by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: The Descent of Man; Author: Grayson Perry; Publisher: Penguin Random House UK: Pages: 127; Price: Rs 499

Fans of the film “Godfather” may recall that scene in the beginning where Don Corleone’s godson Johnny Fontane breaks down while revealing his problems and the exasperated Don gets up and shakes him, bellowing: “You can act like a man.” Good advice? No, but not only because it is from a mafia supremo.

A lot of problems in our modern life, especially in recent times, are arguably man-made — with a stress on the first word. Or rather from the men, conditioned to display a pattern of particular attitudes and behaviour that is “expected” from them for ages.

But this sometimes can have less than salutary effects for people around them.

“Most men are nice, reasonable fellows. But most violent people, rapists, criminals, killers, tax avoiders, corrupt politicians, planet despoilers, sex abusers and dinner-party bores do tend to be, well… men,” says artist, broadcaster and author Grayson Perry.

And in this incisive, persuasive, honest, and above all, witty book, he seeks to understand the root of this problem and what can be done about it, for it can — and does — have dire effects on society.

Ascribing this state of affairs to masculinity, or at least the version presently existing, he says it needs to be questioned but the first step is creating awareness of the problem — or rather, creating awareness that there is a problem.

If you think these are the hyperbolic rants of a feminist sympathiser, Perry, who stresses that he is not against men in general or even all masculinity, takes pains to create a compelling case for his contentions, why the issue needs attention and how men are also its major victims.

“Examining masculinity can seem like a luxury problem, a pastime for a wealthy, well-educated, peaceful society but I would argue the opposite: The poorer, the more underdeveloped, the more uneducated a society is, the more masculinity needs re-aligning with the modern world, because masculinity is probably holding back the society,” he says.

For it is this “outdated version of masculinity” — of seeking power, dominance, or even to be right, of exhibiting strength and ambition — that is leading to crimes, wars, subjugation of women, and economies being “disastrously distorted”. And then, some forms of such masculinity, “particularly if starkly brutal or covertly domineering — are toxic to an equal, free and tolerant society”, warns Perry.

In his account, which blends personal experience, acute social observation — though mainly in the Western context — and analysis, including differentiating between sex and gender, a concept of the “Default Man” and how perceptions of masculinity by both sexes help to shape it, he focusses on four areas of masculinity which he thinks need overhaul, or even expansion with traits usually deemed “feminine”.

These are power, or how men dominate much of our world; performance, or dressing (a particular highpoint) and acting the part of man; violence, and why men resort to it and crime; and finally, emotion, or how they feel.

As Perry elaborates on these, his writing becomes slightly uneven, with the latter chapters not as perceptive as the initial ones, but this is set off by some sparkling, aphorism-like turns of phrase. For instance, “Fulfilment of masculinity is often sold on the strength of peak experiences: Winning battles, pulling women, pure adrenaline, moments of ecstasy. But life ain’t like that.”

A collection of cartoons, a succinct summing-up and, lastly, a “Manifesto of Men’s Rights” (which can fit on a postcard) are further compensation.

Finally, it must be revealed that Perry is a self-confessed, unapologetic transvestite. If this leads you, male reader, to query if he is even remotely qualified to discuss, let alone pass verdict on, such a “male” subject like masculinity, then the book is definitely for you. But do read it with an open mind.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: Red Sky at Noon; Author: Simon Sebag Montefiore; Publisher: Century/Penguin Random House UK: Pages: 416; Price: Rs 699

If you think all the common plots of war novels — the mission behind enemy lines, usually by a bunch of condemned men on their last chance, a love affair between enemy personnel, war’s uncompromising nature, realisation of unsuspected abilities and so on — have been worked to death, here comes a new book spectacularly demolishing this belief.

These tropes of a particular genre don’t change but the way they are presented can, in the pursuit of an enthralling, engrossing story. And Simon Sebag Montefiore, who has been both a historian and novelist of Russia, doesn’t disappoint in his latest novel.

Skillfully combining the carnage on World War II’s Eastern Front, where psychopaths on both sides have a field day, the desperate calculations of the top Soviet and Nazi military commands, the paranoid atmosphere of Stalin’s Kremlin and the near-death existence in Siberian gulags, where criminals hold sway, he offers a tale which is engrossing, hair-raising and in some way, even heartening.

A spirited conclusion to Montefiore’s “Moscow Trilogy” after “Sashenka” (2008) and “One Night in Winter” (2013) — though in plot chronology, somewhere between them — it has as its main strand, the 10-day actual war career of Soviet journalist and author Benya Golden, who plays small but very vital roles in the earlier stories.

In the gulag in sub-Arctic Siberia for nothing else but just knowing the wrong person at the wrong time (as “Sashenka” readers will recall), he has managed to exchange his exacting and doomed existence to an equally lethal position in a “punishment” battalion — a rare Jew among Cossacks, criminals and the odd political prisoner.

As the story begins with Hitler’s armies striking deep into south Russia in the summer of 1942 and the Soviets scrambling to stop them, Golden is on a mission that could lead to his rehabilitation, but it goes wrong from the start.

While most of his compatriots are killed in their first encounter with the enemy — and many others captured, brutally tortured and killed — Golden is saved by a Soviet doctor who has thrown his lot with the Germans and even has some secret Soviet plans for them. The doctor sends him to an Italian encampment for safety.

There, Golden falls in love with Fabiana, a nurse who has lost her high-ranking officer husband recently. She helps him to escape, and at the last minute, decides to go with him. They have an affair while fleeing their pursuers but eventually realise they have to go their separate ways.

Golden, meanwhile, reunited with a trio of his comrades, manages to strike another blow to the enemy. But back in Soviet territory, he learns to his horror that he has committed a huge blunder and must make prompt restitution if he doesn’t want to go back to the gulag.

But can he survive a second trip into the war zone? And what is Fabiana’s fate?

In parallel, runs the account of Josef Stalin overseeing the war with his close associates, such as spy chief Lavrenti Beria and (the fictional) Hercules Satinov, while the third strand is about Stalin’s much-neglected daughter Svetlana, who engages in a love affair with an older journalist which is discovered and ends badly for him.

The book — which makes apt use of historical personages and events both in actual and with artistic license (Montefiore taking care later to clarify which is which) — is, however, not only about war, or how it is rarely as glorious as seen from a safe location or its capability to set new standards in horror and brutality or even Stalinist repression.

Though it has plenty of evocative war scenes (especially cavalry action) but also some harrowing ones of the aftermath, some crisp dialogue and incisive, well-rounded portraits of Stalin and his key associates as well as a cameo of Hitler, it is fundamentally about the humans who fight wars and how their instinct for survival, appreciation for companionship and even love can rarely desert them.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

Book: Trail of Broken Wings; Author: Sejal Badani; Publisher: Lake Union Publishing, Seattle; Price: Rs. 399; Pages: 370

At a time when sordid tales of sexual abuse and wanton chauvinism emerge from Hollywood and other locations, Sejal Badani’s “Trail of Broken Wings” turns the spotlight on how one cannot always view one’s home as a safe sanctuary.

While the Harvey Weinstein saga of abuse has exposed the potential perils of the professional space, Badani, through her novel, speaks of how the four walls of a home can also represent a cage of melancholy and sadism and the roof a thick sheet of sheer oppression.

The book captures the lives of three sisters of Indian origin in America. They have lived their respective lives with a morbid secret buried deep within. As the pages flip, the secrets slip out — perhaps at a slow pace, especially for someone looking for a quick read — long after Badani starts off the story with their father, Brent, slipping into a coma.

Sonya, who has left home at an early age to escape the abuse — both psychological and physical — meted out to her by her father, is called by her mother Ranee to help her tide through the rough time.

Trisha, the youngest daughter — and to the rest of them the father’s pet — is “happily married to Eric, who insists on having children.”

She is also carrying a burden of her own, having seen her sisters suffer both physically and mentally at the hands of their father. But that is not all and there is a secret she has not let out to her siblings.

Marin, the eldest sister and also the most disciplined and successful among the three, too carries within her the seeds of woe — the emotional scars of a near brutal relationship with her father, whose beatings she managed to avoid only by becoming perfect at what she did.

Through the pages Badani weaves in triggers for each of the characters, which add to the twists as well as help build layers of vulnerability around the key characters, including that of the mother Ranee.

For Sonya, it’s a return to a horrid past which she had abandoned for a no-strings-attached existence. Eric’s nagging insistence for a child and slighting of Trisha over the issue breaks her down and makes her dig into her suppressed conscience, making her open up about the time when her father raped her — a fact not known to any of them.

Marin, on the other hand, who has suffered physical abuse at the hands of her father, comes to terms with it when she learns of the physical violence against her teenaged daughter Gia by her boyfriend and the fact that the girl is not resisting the assaults.

But it is the mother’s radical decision, after years in duress-filled marriage, which lends a sense of steely body to the narrative of collective angst of the three sisters.

Recounting Ranee’s role, however, would be unfair and would take away from the read, rather than add to it.

Each chapter is dedicated to individual stories and the perspectives of the four key characters. Despite the slow pace of the book, it churns out a significant level of curiousity and anxiety, if you are equipped to handle the gloom.

(Mayabhushan Nagvenkar can be contacted at mayabhushan.n@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

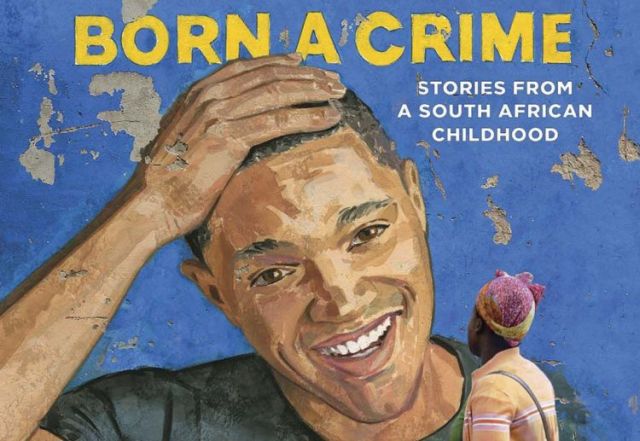

Book: “Born A Crime”; Author: Trevor Noah; Publisher: Hachette India; Price: Rs 399; Pages: 288

The immensely popular host of “The Daily Show” on American network Comedy Central may come across as a funny and startled character but Trevor Noah’s compelling memoir presents a troubled look at life in South Africa under apartheid and is a classic tribute to his mother.

For those who have followed the author’s stand-up comedy acts on television, some episodes that find mention in the book may be familiar. But his memories in the book are not fine-tuned to meet the expectations of television viewers and as such they are more raw, original and appealing to the readers.

In his memoir, Noah takes his readers on a journey to his childhood, being born “a crime” in apartheid South Africa. He reflects on being “half-white, half-black” in a country where his birth “violated any number of laws, statutes and regulations”. Noah was born to a white Swiss father and a black Xhosa mother at a time when such a union was punishable by five years in prison.

The author’s memoir is no comedy like his stand-up acts; it shows the depression and sorrow of what growing up meant for him. He recalls that “the only time I could be with my father was indoors” and that he missed out on a lot of things that he wished to be true during those days.

“If we left the house, he’d have to walk across the street from us,” he writes about his father, but it was equally dangerous even for this light-skinned child to walk with his mother. “She would hold my hand or carry me, but if the police showed up she would have to drop me and pretend I wasn’t hers”.

He didn’t have any friends while growing up as a child and spent most of his time inside the house. “I didn’t know any kids besides my cousins,” he recalls but adds, “I wasn’t a lonely kid — I was good at being alone.” He, therefore, read a lot of books, played with “a toy” that he had and made up “imaginary worlds” in which he lived.

This memoir that initially appears to be a simple story of growing up in South Africa under apartheid is also the story of the mischievous young boy who grows into a restless young man as he struggles to find himself. More than that, it is the story of Noah’s relationship with his fearless, rebellious, and fervently religious mother, a woman determined to save her son from the cycle of poverty, violence, and abuse.

Some anecdotes that he shares of his mother in the memoir, particularly his reflections on things that she told him, are so deep that they haunt the mind of the reader long after the book is closed. They live with you and may even change the way you look at things.

“Abel (his father) wanted a traditional marriage with a traditional wife. For a long time I wondered why he ever married a woman like my mom in the first place, as she was the opposite of that in every way. If he wanted a woman to bow to him, there were plenty of girls back in Tzaneen being raised solely for that purpose. The way my mother always explained it, the traditional man wants a woman to be subservient, but he never falls in love with subservient women. He’s attracted to independent women. “He’s like an exotic bird collector,” she said. “He only wants a woman who is free because his dream is to put her in a cage,” Noah writes.

The mother-son relationship was all he had after his father moved back to Switzerland.

“There was no stepfather in the picture yet, no baby brother crying in the night. It was me and her, alone. There was this sense of the two of us embarking on a grand adventure. She’d say things to me like, ‘It’s you and me against the world.’ I understood even from an early age that we weren’t just mother and son. We were a team,” he mentions.

The best thing about this memoir is the fact that Trevor Noah has a real story to tell — one that is both personal and appealing to readers. On the flip side though, the 288-page long memoir (India edition) is printed in too small a font making it quite a task for readers.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

(Book: The Silent Companions; Author: Laura Purcell; Publisher: Bloomsbury; Price: Rs 599; Pages: 364)

Set in Victorian England, the offering at hand is an extremely creepy and menacing Gothic horror novel. Just released in the Indian market, it is perhaps the most anticipated novel from the horror genre this year at a time when horror and mystery genres seem to have taken a backseat.

The cover of this novel displays far too many objects drawn all around the page — two wolves, a child, an elderly woman, the head of a deer, a cage with a bird locked in it and another empty cage, three other birds, a scissor and an ink pot — and it is quite a task to comprehend the entire picture.

But it is perhaps done to draw your attention to the little hole just above the title of the book. From within that tiny hole is a haunting eye staring right at the reader. You turn the jacket to open the page from where the eye is staring out into eternity and the complete image of a child, dressed in rather unusual clothes, comes to light.

From here on, the reader plunges on to a journey of many discoveries, populated by ghosts all along.

“The Silent Companions” opens with Elsie Bainbridge, mute and medicated in a hospital, recovering from some unspeakable murders of which she is accused. Unable to speak after all that has happened to her, she is encouraged by one of the doctors to write down her story.

The opening scene is impressive and has a larger role in the narrative of the story. It occurs when the protagonist gets married but is widowed equally soon. Bainbridge is then sent to the forsaken estate, originally owned by her husband, to bury him. After the funeral, the turn of events is such that she has to wait for the birth of her baby at the same estate.

A cousin of her husband, Sarah is sent to give her company. Joining the two ladies in this deserted estate are two maids and a housekeeper.

Setting of plays is an extremely important role in any horror novel or movie. Author Purcell deserves full credit in painting a haunted setting before introducing her ghosts in the novel.

The very spread of the mansion is such that the readers have a hundred pictures running across their minds. It is huge and there are few inmates. The local church and the local villagers are surprisingly scared of the estate. The weather is extremely cold and the wind carries with it some kind of a strange smell of lifelessness. Our protagonist hears strange noises night after night. And then there are the “silent companions”, of whom the readers have been warned about in the title of the book. These are full-sized figures painted on wooden boards to resemble children and maids.

These wooden figures are discovered by Sarah and Elsie in a locked attic of the estate. What is most intriguing about these companions is the fact that they have a rather uncanny and strange way of looking at people. For instance, Sarah and Elsie are standing at two opposite ends of the room facing each other. One of these figures appears to look straight into Sarah’s eyes, as if it were to penetrate deep inside and shatter her eyeballs. Just while this is happening, Sarah suddenly notices the eyes of the figure move and she screams in fear.

Elsie is screaming too. Everything that just happened to Sarah happened to Elsie as well.

To make things more creepy, Purcell introduces her readers to some old diaries written about two centuries ago. These describe the horrific events that lead to the start of the Bainbridge family’s downfall. The text in these diaries also form some sort of a link to the series of events that turn our confident young protagonist into a sad and dejected woman that we come across at the beginning of the novel.

The slow and eerie novel takes you step by step before leaving you, along with the protagonist, in the isolated estate with the silent companions. The figures on the cover of the book that confuses the reader in the beginning appears to make complete sense when you reach the end of the novel. It’s a novel you finish in one sitting — on edge and spooked.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS