by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: The Mysterium: Unexplained and Extraordinary Stories for a Post-Nessie Generation; Author: David Bramwell & Jo Keeling; Publisher: Brewers/Hachette India; Pages: 256; Price: Rs 699

The human brain can exhibit a curious duality. On the one hand, we generally prefer to understand everything that we face and know the reasons for what happens, and on the other, we relish the mysterious, the inexplicable and the uncanny. And there is a lot of it beyond the fervent desires of the most imaginative.

Gone are the days we were content with trying to find out if the Loch Ness monster actually existed (or in other places, Big Foot or the Abominable Snowman), or aliens regularly visited us, or whether a shadowy cartel actually runs the world. In the contemporary era, there are many other strange, weird and spooky mysteries we are unable to solve despite all our technological development.

“Nowadays, many of us feel nostalgic for a more innocent age when we pored over compendiums of ‘the unexplained’… Their ‘endless search for answers’ immersed us in fantastical tales of prophesy and atmospheric oddities, and blurry photos of Nessie, Big Foot and flying saucers.

“But while a lack of credible proof in our digital age casts doubt over such stories, the universe is as mysterious to us now as it was for our predecessors,” say Bramwell, a radio presenter and author, and Keeling, a journalist-cum-author, in this book — their second after “The Odditorium”, featuring some “tricksters, eccentrics, deviants and inventors whose obsessions changed the world”.

“Over the next 240 pages, we’ve curated 40 truly compelling mysteries, oddities and remarkable tales for the digital age — from the modern-day powers of placebo to Hikikomori, which sees a million Japanese youngsters withdrawing from human contact,” they say.

These mysteries also range from the shadowy inventor of Bitcoin to the shoes — with human feet inside — washing up on a part of Canada’s Pacific coast. There are the cats that can predict human death and those that led political parties to the creepy CCTV footage of a Canadian girl before she went missing.

Bramwell and Keeling also contend that part of the mysteries may owe to the dazzling inventions that seem inescapable part of our lives in this day and age. “While ancient mysteries used to take root and grow organically, passed through generations through storytelling, now we are globally connected. Far from debunking the unknown, the Internet has become a breeding ground for new enigmas. Technology gives mystery renewed strength; stories escalate quickly.”

And they give some telling — and disturbing — examples, especially of an Internet-created ghoul which started claiming real-life victims.

The 40 stories, dealing with mysteries, both natural and man-made, are divided into seven sections. “Strange Fruit” includes such oddities as people and places that don’t exist but are featured in reliable guidebooks — and why. “Ghosts in the Machine” takes up the stories of the monster that jumped from Photoshop into our nightmares, Satoshi Nakamoto of Bitcoin fame, and the personal classified ad that inspired a cult horror film.

“Are We Not Human?” tells of the strange worship of the British Queen’s consort, “Strange Sounds and Spooky Transmissions” has stories of ghost radios, strange humming, the world’s worst orchestra, as well as singing sand dunes, and “Supernature” deals with ball lighting (remember Tintin’s “The Seven Crystal Balls”), celestial phenomenon that has — and could again — cripple our vaunted communication networks, and a “Bermuda Triangle” in space.

But “Mind Games” is among the best, specially the expositions on “Operation Mindfuck”, “Roko’s Basilisk” and the men who scared themselves to death, while the collection ends with “the really creepy stuff” about the detached feet’s landfall and the girl’s mysterious disappearance.

Like the authors’ previous work, this book, written in a dryly witty and non-judgmental manner, informs and, above all, intrigues with the strangeness of our world, which only seems certain to increase.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

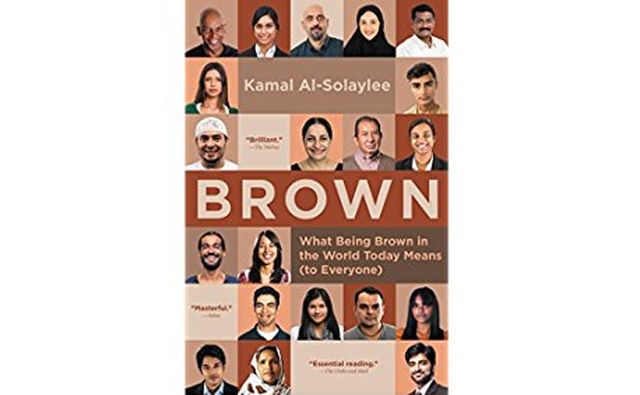

Title: Brown: What Being Brown in the World Today Means (to Everyone); Author: Kamal Al Solaylee; Publisher: Harper Collins Publishers; Pages: 344; Price: Rs 599

All our social development and our technological advancements don’t seem enough to eradicate our long-persisting atavistic sense of difference based on appearance, which though long-suppressed is now emerging free from its restraints — as proved by the recent intemperate comments by US President Donald Trump on immigrants from a certain set of countries.

Trump’s thinking, as seen in his off-the-cuff remarks, underscore that the questionable classification of race, expressed by the obviously evident and inescapable feature of a person’s skin, is well alive — and extends beyond the white-black binary. What about the yellow, or rather, the (as necessary for global economy but far more exploited) brown?

Trump is only one leading manifestation of the malaise facing brown people — which include West Asians, Latin Americans, North Africans, and South and Southeast Asians — and far beyond the West too or from the “Whites”, says Yemeni-origin, Egypt-bred, Canadian journalist-turned-academician Al Solaylee in this book.

Trump’s victory “largely (but not exclusively)” rode on demonising Mexicans, galvanising sentiment against Muslims and championing white nationalism, the vote for Brexit was mostly pioneered by those with a restrictive view of Englishness, the record of Canada under Stephen Harper’s Conservatives — all these are obscure racial conflicts brewing in the US and Europe for decades now.

“Examine these tensions closely and you’ll find a strong anti-brown sentiment at the core,” says Al Solaylee as he traces the response to, as well as the experiences of, the residents of Global South, who are forced to migrate to — and much needed in — the Developed North for various reasons, not least of which is the latter’s colonial record.

“Brown as the colour of cheap labour continues on a global scale… brown bodies undertake the work that white and older immigrant Americans refuse to do (and that black slaves were forced to do in previous centuries). These are low-skill, labour-intensive jobs in unforgiving climates,” he says, but also that these are not limited to the Western nations but also in the more affluent parts of Asia itself too.

“This is now our destiny as brown people. Our labour is needed, but citizenship is denied; our presence as Muslims or religious minorities is offered as an example of the tolerant, diverse societies in which we live, but we continue to be feared,” says Al Solaylee.

And there is no difference whether this is deliberate or mistaken as he goes to cite the cases of the racist slurs on Sikh volunteers feeding the homeless in Manchester in the wake of the May 2017 terror attack, or the fatal shooting of Indian techie Srinivas Kuchibhotla in the US in February 2017 by an American who thought he and his friend were Iranians and screaming at them to “get out of his country”.

Al Solaylee contends we think of brown as a “continuum, a grouping — a metaphor, even — for the millions of darker-skinned people who, in broad historical terms, have missed out on the economic and political gains of the post-mobility, equality and freedom”. They are now living, he says, among former colonial masters where they are “transforming themselves from nameless individuals with swarthy skins into neighbours, co-workers and friends”.

And it is their story he tells — both in their homes from the Philippines to Sri Lanka and workplaces from Hong Kong to the Gulf as well as Western Europe and North America.

Al Solaylee, however, starts with first recounting his own childhood experience on learning he is brown after seeing a English movie featuring a white child and coming to terms with “brownnes”” in his journeys around the world and interactions with other browns (fairness creams figure largely as well as the concern that he settle down) as well as brown’s significance in nature and culture.

He then takes up the human obsession with race, despite the concept being debunked, except in politics before his exploration of the experiences and consequences of being brown around the world.

A stirring travelogue, incisive social and political comment and a passionate cry to rise above unavoidable consequences of geography and genes, this invaluable work rises in importance beyond its subject to be a seminal guide to the world today — and what it will soon be — particularly the US.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Biswajit Choudhury,

By Biswajit Choudhury,

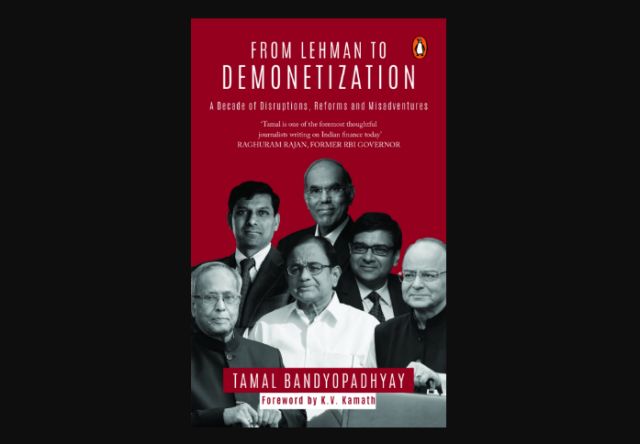

Book: “From Lehmann to Demonetisation: A Decade of Disruptions, Reforms and Misadventures”; Author: Tamal Bandyopadhyay; Publisher: Penguin Random House India; Pages: 348; Price: Rs 599

While last year saw three valuable contemporary insights into Indian banking — two by former Reserve Bank of India Governors and a brilliant short history of the RBI by economic journalist T.C.A Srinivasa Raghavan — a gap, from the perspective of commercial banks in the country, now stands as competently filled by another journalist, Tamal Bandyopadhyay with “From Lehmann to Demonetization: A Decade of Disruptions, Reforms and Misadventures”.

In writing on banking and finance and about the expansion of private banks, Bandyopadhyay — who has earlier written on how Bandhan became a universal bank and on the Sahara scam — devotes a part of this book to the historic points of friction between the government and the RBI. The discussion on political economy then takes him inevitably to dwell briefly on the single-most disruptive measure since Independence, of demonetisation, to which the other authors made only passing references.

The Lehmann in the title refers to the 2008 US financial crisis, the damaging impact of which the globalised world is slowly still recovering from. Meanwhile, anti-globalising trends have taken shape on both Atlantic coasts and are deepening across Europe, while there is a twist to all this with countries like India and China becoming the vocal votaries of globalisation.

India rode the world economic slowdown unleashed by the collapse of US banks better than most others, also because of the financial system being insulated by the RBI, as well as on the strength of the country’s macroeconomic fundamentals. “A cautious and conservative regulator ring-fenced the Indian banks by not allowing them to take excessive risk,” the author notes.

The book begins with a vivid chronological description of the crumbling world of a young finance professional in Mumbai following the colllapse of Lehmann Brothers in the US in September 2008.

A collection of columns and interviews that Bandyopadhyay has published in the Mint, “From Lehmann to Demonetisation” goes to the heart of an issue at the centre of Indian finance now, but the roots of which go back to the boom period in the economy during the last decade under United Progressive Alliance (UPA) rule — the problem of accumulated non-performing assets (NPAs), or bad loans, in the Indian banking system that have reached the staggering level of nearly Rs 9 lakh crore. Only the bad loans of state-run banks add up to around Rs 7.5 lakh crore. NPAs are a major factor in the falling levels of private investment, and coupled with highly leveraged corporate balance sheets, are holding up higher growth in the Indian economy.

“Simply put, Indian banks are caught in a vicious cycle: They are not willing to lend for fear of adding to bad assets; this dents their interest income and profitability; and that, in turn, further erodes their ability to lend as they are not able to plough back profits to bolster their capital,” Bandyopadhyay writes.

On the choice of ways to deal with the situation, he says the banks prefer to restructure loans about to turn bad and not write them off as this would hit their balance sheets. So a CEO prefers to deal with the issue in a denial mode and keep making profits till the successor chief executive starts the “clean-up.”

“Ironically, the new CEO too leaves behind the same legacy for his successor when he retires,” which tendency the author likens to the “saas-bahu syndrome” in the Indian family, where the new bride, on getting older, gives the same ill-treatment to her daughter-in-law that she had received from her monther-in-law.

Some public sector banks have been in denial mode on their NPAs till previous RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan “drove the first-of-its-kind asset quality review (AQR) for these banks”, to reveal the true picture on their bad loans. On the other hand, the regulator has become more “adventurous” about permitting private banking, which have much lower NPAs. “And then, suddenly we got approval for 23 banks in two years since August 2015 — two universal banks, 10 small banks and 11 payments banks,” Bandyopadhyay writes.

In June last year, the RBI referred 12 accounts, totalling about 25 per cent of the gross NPAs, for resolution under the new Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC).

The government has embarked on a two-pronged strategy on bad loans. On the one hand, it has brought in the IBC which provides for a six-month time-bound insolvency resolution process. On the other hand, it has approved a Rs 2.11 lakh crore recapitalisation plan for state-run banks. Rating agency Crisil says banks will need to take a haircut of up to 60 per cent on their bad loans to resolve the NPAs. According to the author, besides the massive government recapitalisation, public sector banks need to raise over Rs 1 lakh crore from the markets to meet capital requirements.

The second part of “From Lehmann to Demonetisation” contains the profiles of 15 people who “exemplify the transformation of the Indian financial sector in the past decade”. These include regulators, professionals-turned-entrepreneurs, investment bankers and a fund manager, and provides a glimpse into the personal side of these “seminal leaders”.

A must-read for students of Indian finance, written in a style that the BRICS Bank Chairman K.V. Kamath describes in the foreword as “witty, pithy, sharp and tongue-in-check — all at the same time”.

(Biswajit Choudhury can be reached at biswajit.c@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Vikas Datta,

By Vikas Datta,

Title: Austenistan; Author: Laaleen Sukhera (editor); Publisher: Bloomsbury India Publishers: Pages: 288 Price: Rs 350

The heroines, living (or aspiring) to settle into stately homes in the class-conscious society of Regency Britain, as we meet in classical literature, may seem far distant in time, space and social mores to their contemporary counterparts in metropolitan Pakistan. But what if they turn out to be sisters under the skin?

Could Elizabeth Bennet (of Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice”), or even her mother, have their equivalents in Islamabad, or Lady Susan (the heroine of Austen’s eponymous novel) be as likely to be found in Lahore as London? And then to be gender-balanced, can Darcy Fitzwilliam only thrive in English climes?

Quite possibly, for “it is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife”. Pakistani women — and their mothers and close friends — know this truth very well, as Laaleen Sukhera and her Pakistani (and one Sri Lankan) collaborators show in this anthology.

The reason for Austen’s global popularity is not so difficult to ascertain given she was writing about women’s dependence on an advantageous marriage for social standing and economic security, but also not negating love fully — which can be seen in patriarchal societies, like in the South Asian subcontinent.

As Caroline Jane Knight, a descendant of Jane’s brother and founder of the Jane Austen Literacy Foundation, notes, in the foreword, that in “some countries readers experience similar predicaments to the women in Jane’s novels, with limited rights, independence and earning opportunities”. “Others can relate to the social norms and family expectations around the finding of a suitable husband!”

While these are universal sentiments that readers may find familiar, credit goes to Sukhera, a Lahore-based media professional and founder of the Jane Austen Society of Pakistan, for adapting these immortal classics to “desi” conditions and sensibilities.

“Pride and Prejudice” takes the lion’s share, inspiring five of these seven stories — identified for readers who have not read or forgotten Austen, with a telling quote from the work in question. Also, Sukhera and the others also work in digital devices, social media, and other appurtenances, that life now seems incomplete without, to evoke a modern sensibility.

Lahore-based magazine editor and freelance journalist Mahlia S. Lone starts with a close approximation of “Pride and..” in “The Fabulous Banker Boys” which has, as its heart, a family matriarch’s attempts to arrange suitable matrimonial alliances for her brood. The point of view shifts to her second daughter Elisha, who has “bucket-loads of independence, spirit and a strong personality”, at a high-profile wedding they are attending where the targeted suitor, the proud-seeming Faiz Dar (the name is indicative) steps in to save her young sibling from an unsavoury situation.

“Pride..” also underlies “Only the Deepest Love” of Lahore-based freelance journalist Sonya Rehman, with some typical — and not so typically exclusive — Pakistani motifs and a range of twists down till the end. It also inspires the poignant “The Autumn Ball” by Sri Lankan scientist Gayathri Warnasuriya, which moves closer to Austen territory by including a ball instead of the Bollywood-bhangra dances in the rest, though the event doesn’t go the way its protagonist Maya may have liked.

Pakistani-American Nida Elley’s “Begum Saira Returns” is a sensuous adaptation of “Lady Susan”, with bittersweet motifs of loneliness and second opportunities for love for a not-so-old widow, and so is economist Mishayl Naek’s “Emaan Ever After”, a take on “Emma”.

But standing out — and both “Pride..”-inspired — are barrister Saniyya Gauhar’s hilarious but heart-warming “The Mughal Empire” about a high society doyenne left in the cold when her brother’s best friend (whom she had her eye on) marries a social climber, and Sukhera’s own “On the Verge”, which takes a society event blogger into Austen’s own territory — a English manor house — where she meets a “Prince Charming” she never expected.

Packed with high society weddings, supportive friends (both male and female), manipulative relatives and rivals, and a gamut of bon mots on contemporary Pakistani life, like “socialising in Islamabad is dead by boredom” and “Being thirty-two and divorced in Karachi requires your dermatologist and personal trainer on speed dial”, this is a work that is not only a tribute to Jane Austen, but literature at its most inspired. Thus, it will not only appeal to more than just her fans or romance aficionados.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

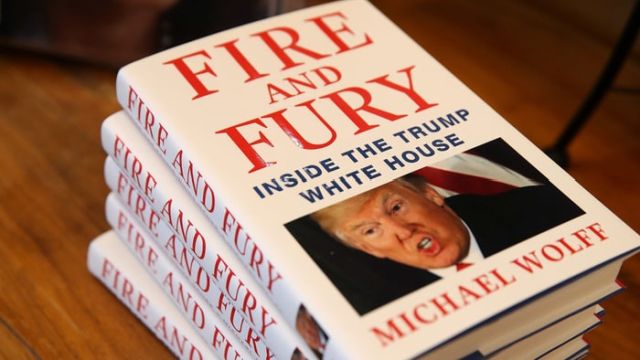

Book: Fire and Fury; Author: Michael Wolff; Publisher: Hachette India; Pages: 320; Price: Rs 699

“A f**king idiot”, “A f**king moron”, “A child”, “A dope” and “Dumb as shit” are some of the descriptions of US President Donald Trump by White House staff in a new book, which the President himself dismissed as “a Fake Book, written by a totally discredited author”, while also directing his legal advisers to prevent its publication. The lawyers failed, but their efforts led the book instantaneously to the top of the bestseller charts.

“Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House”, by Michael Wolff, was originally published by Little, Brown Book Group and has just hit the stands here through Hachette India.

The book begins on an interesting note, explaining what Trump’s team and Trump himself planned to do if he were to lose the elections. The author, who has interviewed many White House staffers and members of the Trump team, contends that Steve Bannon “would become the de facto head of the Tea Party movement”, Kellyanne Conway “would now be one of the leading conservative voices on cable news”, Reince Priebus and Katie Walsh “would get their Republican Party back”, Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump “would have transformed themselves from relatively obscure rich kids into international celebrities”, and Melania Trump “could return to inconspicuously lunching”.

And as far as Donald Trump was concerned, the author says, he would become “the most famous man in the world” and would later launch Trump TV, a network by him, about him, and for the millions of people he thought he understood better than the Republican Party.

Wolff has devoted quite a long portion of the book to studying and analysing Trump’s campaign and reaches the conclusion that it was some sort of a racket, aimed at scoring money from rich guys with big egos. Ironically, according to the author, even the members of his team were not confident of tasting success.

“Almost everybody in the campaign, still an extremely small outfit, thought of themselves as a clear-eyed team, as realistic about their prospects as perhaps any in politics. The unspoken agreement among them: Not only would Donald Trump not be President, he should probably not be. Conveniently, the former conviction meant nobody had to deal with the latter issue,” Wolff writes.

But that is not all. The author claims that most of the problems of the Trump administration today are a direct result of its weak foundations. He raises some serious questions in the book: Why release your tax returns if you’re never going to win? Why not collude with the Russians if you are more likely to build a hotel in Moscow than occupy the White House? Why focus on policies related to education and public healthcare if you are never going to win?

And what after winning the election? “What was, to many of the people who knew Trump well, much more confounding was that he had managed to win this election, and arrive at this ultimate accomplishment, wholly lacking what in some obvious sense must be the main requirement of the job, what neuroscientists would call executive function. He had somehow won the race for President, but his brain seemed incapable of performing what would be essential tasks in his new job. He had no ability to plan and organise and pay attention and switch focus; he had never been able to tailor his behaviour to what the goals at hand reasonably required. On the most basic level, he simply could not link cause and effect,” writes the author.

The key point rising out of “Fire and Fury…” is not that Trump’s ignorance is about absence of knowledge but rather that ignorance is a part of his personality, and that scares Wolff.

The author quotes an internal White House email, apparently representing the views of Gary Cohn — Trump’s chief economic advisor — to establish this point: “It’s worse than you can imagine. An idiot surrounded by clowns. Trump won’t read anything — not one-page memos, not the brief policy papers; nothing. He gets up halfway through meetings with world leaders because he is bored.”

The book has its limits, nonetheless and the most important one is that it is based on very few sources. There seems no effort to have a counter perspective or account from somebody who does not share the same views about Trump.

Wolff’s primary source for the book is Steve Bannon, Trump’s former chief strategist — many of the chapters proceed from his perspective, and the book ends when he leaves the White House.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS