by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: A Ticket to Syria; Author: Shirish Thorat; Publisher: Bloomsbury India: Pages: 254; Price: Rs 399

Faith can move mountains. But when distorted and misplaced, it can demolish lives, families and much more. And this destructive tendency can even manifest itself in places far away from an area of savage religious strife. Say, an idyllic Indian Ocean archipelago nation, whose people are being drawn into the violent maelstrom of the Arab heartlands.

The Maldives may be a tropical paradise, but there is great trouble afoot for it has emerged as an unlikely, but very fertile, breeding ground for Islamist jihadists.

“Despite its very modest population of approximately 350,000, the Maldives has the highest recruitment percentage when it comes to its citizen leaving to engage in jihad either alongside the Islamic State or the Al Qaeda,” reveals author Shirish Thorat in a factual introduction to this pulsating but disturbing thriller.

And, as he shows, there are no signs that anything serious is being done to tackle this worrying trend at the national level.

But any problem comes more to attention when it is related to actual people, rather than being dealt in abstract terms and that is what Thorat, an Indian policeman-turned-terrorism, money laundering and risk-mitigation expert does in his latest book.

Thorat — who has written a Marathi thriller on 26/11 and, in “The Scout: The Definitive Account of David Headley and the Mumbai Attacks” (2016), co-authored with Sachin Waze, offered a riveting and plausible reconstruction of their preparation and course — also bases this on a true incident he dealt with in his vareer as a security consultant.

“The names, places and sequences of events have been changed for obvious reasons and I leave it to the reader to determine which parts are fact and what is necessarily fiction,” he says.

The story starts with another consignment of mostly eager Islamic State recruits, including a batch of Maldivians, being ferried across the Turkish-Syrian border to the group’s “capital” Raqqa, but its impact comes subsequently.

This is when, back in the Maldives, doctor Sameer Ibraheem, just back from an internship in India, finds all his other siblings — two brothers and three sisters — have, just two days back, voluntarily and surreptitiously left for the jihad in Syria, along with their spouses and infant children.

Also concerned is prominent businessman Ahmed Idris, whose sister Zahi is married to one of Ibraheem’s brothers and is part of the same group. As he and Ibraheem join forces to see what they can do, they find that their government is not only unhelpful but hostile too, and even childhood friends can turn traitors.

But Idris has another card up his sleeve — a “Contact” in the US whom he has seen ably deal with matters like this a few years ago. And then he receives a call from Zahi — who has been taken away on false pretences and had a phone she bought in a whim on the way that the others don’t know about — to seek his help to get her out.

The “Contact” — whom many people who know the author will find familiar — then calls in a series of favours to mount a desperate rescue operation. Will they extract Zahi, who is witnessing some harrowing situations? And what happens when the IS learns of the “Contact” and identifies him as a threat?

Ranging across the deceptive security of the US, the violent Middle East, the Maldives and India, and involving FBI agents, oil-smuggling tanker captains, travel agents who can offer much other than tickets and tours, well-connected Gulf businessmen, jihadist filmmakers, oblivious politicians, unscrupulous preachers and more, Thorat offers an unsettling look into a deadly but much-ignored security issue.

Alongside, there is an incisive but lucid view of Islamist movements and how they found an outcome in the IS, a look into the vested interests which curb eradication of terror and a perceptive look into anti-terror operations.

There are a couple of sticking points — such as the motivations and means behind the efforts by the “Contact”, but, on the whole, it is a terrific, taut story — and a compelling look into an issue that is screaming for attention.

Let’s hope this book does the trick.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: Twilight of American Sanity; Author: Allen Frances; Publisher: William Morrow/Harper Collins: Pages: 336; Price: Rs 799

There are some times you can despair of the human race, or at least significant portions of it. Especially the times when a country that sees itself as a world leader — and many around the globe look up to — seems to have collectively abandoned sanity and ended up with a President who seems something out of a psychology textbook.

We may call Donald Trump crazy but can this suffice to explain his victory in a democratic election, even though it was patently flawed, rigged and vitiated? Or should we look elsewhere, say in terms of that Shakespearean plaint from “Julius Caesar”: “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, But in ourselves…”

How exactly are we to blame is what eminent psychiatrist Allen Frances explains here, arguing that the triumph of Trump represents the ascendancy of the worst traits of humans, bolstered by some less-than-wholesome features that are particularly American.

In this unsettling, bitter but much-needed prognosis, he shows how these have implications beyond Trump — or other global leaders who exhibit one and more of his attributes — or the US, to the course and future of democracy and even our planet.

Frances, deemed one of the foremost experts on psychiatric diagnosis and past leader of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders or the “Bible of psychiatry”, says it may well be comforting to write off Trump as an exception — an extremely egregious one — or crazy, but this tends to hide the real problems.

Recounting how he was invited on TV in the initial days of the Trump campaign, to give his view on Trump’s psychological state, he says he declined for two reasons. Firstly, he had no evidence that Trump had any mental disorder, and secondly, professional ethics disallowing armchair diagnosis of politicians that can be exploited.

Trump is not suffering from a narcissistic personality disorder as several amateur diagnosticians have said, says Frances, who wrote the criteria for it in the DSM, despite displaying its symptoms like grandiose self-importance, having to hang around with special people, requiring constant admiration, lacking empathy, and being exploitative, envious and arrogant.

“… being a world-class narcissist doesn’t make Trump mentally ill”, he says, for this requires clinically significant distress or impairment, but Trump is a “man who causes distress in others but shows no signs himself of experiencing great distress… Trump is a threat to the United States, and to the world, not because he is clinically mad, but because he is very bad”.

And the harsh lesson, he says, is that: “Trump isn’t crazy, but our society is.” While he means the US, the world’s oldest democracy, there is lots that could also strike a chord with our own largest democracy, its dynamics and particularly, its leaders.

In a sweeping narrative that includes his and his family’s own American journey, the crudities of Trump and right-wing forces in the US, the theories of Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud and Theodore Adorno, the example of Martin Luther King, the “selfish gene”, societal delusions and biases, American strengths and shortcomings, incisive political and social analysis and more, Frances shows how democracy is in trouble from those who subvert it for their own selfish, autocratic and whimsical rule.

Before making a compelling case why Trump triumphed and what possibly terrible outcomes it could lead to, he carefully sets the ground. He begins with global problems — overpopulation, environmental degradation, depleting resources, terrorism, inequity — and how US is sidestepping or ignoring them, as well the country’s foreign policy and image of itself.

He then take up the reasons why people end up making such bad decisions on crucial issues with their set of cognitive biases, and “American exceptionalism”.

And while there are barbs aplenty at Trump and the American right wing, the role of social media, some incisive political analysis and a host of telling details — for instance, how the sale of dystopian novels peaked after Trump’s victory — Frances is too professional to just list the symptoms, but also provides prescriptions aplenty for the people.

But how palatable these will be for the people of the consumerist societies in today’s democracies remains to be seen — though doom faces us up close.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vishnu Makhijani,

By Vishnu Makhijani,

Book: 1984 – India’s Guilty Secret; Author Pav Singh; Publisher: Rupa; Pages: 268; Price: Rs 500

The 1984 anti-Sikh riots following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi that claimed the lives of an estimated 8,000 people in Delhi and around the country were not spontaneous as has been made out but were government-orchestrated, says a scathing new book on the four days of mayhem, adding it’s time the world took note of the killings, as it did of the slaughter of a similar number of Bosnian Muslims in 1994.

“At the time, the authorities projected the violence as a spontaneous reaction to the tragic loss of a much-loved Prime Minister. But evidence points to a government-orchestrated genocidal massacre unleashed by politicians — with the trail leading up to the very heart of the dynastic Gandhi family — and covered up with the help of the police, judiciary and sections of the media,” the author writes.

The government of the day “worked hard on its version of events. Words such as ‘riot’ became the newspeak of an Orwellian cover-up, of a real 1984. To protect perpetrators, the most heinous crimes have been obscured from view; evidence destroyed, language distorted and alternate ‘facts’ introduced. The final body count is anybody’s guess”, the author says.

And yet, “what may well go down in history as one of the largest conspiracies of modern times is hardly known outside of India. At that time, Western governments toed the line of their Indian counterpart and downplayed events — arguably for fear of losing trade contracts worth billions — to the misnomer of ‘communal riots'”, the author says.

Pointing to a meeting held at the residence of then Information and Broadcasting Minister H.K.L. Bhagat on the evening of October 31, hours after Gandhi was assassinated, and attended by an Additional Commissioner responsible for the capital’s Central, North and East districts, and the SHO of the Kalyanpuri police station, all of which bore the brunt of the violence, the author, writes: “The foundation of their plan had, however, been laid well in advance and were in part the outcome of years of suspicion, misgivings and disagreements between the Centre and the state and its political, economic and social demands as framed by the Akali Dal, the governing Sikh-centric party in Punjab.”

“It is believed that key players in the Congress government used the increasingly volatile situation in Punjab to blur the perception of the Sikh community in the eyes of their fellow citizens… These poisoned sentiments gathered such deadly momentum that the execution of Operation Bluestar in June 1984 was regarded by some as ‘inevitable’,” writes Pav Singh, a member of the Magazines and Books Industrial Council of Britain’s National Union of Journalists who has been campaigning on the issue for a number of years.

To bolster the insinuation that the Sikhs’ desire for regional autonomy posed a national threat, the government commissioned a series of documentaries in early 1984. Mani Shankar Aiyar, Joint Secretary to the Government of India, was said, by an associate, to have claimed that “he was given the unpleasant job of portraying Sikhs as terrorists”. He was on some special duty with the Minister of Information and Broadcasting. The minister in question was none other than Bhagat, the book says.

Pointing to an elaborate cover-up of the four days of mayhem, the author says a key figure in the deception was Home Secretary M.M.K. Wali.

“At a press conference on 1 November, he insisted that most of the violence consisted of arson and that few personal attacks had occurred — in what seems an outrageous statement he even claimed that only two people had been confirmed killed in New Delhi.

“He revised the figure to 458 on Nov 4 soon after being sworn in as Delhi’s new lieutenant governor. The Indian Express had reported on Nov 2 that in two incidents alone there were 500 dead, including 200 bodies lying in a police mortuary and at least 350 bodies on one street in East Delhi,” writes Pav Singh, who spent a year in India researching the full extent of the riots.

His research led to the pivotal and authoritative report “1984 Sikhs’ Kristallnacht”, which was first launched in the UK parliament in 2005 and substantially expanded in 2009. In his role as a community advocate at the Wiener Library for the Study of Holocaust and Genocide, London, he curated the exhibition “The 1984 Anti-Sikh Pogrom Remembered” in 2014 with Delhi-based photographer Gauri Gill.

The book is highly critical of the manner in which subsequent governments have acted.

Figures released in 2013 show that of the 3,163 people arrested in the capital, just 30 individuals in approximately as many years, mostly low-ranking Congress party supporters, had been convicted for killing Sikhs. This represents less than one per cent of all those arrested, the book says.

“Out of those arrested, a staggering 2,706 were subsequently acquitted. Convictions for riot-related offences amounted to 412. One hundred and forty-seven police officers were indicted for their role in the killings, but not one officer has been prosecuted. Nobody has ever been prosecuted for rape,” the book says.

It’s time India and the world called a spade a spade, the book says in its conclusion.

(Vishnu Makhijani can be contacted at vishnu.makhijani@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

By Mayabhushan Nagvenkar,

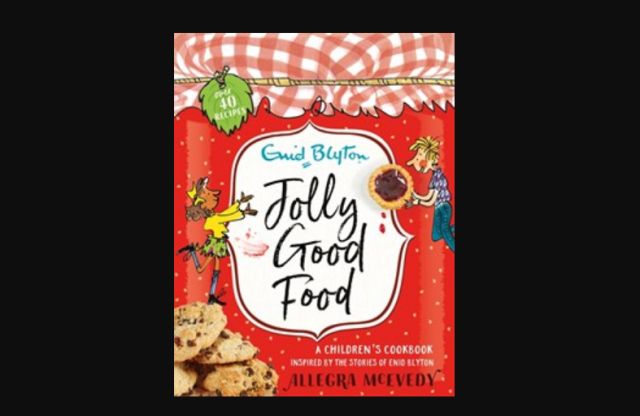

Book: Jolly Good Food; Author: Allegra McEvedy; Publisher: Hodder Children’s Books; Price: Rs. 799; Pages: 133

Enid Blyton knew her mysteries. She also knew her muffins and meringues.

In “Jolly Good Food”, Allegra McEvedy — chef, author and also co-founder of healthy fast food chain Leon — decodes the quintessential and mouth-watering treats littered in Blyton’s classic mystery series like the Famous Five and Secret Seven and brings them alive in the form of a recipe book interspersed with excerpts from the writer’s novels, where the protagonists pack their wholesome hampers or gorge on piping hot muffins or slosh down homemade lemonade all in the midst of solving mysteries and unearthing secrets in Britain’s suburbs or the countryside.

Neatly packed in 133 pages, complete with sketches and images, the hardbound book spells out more than 40 recipes, which break down the sumptuous food and drink that Blyton’s immortal characters have gorged on as fuel for their curious minds, keen on cracking the next puzzle.

Predictably, it’s all about traditional British snacks, which face a serious challenge from other world cuisines as well as those from the European continent. While Blyton’s books were elaborate and descriptive about the adventures and curiosities of the young, the mention of snacks, food and beverages, though inevitable, were limited to the finished product and the joys of consuming it. McEvedy attempts to fill this gap of sorts by conveying to fans of Blyton and good food about what goes into making treats like scones, apple tea, jam tarts and quiches.

The recipes are spread across six parts. Each part is dedicated to treats mentioned in six novels (or series), namely, “The Naughtiest Girl in School”, “The Secret Seven”, “Famous Five”, “The Faraway Tree”, “The Secret Island” and “Malory Towers” with beautiful illustrations by Mark Beech.

The six novels are some of the most popular works of Blyton, whose 600 books and over 500 short stories have been published in nearly 500 million copies, devoured by children and adults over generations and across continents.

The book’s third section opens with a passage, “Five Get Into Trouble”, where Julian, Dick, George, Anne and their pet dog Timmy stop at a store in a village called Manlington-Tovey and where Blyton’s technique of weaving food into fiction is best explained. The Five need a cooler and just as the doctor ordered, the store sells ice creams, lemonade, orangeade, lime juice, grapefruit juice and ginger beer. Timmy, at the insistence of his keeper George, also has an icicle as his share of refreshment.

In her recipes for this section, McEvedy includes a detailed recipe for ginger beer just the way the Famous Five love it. A few paragraphs later, Anne wonders whether a cow munching grass in the countryside isn’t tired of eating tasteless grass, when there’s egg and lettuce sandwiches, chocolate eclairs, boiled eggs and ginger beer that can be had. In response, George fantasises about the spread which her mother has laid out for lunch and includes egg and sardine sandwiches and some more ginger beer. Later, Timmy’s taking off after a rabbit in a meadow makes the Famous Five lust for a mouthwatering rabbit’s pie.

Blyton’s infusion of food in this short passage is complete with George offering Timmy raw meat sandwiches which has been packed as picnic lunch.

Blyton’s books will always be remembered by all who read them for instilling a sense of curiosity and innocence to the spirit of adventure. McEvedy’s intervention will now add t

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Himani Kothari,

By Himani Kothari,

Title: The Nothing; Author: Hanif Kureishi; Publisher: Faber & Faber; Pages: 167; Price: Rs 599

Hanif Kureishi is growing old. So are his heroes. The author, who gave us great stories like “Intimacy” and “My Son the Fanatic”, has come up with “The Nothing”, whose protagonist, Waldo, is a once-celebrated filmmaker bogged down by age and illness. Why should we be interested in him?

Waldo, also the narrator of the Pakistani-origin British author’s eighth novel, used to once hang out with the Who’s Who of Hollywood. Now in his 80s, he is a wheelchair-bound has-been, confined to his London home with illness. He is taken care of by his young and devoted wife Zee, short for Zenab. But even in sickness, Waldo is addicted to sex. The only problem is he is impotent.

The novel’s evocative beginning — “One night, when I am old, sick, right out of semen, and don’t need things to get any worse, I hear the noises again. I am sure they are making love in Zenab’s bedroom, which is next to mine” — sets the tone. Dark-humoured, resentful and unpleasant.

The man Waldo suspects Zee is cheating on him with is Eddie — a freeloader and a leech whom he has known for decades but as “more than an acquaintance and less than a friend”.

This gives Waldo’s meaningless life a mission. He wants Zee back and Eddie gone. So he starts plotting and “directing” their lives like one of his films. His desire to mean something, to not be nothing, is what forms the core of the novel.

The level of honesty with which the 63-year-old author has explored old-age sexuality, male insecurity, and the futility of it all, is unsettling.

Let’s be honest, Waldo is a manipulative, scheming, insecure and a vengeful control freak — in short an unpleasant man — and it’s hard to feel any empathy for him. Considering that was the intention, for he was chosen to be the narrator and not Zee, Kureishi failed. But maybe that’s what the author wanted for Waldo — to be loathed and resented — because does the hero have to be likeable always?

While deciding to get Zee back, Waldo muses: “Even these days, a woman is the ultimate luxury; a diamond, a Rolls-Royce, a Leonardo in your living room.”

We live in a politically correct world where even a hint of sexism is sure to cause a Twitter storm and invite trouble — well deserved. To write, in such times, about the desires of a misogynist is brave. It is also important, for writing, like any other art form, should not be subjected to a censor, moral or otherwise.

But Waldo is not just a misogynist; he is also a narcissist and a “lookist”, for whom appearance matters most. Looking back at his youth, when he had “f***ability”, Waldo says: “If you’ve once been attractive, desired and charismatic, with a good body, you never forget it. Intelligence and effort can be no compensation for ugliness… the beautiful are the truly entitled.”

And Waldo can also be pretty crude in his words — with Kureishi pulling no punches with his use of earthy language. As our hero says: “If my suspicions are correct, I will move like a serpent between the rocks… First I will smite him with madness, blindness and impotence… then I will urinate in his mouth and wipe my a** with his head.”

If there is one place where one can appreciate the hedonistic Waldo, despite his insistence on not letting his still young wife (22 years his junior) fall in love with someone else, is his desire. As we grow old, we lose the will to live. But not Waldo. In spite of his flaws, he loves Zee and believes he knows better. It’s this rather self-indulgent belief, generally reserved for artistes, that perhaps made Zee fall for him in the first place.

Does Waldo succeed in his aim of displacing Eddie? Will he regain Zee? And what — and how long — is his future?

So how does “The Nothing” rank? Compared to the Kureishi of “Intimacy” and “The Buddha of Suburbia”, it reads like a lazy work. Like he doesn’t care any more what people think of his art.

There’s a line in the novel where Waldo says: “As a reader, I’m done with literature. I only want fun.” And that’s what Kureishi does with “The Nothing”.

(Himani Kothari can be contacted at himani.k@ians.in)

—IANS