by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: Amazons – The Real Warrior Women of the Ancient World; Author: John Man; Publisher: Bantam Press/Penguin Random House; Pages: 320; Price: Rs 699

Myths can have great staying power, even beyond their original catchment area. This one began as a major concern (or even worry) of Ancient Greece’s patriarchal society and then spread across five continents over the coming centuries, inspiring, among others, the names of a great river and a global delivery firm, as well as a superheroine seen recently on film.

And the Amazons are reflected in some of the most effective fighters seen in the last two centuries, from the shock troops of an African king, a group of daredevil Soviet pilots during the Second World War and some doughty fighters of Kurdish paramilitaries.

But did this group of formidably fierce, horse-riding women warriors — who mutilated themselves to be better fighters, hated and avoided men (except for procreation from which they only kept the girl child and practised male infanticide), as per the Ancient Greeks — have a basis in fact or history, or were hearsay, rumour and (patriarchal) fears rolled together? And what is their significance?

In his latest book, acclaimed British historian John Man takes the plunge to find out, traversing cultural history, travel, archaeology, anthropology and gender relations among others.

Man, whose well-known books on Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan and Marco Polo, among others, combine history and personal travel experiences, says, as a child, he used to read comics about superheroes (which “includes superheroines and supervillains”) and while he grew out of them, he was recently impressed by one of their earliest characters.

“Only one appeals to me: Not because she’s been around for seventy years, not because she has recently starred in her own blockbuster, but because of the depth of her back-story. This is Wonder Woman, daughter of Zeus, princess of the Amazons,” he says, terming her “even more Amazonian than the Amazons of Greek legend”.

This, he says, is because she outstrips the original Amazons in the purpose for which the Ancient Greeks spun stories about them — which was not to extol their bravery or way of life. And there is “now much more to the Amazons than myth”.

And Man, starting from where Aristotle went wrong in his political categorisation of man, takes us to back in time to the boundless grasslands, stretching from Hungary to China’s Manchuria, where Wonder Woman had “real ancestral sisters”, who belonged to a “different way of life and a far more sophisticated one than the Greeks dreamed of”.

Exploring the Amazon myth in Greek culture, especially in Homer’s “Iliad”, as well as a conjecture of how the Greeks could have conceptualised it, he takes a brief but necessary digression to deal with the prevailing error of Amazons’ supposed custom of “burning off” their right breasts so as to wield their bows better, before moving eastward (in person too) into Eurasia to acquaint us with the Scythians — a generalised term for several related cultures of the steppes where both men and women were herders and warriors, as we learn from their excavated tombs.

Man then traces how the myth endured down the ages, influencing art, literature and popular culture, while “giving the names of Amazon not only to individual warrior women (and countless women fighting for countless causes), but also, more accurately, to very rare groups of women fighters” as the myth inspired and was also impacted by the real world.

This is achieved through the stories of present-day men — and women — who have succeeded in replicating the steppe warriors’ prowess in archery on horseback, in the attempts of Spanish conquistadors and others to find Amazons in the Americas and how these led to naming of a mighty river in South America.

He then brings out the cultural manifestations of Amazons in Europe from paintings to plays, in the comic book industry in the US and, more grimly, in wars from the European scramble for Africa, World War II and finally the conflict in Syria and Iraq.

Above all, it is a seminal look on the grounds (equality of sexes) where “barbarianism” trumps “civilsation” and how some institutions (patriarchies) can only survive by conjuring a threat.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: Hands: What We Do with Them – and Why; Author: Darian Leader; Publisher: Penguin Random House UK; Pages: 128; Price: Rs 499

If you think the current trend of people, publicly and privately, paying ferocious attention to their smartphones or other hand-held devices and furiously typing, clicking or scrolling away is technology making a travesty of human nature, you may well be wrong. For these habits may represent its crucial part’s latest preoccupation.

While the “radical effect” of the internet, the smartphone and the PC is said to be “on who we are and how we relate to each other” and whatever we make of the changes, psychoanalyst Darian Leader notes that experts stress that these are changes which have made the world a “different place” and the digital era is “incontestably new”.

“But what if we were to see this chapter in human history through a slightly different lens? What if, rather than focusing on the new promises or discontents of contemporary civilisation, we see today’s changes as first and foremost changes in what human beings do with their hands?” he poses.

For while the digital age “may have transformed many aspects of our experience, but its most obvious yet neglected feature is that it allows people to keep their hands busy in a variety of unprecedented ways”.

Leader, in this slim but more than a handful of a book, contends that the body part that most defines us humans is not our advanced brain but rather our restless upper pair of limbs. Thus, a considerable amount of our history and habits can be related to what we can do — or cannot do — with our hands and why we must keep them busy.

This, he says, brings us to examine the reasons for this “strange necessity” — to know why idle hands are deemed dangerous, how their roles for infants changes as they grow, what links hands to the mouth, and what happens when we are restrained.

“The anxious, irritable and even desperate states we might then experience show that keeping the hands busy is not a matter of whimsy or leisure, but touches on something at the heart” of what our existence embodies.

And to ascertain this something, Leader goes on to draw from popular culture (especially films, mostly horror and science fiction but also classics like “Dr Zhivago”), language, religion, social and art history, psychoanalysis, modern technology, clinical research, the pathology of violence and more to find the what, why, and how.

In this process, we come to know why zombies and monsters (like Frankenstein) are shown walking with outstretched arms, why newborns grip an adult finger so tightly that they can dangle unsupported from it, the reason for prayers beads in various religions (Leader misses out Hinduism), why nicotine patches may not help smokers, the constant preoccupation (for some of us) with texting, tapping and scrolling and our behaviour on public transport.

And as Leader is a founding member of the Centre for Freudian Research and Analysis, people will expect sex to figure somewhere and they will not be wrong — or fully right. For he only tackles one aspect, which involves the hand.

He recalls when friends and others asked him what he was working on during the preparation of this book, “my reply that it was to be an essay about hands produced the almost invariable response, ‘Oh! A book about masturbation!'”. He dryly notes that “the association appeared to be so intractable that it seemed foolish not to at least devote a chapter to this”.

His observations on hands and their motivations and manifestations break new ground and it will suffice to say that you will never look at fairy tales, from those of the Grimm Brothers to Arabian Nights to J.R.R. Tolkien, the same way again.

His chapter on violence seems a bit out of place, but Leader brings his argument a full circle as he closes on the compulsive use of technological devices what we (and their makers) must know about them.

More of a long essay than a book, it brings to fore to the issue that, despite all our technical prowess, we are still to plumb the mysteries of our mind and body, which can be more complex than anything we invent.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: What Would Nietzsche Do?; Author: Marcus Weeks; Publisher: Cassell Illustrated/Hachette UK; Pages: 193; Price: Rs 499

Your smartphone gets lost and you are worried about identity theft. Did you know that the basic issue underlying this predicament has already been dealt with by great thinkers centuries ago? That problems or issues of your love life have a philosophical basis? Or that someone most likely to sympathise with your wish to chuck up your conventional but boring job to follow what your heart desires is none other than Karl Marx?

The issue of the lost phone with all your vital details and facets of your life stems from the basic philosophical question: “What makes me who I am?”, and whether our changing body, thoughts and ideas, personality — and now possessions — affect this. And pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus of the “Ship of Theseus” conundrum, to Rene “I think, therefore I am” Descartes, have weighed in on this long before smartphones came into existence.

Then take the mysterious and maddening sphere of love.

In cases of broken hearts and what to do about them, we must know if there is a point to or benefit of suffering; the dilemma of whether you should tell a friend that he/she is being cheated by their partner rests on whether we have a moral duty to always tell the truth; and differing objectives from a relationship rise from views on sensual pleasures, subjectivity of experience and letting social conventions dictate our moral choices.

“Life has a habit of presenting us with dilemmas, some serious and some trivial, that require a bit of thought, and perhaps some guidance. And when it comes to thinking about problems, there’s nobody more skilled than the great philosophers,” says Marcus Weeks, who has been music teacher, taught English as a foreign language, an art gallery manager besides authoring a range of books.

But as most philosophers were “so preoccupied with thinking about the big stuff — life, the universe and everything — that they seldom gave us the benefit of their wisdom on the little things, the problems of everyday life”, he seeks to remedy this deficiency here in this book.

“So, we can’t be sure exactly of what any philosopher’s answer would be, but we can get a pretty fair idea of the way each thinker would look at the problem,” he says, going on to use ideas of an eclectic group of over 80 philosophers and thinkers from all over history and the world, not only the Western intellectual tradition, for this purpose.

And thus those on call range from Aristotle to Alan Turing, the Buddha to (Simone) de Beauvoir, Confucius to Camus, Machiavelli to Marx, and many more.

Divided into five broad sections — relationships, work, lifestyle, leisure and politics, the questions range from the (relatively) small matters of modern life (what causes addiction to technological devices or the relative merits of Shakespeare and “The Simpsons”) to more vital issues (is it justified to somehow sideline colleagues to a promotion, how can we convey to the government our resentment at its functioning or is it ethical to eat meat) and then the great questions of existence (why are we scared of dying or how can we believe in existence of a benign deity in a world full of evil).

Weeks here does stress that many of these problems are not “specifically ‘philosophical’, but, like almost everything, they can be approached philosophically”.

Some practitioners would use the chance to delve deeper into “hidden implications”, many would “make a connection between the question and their own ideas and theories” and, more often, they will express different solutions and conflicting advice, based on their own outlook and approach.

Given the different avenues that are indicated, the book may be seen as a cross between a freewheeling account of intellectual debates and a sort of “self-help guide” to some of our problems. But as it uses philosophers’ view of the underlying inherent moral problems, causes and likely solutions, it never presumes to offer any direct guidance or indicate which course is best to follow.

For that’s the basis of any good philosophy — indicating the ways but leaving it to us to choose which one is suitable.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: The Knives; Author: Richard T. Kelley; Publisher: Faber & Faber; Pages: 497; Price: Rs 499

There is no shortage of security challenges — terrorism, radicalism, illegal immigration (and the backlash it causes) — for modern nations, particularly in the West. Now imagine you had the responsibility to tackle these. How effective could you be against a backdrop of budgetary cutbacks, political intrigue and a sensationalist media ready to pounce on any lapse?

In the hot seat as Home Secretary, British soldier-turned-Conservative politician David Blaylock discovers being tough himself is not enough, his ministerial colleagues — who include two of Indian-origin — and his bureaucrats can be as devious and covert as his adversaries, whatever he does or doesn’t will invite criticism and there are no easy or evident choices. And his fierce temper that is never below the surface isn’t really helpful.

In his third novel, author Richard T. Kelly serves up an engrossing but portentous tale of modern security challenges in Britain and the political considerations and costs of tackling them.

Opening with a interlude from the Bosnian war, which brought Islamist fundamentalism into Europe with a vengeance and where peacekeeper Blaylock discovers the limitations of armed force, it begins formally 17 years down the line in 2010 when he has abandoned his uniform for a politician’s dark suit.

Entrusted with handling one of the toughest government jobs in a terrorism-menaced milieu, he finds that army life, while dangerous, was better supported. As he thinks one morning that whenever he said anything to his colleagues, “they smiled and nodded, as if they would follow him into the thick of any fight. Somehow, though, whenever he glanced back over his shoulder, he didn’t see them there”.

In course of the next few months, we see our protagonist trying to avoid political pitfalls like being seen as a leadership challenger, fending off ambitious colleagues or subordinates, seeking to win over an obdurate bureaucracy and police miffed over budget cuts, and braving the press which would rather focus on his peccadilloes.

At the same time, Blaylock has to prevent any more terrorist outrages, move forward his desired proposal for a national identity card, which has drawn adverse reaction from various sections, and take flak for “normal” crimes caused by laxity/shortage of law enforcement personnel. Then, to his dismay, the illegal immigration figures are still unacceptably high despite all action as an independent report notes.

Alongside he has to rule on extradition and refugee matters, especially those that have gained wide media coverage, field all sorts of demands from the Americans and identify moderates who can counter radicalism — not only of the Islamist sort.

Adding to the complications are his relations with his ex-wife and children — as she dashes hope of getting back again by disclosing a new love, while Blaylock suspects his boy is linked with a group of anarchist protesters. Then someone close to him is leaking information to media.

It is an uphill fight for someone who is not naturally a part of the establishment, can’t keep his temper in check or surely identify whom he can trust or not.

And as betrayals and setbacks, both personal and political, amass and his temper surges, there can only be one outcome — and it is triggered by what happens around Christmas when Blaylock is not able to meet his children to give them his gifts. But there are still twists ahead as the story comes to its shocking climax.

While Kelly seeks to disclaim his story is based any real circumstances, he does note that “it reflects some matters of public interest in the time it was written” and he has drawn on conversations with politicians, bureaucrats and other stakeholders described here to lend it greater verisimilitude.

Accordingly its pulsating action, suspense and drama is complemented by the political gambits and deal-making and administrative foot-dragging and cost calculations to give a rare, real — but not very comforting — feel of how modern governments operate and face their challenges.

An unparalleled political thriller with a flawed hero, it is a much better representative of its genre than the other sensationalised and over-the-top stuff we are accustomed too.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Himani Kothari,

By Himani Kothari,

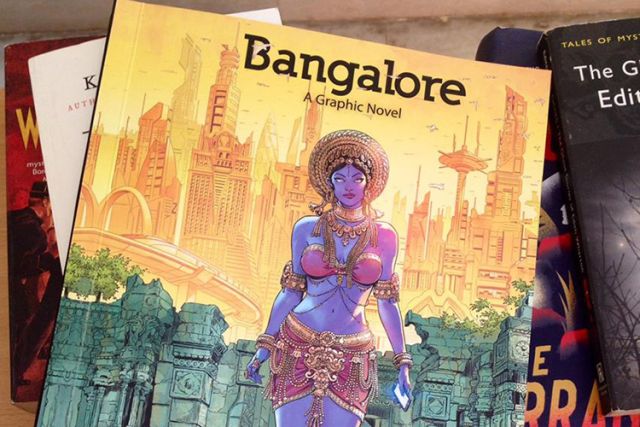

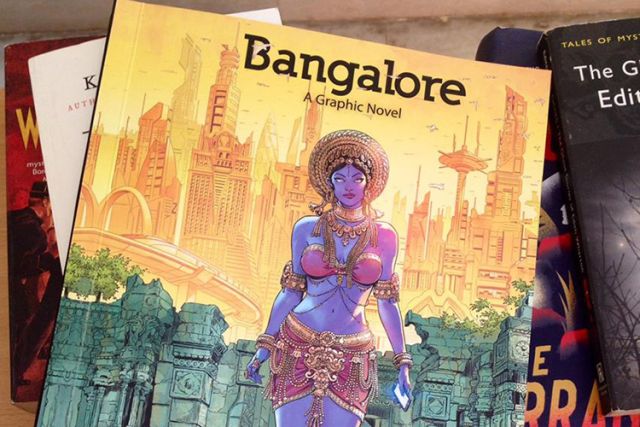

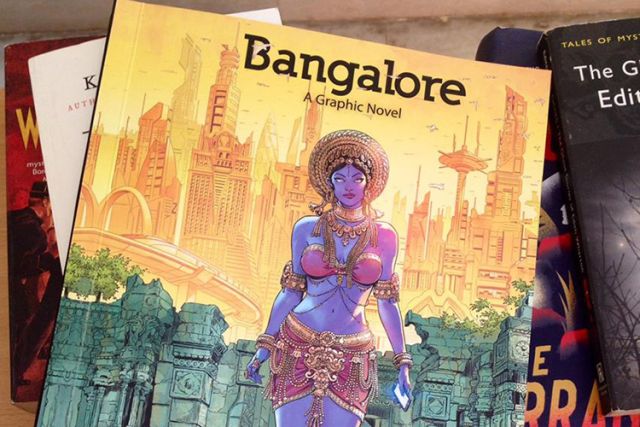

Title: Bangalore: A Graphic Novel; Authors: Various; Compiled by: Jai Undurti & Praveen Vempadapu; Publisher: Syenagiri; Pages: 84; Price: Rs 400

If Bengaluru were a person, it could be like a member of Bollywood’s fabled Kapoor family whose succeeding generations have managed to remain relevant even as times and norms change. But is this gift for perpetual validity all that goes into making the city alluring?

Beyond the shiny glass towers housing established tech giants and new start-ups alike, the heritage of Bengaluru goes back centuries — to even before its formal birth in the early 16th century — and thus defining its history is not easy.

However, 18 artists have come together to try and, in “Bangalore: A Graphic Novel”, to show us what the city means to them. Through their eyes, we see a Bengaluru devoid of its cliches, the Bengaluru of the past, the Bengaluru of the future and the Bengaluru of today.

Most of the nine stories here are dark — both visually and content wise — and exhibit a neo-noir style (reminiscent of the setting of the Sin City movies) with some sort of crime being a common plot device. Harsh tones, striking imagery and masterly use and interplay of colours makes tearing your eyes away to turn the page harder with each panel a work of art.

Some have a more cheerful appearance and are relatable to beyond those living in Bengaluru. Like the nostalgic but bittersweet feeling of returning to your hometown only to see that the landmarks of your childhood no longer exist and that “your friends and family are reminders of what once was”. Or about going back to undo the course of your life — which one of us hasn’t wished to do.

Among the stand-outs is the real story about an African-American sailor who jumps his ship in the early 1900s, and goes on to become the most famous boxer the country had seen at the time.

Author-artist Sumit Moitra’s “The Incredible Story Of Gunboat Jack” is an apt example of how an exciting story can be more frequently found in the unread pages of history, rather than the most fertile imagination.

Moitra, who was born and lives in Kolkata and is a journalist by profession, told IANS that Bengaluru actually “exists in my head” — with experiences of many friends and relatives who have moved there colouring his perception, though he himself spent just a week in the city before getting down to write about it.

Moitra, who admits he doesn’t follow a specific individual style, however said it was important that the art should convey the time period during which the story unfolded and in this a point of reference was the depicted era’s black and white movies.

Squeezing pace and character development in less than a dozen pages was another challenge which he successfully surmounted by his unique presentation, but above all, he managed to depict Gunboat’s state of mind and the “fears and insecurities of an African-American, brought up in an environment of discrimination and racial abuse in the US”, and how he would “approach life in an alien country of brown people dominated by the British”.

And then there is the powerfully unsettling “drive” of the unnamed senior business executive in the Jai Undurti-scripted and Rupesh Arvindakshan-illustrated “Mileage”, which will teach you to be careful while walking on deserted roads late in the night.

The collection opens with Appupen’s stark and uncheering look at a dystopian future in “Bangaloids”, and given the unrestrained and unplanned development, the massive traffic gridlocks and the increasing lack of empathy, the future may not be very far off.

A little more upbeat yet poignant is Ramya Ramkrishnan’s “No More Coffee”. Set in the iconic coffee house where two lonely hearts meet after a crossed order and get hitched — but years later, the woman discovers their union is not what it promised to be. While many others of her kind would — and do — lament their fate, for her, “if I could turn back time” is not only a wistful regret. And all it takes is a shove.

All the entries, different as they may be, go on to coalesce in a glittering kaleidoscope of the city in both its vibrant highs and tragic lows that will appeal to anyone looking for inspired story-telling. Don’t miss it.

(Himani Kothari can be contacted at himani.k@ians.in )

—IANS