who began his literary venture with “A Room on the Roof”, whose protagonist “Rusty” became the life-long synonym for the writer.

“… but I did inherit my father’s intellect and my mother’s sensuality, and possibly the two combined to turn me into a writer,” Bond quips.

Contained in the memoir are tales of finding his own space, of his writing room, picnics and the little things that often go ignored in our fast-paced lives. But perhaps the most significant revelation the book carries is why Bond never writes about politics.

Bond notes that since “everybody else does” he thought he should be the exception and “concentrate instead on birth and death and the interval between”.

“The trouble with political issues is that they come and go very quickly, and if you make them a part of your story it is apt to date the writing. A short story I wrote 60 years ago, about meeting a blind girl on a train (The Eyes Have It / The Eyes Are Not Here / The Girl on the Train), is still read with pleasure by young people today; but if the story had been about meeting a politician who was about to open an eye camp in his constituency, would it have the same impact today?

“The topical is for the day’s news media. The loves of… Romeo and Juliet, or Laila and Majnu, are timeless storytelling,” he writes.

But he also asserts that he hasn’t ignored politics or political issues. “Different governments, different parties in power, different eras. I am fortunate to have witnessed a little history; political history,” he notes, before writing at length on India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

He ends the memoir by answering a question he is often asked: “Haven’t you ever thought of living in another country — of settling down somewhere else?”

This is where the tragedies of our time creep into his pages.

“As a boy I had romantic visions of Burma and the road to Mandalay. But it’s a harsh, intolerant land today. And I don’t see myself penning poems in a poppy field in Afghanistan, my intentions would be misunderstood. Further West, into Arabia and the Middle East, there is only death and disaster: Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya… When does the suffering end?

“America? I’m no Hemingway, I’m afraid of guns. And he shot himself, didn’t he? South America, up the Amazon? But they’ve cut all the forests away,” laments the 84-year-old writer.

Bond reflects that “Destiny, or the Great Librarian” brought him to Landour’s humble Ivy Cottage where he has lived since 1981.

“Mother Hill near Mother Ganga, and here I have spent my best days and done my best work. And here I stay, until I have written the last word.”

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By M.R. Narayan Swamy,

By M.R. Narayan Swamy,

Title: The Life and Times of Yogananda; Author: Philip Goldberg, Publisher: Hay House India; Pages: 336; Price: Rs 399.

It will be an understatement to say this is a gripping book, sympathetic yet critical. With his passion for meticulous research, Philip Goldberg has authored what is undoubtedly one of the most stirring and brilliant accounts of a spiritual master, Paramhansa Yogananda, delving in particular into his life in the US that have largely remained shrouded in mystery. The result is this profound biography.

Goldberg makes it clear that he is not a disciple of Yogananda, which makes the book all the more enriching. Yogananda (born Mukund Lal Ghosh in Gorakhpur) achieved global fame with his 1946 masterpiece “Autobiography of a Yogi”. That seminal book is the reason why he still casts a spell, although he passed away decades ago. A professional writer for more than 40 years, Goldberg decided to essay Yogananda’s life because although the yoga guru spent almost all his adult years in America, less than 10 per cent of the “Autobiography…” is about that immensely productive and historically significant period.

Goldberg’s wide-ranging research led him to conclude that Yogananda, his quirks and idiosyncrasies notwithstanding, was an extraordinary human being, a spiritual prodigy, psychically gifted with exceptional inner powers and without doubt a self-realised yogic master. From a young age, he stalked God the way “Sherlock Holmes stalked criminals”.

But for one who moved to the US in 1920 unsure of his English, life wasn’t easy.

With his ochre robes and long hair, his mere appearance could invite ridicule, torment and even abuse. He endured sneers, glares, name-calling and even stone-throwing, but maintained his dignity. Worse, there were times when Yogananda and his close group didn’t have enough to buy food, so they would simply fast for a few days, says Goldberg, uncovering details never known before. Building the network he eventually did in the US was no joke because it was a time of coin-operated phone booths, long-distance operators, telegrams and letter writing. But Yogananda did it.

Only a handful of people came to his earlier “satsangs”. The numbers grew slowly, through word of mouth, as Yogananda began wandering across the length and breadth of America — much like Adi Shankara did in India centuries earlier. He went everywhere he could: Miami, Seattle, Oregon, Los Angeles, New York, Cleveland, Colorado, Boston, Utah.

Yogananda’s very name played a role in popularising yoga, then an unknown subject in the West. As he toured America, every time his name was mentioned or appeared in print, “yoga” became further legitimised in public mind. For someone who was reticent about public speaking at first, he became quite a performer. No wonder, his gatherings — where he spoke about God, yoga, meditation, the oneness of humankind — began to attract as many as 5,000 to 6,000 people. There were occasions when visitors had to be turned away because the venues were overflowing. A time came when The Los Angeles Times would call him “the 20th century’s first superstar guru”.

How did Yogananda succeed? Although his ingredients always contained elements from Hinduism, including karma, dharma, reincarnation, mantras, chakras and core principles of Vedanta, the combination of scientific rationality and respect for the Judeo-Christian tradition would become hallmarks of Yogananda’s teaching. Yogananda, says Goldberg, took the veneration of Christ a step further, producing a massive volume of written and spoken commentary on Jesus and his teachings. This triggered problems too. He was accused of selling out to attract Christian followers and also of “Chritistianising” Hinduism. His introduction of kirtan to America has been largely under-appreciated, the author says.

Once Yogananda attained VIP status, he was welcomed to the White House by President Calvin Coolidge (1923-29). Indeed, he had genuine love for America. He said the US was the most spiritual country, next only to his own India. He also met Mexican President Emilio Candido Portes Gil. What is noteworthy is that Yogananda makes no mention of these personal achievements in his “Autobiography…”, which is more about saints he met in his quest for God and less about himself.

But a time came when Yogananda had to face the worst of America: Media sensationalism, religious bigotry, ethnic stereotyping, sexual allegations and brazen racism. Life became difficult during the World War years as it affected revenue from class fees, books and magazine sales. Donations plunged. Worse, people he though were his soul mates suddenly ditched him and took him to court, causing him immense pain. On one occasion, he begged the Divine Mother: “Free me. Let me go back to India to serve you there.” It was not to happen.

Yogananda kept saying that he was using business in religion and not making a business of religion — as evidenced by the fact that no one was profiting financially from his work. When he returned to the US after a brief visit to India in the 1930s, he was detained for four days by US authorities for some obscure technical reason. But nothing derailed the “serious man with a serious and singular mission, a determined, disciplined, demanding dynamo who slept only three or four hours a night”. But Yogananda was fun-loving too. He loved popular comic strips like “Blondie” and “Bringing Up Father”. He loved to fly kites. And as a cook, he was a perfectionist.

Goldberg is clear that allegations of sexual derailment hurled at him have no basis. “Had I found verifiable evidence that Yogananda had sexual affairs or exploited female disciples, I would not have hesitated to report it. But I did not… My research did not uncover any credible evidence that Yogananda ever broke his vow of celibacy… No woman ever claimed to have had sexual relations with Yogananda — not even in posthumous letters, diaries or memoirs.”

In 1946, Yogananda took advantage of a change in immigration laws and applied for citizenship. His application was approved in 1949 and he became a naturalised US citizen. It was the year he took a train to San Francisco to meet Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister. And when he died, Yogananda was speaking about India.

According to Goldberg, Yogananda’s crowning achievement, and the most enduring monument to his earthly expedition, was the “Autobiography of a Yogi”. It has sold millions of copies and continues to be a best-seller. But in 1946, publisher after publisher rejected it — until the Philosophical Library went for it. That book, along with Yogananda’s other writings, has had a religious and spiritual impact that “is unique and unassailable”. As Goldberg says, no single person contributed more to East-West current than Yogananda.

(M.R. Narayan Swamy can be reached on narayan.swamy@ians.in)

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By R. Sedhuraman,

By R. Sedhuraman,

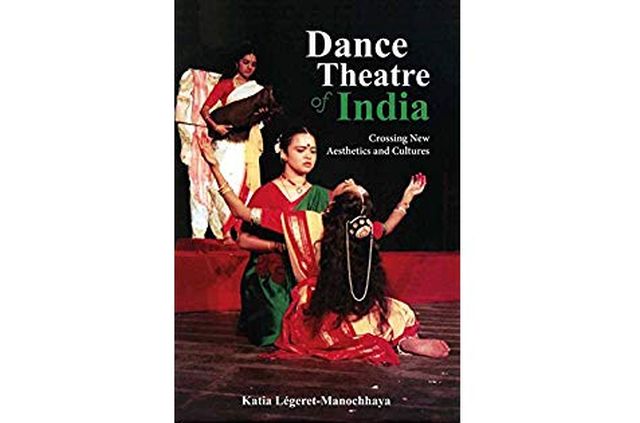

Book: Dance Theatre of India: Crossing New Aesthetics and Cultures; Author: Katia Legeret-Manochhaya; Publisher: Niyogi Books; Pages: 142; Price: Rs 650

In the 1930s, when the freedom struggle was gathering momentum, the British Raj slapped a ban on India’s actor-dancers, taking away their freedom of speech. They were not allowed to sing or dance on the stage.

To overcome this problem, renowned artists and institutions redefined classical dance forms such as Kathakali, Kuchipudi, Bharatanatyam and Odissi.

A number of actor-dancers and classical art schools introduced musicians on the dance stage to do the role of playback singers. The singer’s voice then became the voice of the actor-dancer.

This and many more interesting twists and turns in the evolution and development of traditional and contemporary Indian dance forms have been narrated in great detail in a new book titled “Dance Theatre of India: Crossing New Aesthetics and Cultures.”

The book has been authored by Katia Legeret-Manochhaya, Professor of Performing Arts and Aesthetics in the Department of Theatre at University Paris 8, and director of the research laboratory EA 1573, part of the doctoral school of EDESTA: Aesthetics, Sciences and Technologies of the Arts. Trained in Bharatanatyam (dance/theatre of South India) in 1979, she has created an international career for herself in this dance form. As a choreographer and director, Manochhaya has composed and staged several performances since 1998, mostly in Paris.

In the book, the author explores the various rasas of Bharatanatyam and other dance forms, both as a dancer and a researcher. The book transports the reader to a world of dance and drama where one can enjoy the various expressions of the artists in colourful costumes while narrating stories from all over the world.

She says she finds it difficult to classify Indian theatre and dance according to Western professional artistic categories. This is because actors in India are also dancers, musicians and storytellers. Bharatanatyam is a form of dance theatre like Kathakali or Odissi. In any case, reducing it to dance alone would be disrespectful to the immense acting work required to act out the stories of major literary texts such as the Mahabharata or the Ramayana, she points out.

The book carries a number of photographic portraits of various live dance performances to explain the author’s perspective to the readers.

The author raises several questions in the book, discusses the relevant issues and comes up with her explanations.

At the outset, she clarifies that she is interested in the new relations between dance and theatre. According to the most ancient principles from the Natya-sastra, a founding text in India for the dramatic arts, dance and theatre go hand in hand.

But are their coexistence and mutual inspiration still relevant now in India and internationally? How do today’s dancers use their rhythmic movements to deconstruct or transform cultural codes and inherent gestures from actors’ traditional vocabulary? Also, conversely, how does the intra-cultural approach of a rural experimental theatre that was specifically adopted in Rustom Bharucha’s research enable European influences or the idea of a universal comprehension of cultural codes to be resisted?

Similarly, why does dance seek to get away from the theatre as a place of production of a pre-established religious, social, political or economic meaning?

To better understand these processes, she says we could look at the gestural practices of actor-dancers who have been trained in “classical” styles. For example in the Kathak form, we look at how Akram Khan and the Master, Birju Maharaj, transform certain of their gestures to enhance communication with an audience from other countries. Conversely, street theatre in Bengaluru which are linked to NGOs appropriate and reuse culturally codified gestural languages to portray current affairs issues and social problems.

In classical arts such as Bharatanatyam, such borders are porous because creators have to simultaneously be choreographers, musical conductors and directors. An artist working in this field has three professions from the standpoint of Western categorisation of the arts. To help us understand how this idea of total art works, the aesthetic theories from the Natya-sastra, from its commentator Abhinavagupta along with those from the Abhinayadarpana and the Sangitaratnakara are precious but are also always linked to very precise staging techniques, the author says.

For example, the notions of rasa, creativity and improvisation will be analysed based on stagings of the Ramayana in the Mysore Bharatanatyam style.

Pointing out that Bharatanatyam is founded on exclusively oral transmission, she raises a doubt that it has been preserved as part of India’s cultural heritage.

“This art is founded on exclusively oral transmission. So how is it possible for it to be preserved as part of our cultural heritage,” she asks.

(R. Sedhuraman can be contacted at sedhuraman.r@ians.in)

—IANS

by Editor | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

Book: 21 Lessons for the 21st Century; Author: Yuval Noah Harari; Publisher: Penguin; Price: Rs 799; Pages: 352

Yuval Noah Harari, the million-copy bestselling author of “Sapiens” and “Homo Deus”, has returned with “21 Lessons for the 21st Century”, and the sum total of the arguments that he presents in the new book is that we are living in times when “unpredictability” has become the new norm.

Covering a wide range of issues critical in shaping how the human civilisation survives the 21st century, Harari sets out to answer some basic questions in the book. In fact, as he himself notes, most parts of the book have been composed in response to questions that readers, journalists and colleagues put to the author.

In answering these fundamental questions — like “How can we protect ourselves from nuclear war, ecological cataclysms and technological disruptions”, or “What can we do about the epidemic of fake news or the threat of terrorism” — Harari weaves a common theme of the need to maintain “our collective and individual focus in the face of constant and disorienting change”.

“If you try to hold on to some stable identity, job or world view,” Harari warns his readers, “you risk being left behind as the world flies by you with a whooooosh.”

The just above 300-page book touches on, and discusses in a thought-provoking manner, issues such as religion, nationalism, environment, Artificial Intelligence, social media, data privacy and liberty, among others, that have been subjected to constant changes in the light of recent upheavals. Harari holds that religion can have adverse impact on its followers, but like nationalism, which is threat to globalisation, it too has its uses.

“Does a return to nationalism offer real solutions to the unprecedented problems of our global world, or is it an escapist indulgence that may doom humankind and the entire biosphere to disaster?” he asks, before debunking the challenges of nuclear war, ecological damage, and the technological problems that may surface, or are already surfacing, as a result of rising nationalism.

“Each of these problems — nuclear war, ecological collapse and technological disruption — is enough to threaten the future of human civilisation,” he contends. “But taken together, they add up to an unprecedented existential crisis, especially because they are likely to reinforce and compound each other.”

But the sheer joy of reading Harari lies in the fact that he can impress his readers at the most unexpected junctures with some mind-expanding paragraph sandwiched between his observations and suggestions. And how does he do it?

The author uses literary devices and recent examples to arouse the reader’s curiosity. For example, he notes in the book that the Islamic State murdered thousands of people, toppled archaeological sites and demolished every sign of Western cultural influence after conquering parts of Syria and Iraq. Harari then adds that the same fighters robbed stashes of American dollars which had the faces of American presidents. They did not burn those currencies even though the notes glorified American political and religious ideals.

Harari suggests that religious fundamentalists and bigots too have an agenda at play. Whether it is the Islamic State, North Korean tyrants or Mexican drug lords, all bow before the all-powerful dollar.

Although,= Harari does not seem to be very impressed with the way human civilisation is marching ahead, there is no end of hope for him. As the book itself is titled “21 Lessons for 21st Century” it address the challenges by putting forth some lessons that the author has learnt, and believes can be useful for each of us.

Indian readers will also be pleased to note that the book has ample direct references to India. At one point, Harari notes that while thousands of years ago devout Hindus sacrificed precious horses, today they invest in producing costly flags. He refers to the hoisting of one of the largest flags in the world at Atari on the Indo-Pak border in 2017 and notes that “strong winds kept tearing the flag, and national pride required that it be stitched together again and again, at great cost to Indian taxpayers”.

“Why does the Indian government invest scarce resources in weaving enormous flags, instead of building sewage systems in Delhi’s slums?” he asks. “Because the flag makes India real in a way that sewage systems do not.”

Harari acknowledges that all the solutions he offers in the book may not work for everybody. “I am very aware that the quirks of my genes, neurons, personal history and dharma are not shared by everyone,” he notes, before elaborating on “hues” that “colour the glasses through which I see the world”.

All in all, “21 Lessons for the 21st Century” may be an eye-opening book for many. Even if one disagrees with Harari’s assertions or solutions, the merit of the book lies in opening up the issues in their totality, thereby allowing the reader to pause and contemplate on where we, humanity as a whole, are headed and if we can improve the prospects of our future by altering our actions in the present.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in )

—IANS