by admin | May 25, 2021 | News, Politics

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

New Delhi : Special SIT court judge P.B. Desai “ignored evidence” that former Congress MP Ehsan Jafri, who was killed in a mob attack in Ahmedabad’s Gulberg Housing Society during the 2002 riots, did all that was possible within his power to protect Muslims from the “rage of the mob” and instead echoed the position of then Chief Minister Narendra Modi that his killing was only a “reaction” to his “action” of shooting at the mob, says human rights activist Harsh Mander.

He says that “the learned judge”, who retired in December 2017, overlooked statements by surviving witnesses that Jafri made repeated desperate calls to senior police officers and other persons in authority, “including allegedly Chief Minister Modi”, pleading that security forces be sent to “disperse the crowd” and rescue those “against whom the mob had laid a powerful siege”.

Mander, who quit the IAS in Gujarat in the wake of the riots, makes these observations in his just released book, “Partitions of the Heart: Unmaking the Idea of India”, published by Penguin.

The 66-year-old activist, who works with survivors of mass violence and hunger as well as homeless persons and street children, goes on to quote the late journalist Kuldip Nayar to establish that Jafri had desperately telephoned him, “begging him to contact someone in authority to send in the police or the Army to rescue them”.

Mander says Nayar rang up the Union Home Ministry to convey to it the seriousness of the situation. The Home Ministry said it was in touch with the state government and was “watching” the situation. Jafri called again, pleading with Nayar to do something as the mob was threatening to lynch him.

In the chapter titled “Whatever happened in Gulberg Society?”, Mander contends that Jafri did everything within his power to protect “those who believed that his influence would shield them from the rage of the mob”. Mander says Jafri begged the mob to “take his life instead” and in a show of valour went out “to plead and negotiate” with the angry crowd.

“When he realised that no one in authority would come in for their protection, he also did pick up his licensed firearm and shoot at the crowd…,” Mander notes, describing it as the “final vain bid” on behalf of Jafri to protect the Muslims in the line of fire.

The author notes that in describing Jafri’s final resort to firing as an illegitimate action, the judge only echoed the position taken repeatedly by Modi, who had given an interview to a newspaper in which he had said that it was Jafri who had first fired at the mob.

“He forgot to say what a citizen is expected to do when a menacing mob, which has already slaughtered many, approaches him and the police has deliberately not responded to his pleas,” says Mander.

He says that it was as if even when under attack and surrounded by an armed mob warning to slaughter them, “and with acid bombs and burning rags flung at them”, a good Muslim victim should do nothing except plead, and this would ensure their safety.

Ehsan Jafri’s wife Zakia Jafri, according to Mander, was firmly convinced that her husband was killed because of a conspiracy that went right to the top of the state administration, beginning with Modi. The author notes that the court, in its judgement running into more than 1,300 pages, disagreed.

“It did indict 11 people for the murder but they were just foot soldiers,” observed Mander.

He further says that the story the survivors told the judge over prolonged hearings was consistent but Judge Desai was convinced that there was “no conspiracy behind the slaughter” and that the administration did all it could to control it.

“Jafri, by the judge’s reckoning, and that of Modi, was responsible for his own slaughter,” he laments.

Mander also argues in the book that recurring episodes of communal violence in Ahmedabad had altered the city’s demography, dividing it into Hindu and Muslim areas and Gulberg was among the last remaining “Muslim” settlements in the “Hindu” section of the city.

He says that Desai also disregarded the evidence in the conversations secretly taped by Tehelka reporters, mentioning that superior courts, according to Desai himself, have ruled that while a person cannot be convicted exclusively based on the evidence collected in such “sting operations”, such evidence is certainly “admissible as corroborative proof”.

“But he chose to disregard this evidence, not because there was proof that these video recordings were in any way doctored or false but simply because the Special Investigative Team (SIT) appointed by the Supreme Court of India chose to ignore this evidence,” says Mander.

According to Mander, the Tehelka recordings “certainly supported the theory that there was indeed a plan to collect, incite and arm the mob to undertake the gruesome slaughter”.

The SIT was headed by R.K. Raghavan, today Ambassador to Cyprus. Mander contends in the book that just because the investigators did not pursue Tehelka recordings in greater depth, Desai concluded that the “recordings cannot be relied upon as trustworthy of substantial evidence and establish any conspiracy herein”.

In the book, Mander takes stock of whether India has upheld the values it had set out to achieve and offers painful, unsparing insight into the contours of violence. The book is now available both online and in bookstores.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | News, Politics

New Delhi : On the intervening night of February 28 and March 1, 2002 when Gujarat was engulfed in flames, Lt. Gen Zameer Uddin Shah, met the then Chief Minister Narendra Modi, in the presence of the then Defence Minister George Fernandes, at 2 am in Ahmedabad and gave him a list of immediate requirements to enable the Army columns to fan out to restore law and order.

New Delhi : On the intervening night of February 28 and March 1, 2002 when Gujarat was engulfed in flames, Lt. Gen Zameer Uddin Shah, met the then Chief Minister Narendra Modi, in the presence of the then Defence Minister George Fernandes, at 2 am in Ahmedabad and gave him a list of immediate requirements to enable the Army columns to fan out to restore law and order.

But the 3,000 troops that had landed at the Ahmedabad airfield at 7 am on March 1, had to wait for a day before the Gujarat administration provided the transport — during which period hundreds of people were killed.

“These were crucial hours lost,” Shah, who retired as the Deputy Chief of Army Staff, has revealed in his upcoming memoir titled “The Sarkari Mussalman” (Konark Publishers) to be launched by former Vice President Hamid Ansari on October 13 at India International Centre here.

In the memoir, a copy of which is with IANS, Shah writes that the Gujarat government requested for deployment of the Army through the Union Home Ministry and the Ministry of Defence on February 28, 2002. The then Chief of Army Staff, General S. Padmanabhan was quoted by him as saying: “‘Zoom, get your formation to Gujarat tonight and quell the riots.’ I replied, ‘Sir, the road move will take us two days.’ He shot back, ‘The Air Force will take care of your move from Jodhpur. Get maximum troops to the airfield. Speed and resolute action are the need of the hour.'”

Upon arriving at the “dark and deserted” Ahmedabad airfield, he enquired: “Where are the vehicles and other logistic support we had been promised?” He learnt that the state government was still “making the necessary arrangements”.

“The crucial periods was the night of 28th February and the 1st of March. This is when the maximum damage was done. I met the chief minister at 2 am on the 1st morning. The troops sat on the airfield all through the 1st of March and we got the transport only on the 2nd of March. By then the mayhem had already been done,” Shah, who has been conferred Param Vishisht Seva Medal, Vishisht Seva Medal and Sena Medal for his services to the armed forces, told IANS.

Asked if the damage would be lesser had the army been allowed full freedom and provided with what he had personally asked Modi for, he agreed and said: “Most certainly the damage would have been much, much less had we got the vehicles at the right time. What the police couldn’t do in six days we did in 48 hours despite being six times smaller in size than them. We finished the operation in 48 hours on the 4th of March but it could have been finished on the 2nd of March itself had we not lost those crucial hours.”

He said that he is not blaming anyone in particular. “It may take some time in arranging transport but in a situation like that, it could have possibly been done faster,” he added.

He said the police were “dumb bystanders” while the “mob was setting fire on streets and houses”. They were taking “no action” to prevent the “mayhem” that was being done.

“I did see a lot of MLAs from the majority community sitting at the police stations. They had no business to be there. Whenever we used to tell the police to impose the curfew, they never did so in the minority areas. So the minorities were always surrounded by the mobs. It was a totally parochial and biased handling,” the decorated army veteran maintained.

Asked of the political links in the riot, Shah said that he does not “want to reopen any old wounds”, maintaining that the purpose of his memoir is “to tell the facts as they happened in Gujarat in 2002”.

“It takes three generations to forget. I do not want to reopen the wounds. I have spoken the truth about police and I stand by every word I have written,” he said.

The government had told the parliament in 2005 that 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus were killed, 223 more people reported missing and another 2,500 injured during the 2002 riots in Gujarat. Shah maintains in the book that the “official figures of deaths and damage do not reflect a true picture of the actual extent of the carnage”.

The book — packed with revelations as also his personal experiences in life, both as an army man and a Muslim in India — has been endorsed by at least two chiefs of army staff, including General S. Padmanabhan.

“Many eyebrows were raised when I nominate‘ ‘Zoom’ to lead the Army complement to Gujarat. Some seniors told me of their misgivings. I told them in no uncertain terms that the choice of troops and their leader was a military decision and not open to debate. The Army moved into Gujarat, led b‘ ‘Zoom’ whose ability, impartiality and pragmatic decision making, soon brought the situation under control,” Gen Padmanabhan wrote as an endorsement of the book.

(Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Books, News, Politics

By Saket Suman,

By Saket Suman,

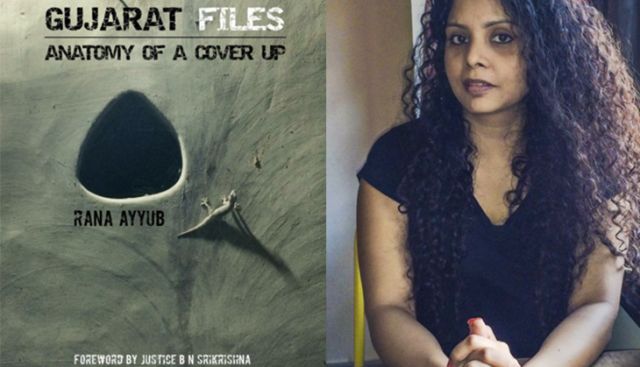

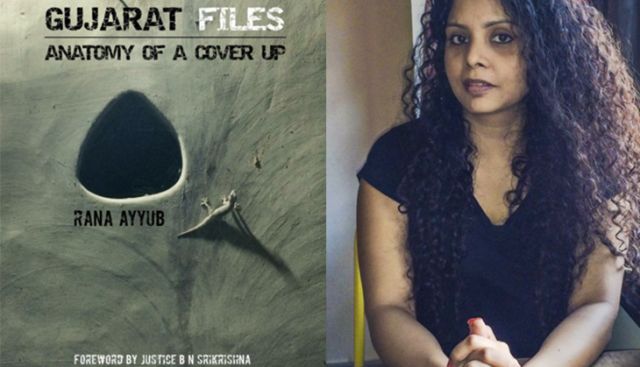

New Delhi : A biography that traces Baba Ramdev’s rise from godman to tycoon has been caught up in a legal storm for over 11 months; Amish Tripathi’s upcoming book has been served a legal notice and its launch postponed; a nonfiction account on Bastar by Nandini Sundar came under pressure from a state government; and a critical book on the 2002 Gujarat riots by Rana Ayyub could not find a publisher.

Those who disseminate ideas through books have had their share of political coercion. “As a publisher I find that I have faced pressure and censorship across all political regimes,” says Chiki Sarkar, publisher of Juggernaut Books.

But now, an insidious method of going against authors and publishers has emerged — of causing delays through the courts. The fear of legal suits and defamation charges has assumed such proportions that it has led to rejections and self-censorship among publishers, industry insiders say.

In a series of interviews with key people holding top portfolios in some of India’s most prominent publishing houses, IANS ran a reality check on whether or not they have faced issues like self-censorship or pressure from political groups or legal action during the four years of the Narendra Modi government.

“There has only been a few legal cases in the court, but we have not faced any political pressure,” says Kapish Mehra, Managing Director of Rupa Books.

What emerges from these discussions is that political pressures on publishing houses is not “a new phenomenon” — both parties, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Congress have practiced it. But the legal threat as a weapon to thwart public discourse through books has assumed menacing proportions.

Recently, writer Amish Tripathi was served a legal notice for his latest book “Suheldev & The Battle of Bahraich”. Tripathi announced the postponement of the July 16 launch “due to some circumstances beyond our control”. Earlier, pre-orders were being booked.

The announcement of the book was made at Sonali Bendre’s Book Club in Mumbai and the cover was launched by actor Varun Dhawan, who too has been sent a legal notice.

The book is said to revolve around Raja Suheldev, a semi-legendary Indian king from Shravasti in Uttar Pradesh. In the legal notice sent on June 25, a copy of which IANS has, the sender has accused the author and bollywood actor Varun Dhawan, of hurting “his and his communities’ sentiments”.

“Raja Suheldev is a godly figure among the Rajbhar community. I have received several messages and complaints from members of our community that Amish Tripathi has hurt their sentiments,” Jaiprakash Rajbhar, who sent the notice, told IANS over phone from Mumbai.

Rajbhar, an advocate, said that Uttar Pradesh text books for Class VI clearly point out that Suheldev was from the Rajbhar community. “The author has referred to him as somebody from “other caste”. This is a historical blunder,” he said.

“Moreover, the cover of the book shows Suheldev half naked. A king who is fighting a battle and riding a horse could not afford a piece of cloth to cover his body?” he asked.

On such grounds are objections to work of great artistes being raised. Tripathi and publisher Westland have declined comment on the issue.

Tripathi is a writer of fame and repute. With gross retail sales of Rs 120 crores, his novels include “The Immortals of Meluha”, “The Secret of the Nagas”, “The Oath of the Vayuputras”, “Ram: Scion of Ikshvaku” and “Sita: Warrior of Mithila”.

Sarkar, who started her publishing career at Bloomsbury in London, then worked at Penguin Books India and rose to become India publishing head after Penguin’s merger with Random House, said that Juggernaut has published many politically brave books — “I am a Troll”, “Shadow Armies”,”The Burning Forest” and “Mothering a Muslim”.

“But the book we have run into the biggest legal trouble over — the biography of Baba Ramdev — is a non-political book,” Sarkar told IANS.

The publication and sale of “Godman to Tycoon: The Untold Story of Baba Ramdev”, authored by Priyanka Pathak-Narain, has been stayed by the Delhi High Court, after a lower court had lifted a similar order earlier.

According to Baba Ramdev’s petition, the book mentions some details from his past that are “irresponsible, false (and) malicious”. Certain content, Ramdev’s petition said, “had been added without evidence and verification”.

Juggernaut said in its appeal that the book was “truthful, even-handed and balanced consideration of the history of Baba Ramdev, which has been meticulously researched and is based on public and recorded sources, most of which have been in the public domain for years”.

It all began on August 4, 2017 when in an ex-parte order, the Additional Civil Judge at the District Courts of Karkardooma in Delhi asked Juggernaut not to publish or sell the book. The injunction was lifted nine months later in April 2018.

But the freedom was not to last too long. In May 2018, the Delhi High Court restored the temporary injunction. Ramdev’s lawyer had told the court that certain parts of the book were “unfounded and had misleading material which are malicious and scandalous”.

Pathak-Narain, the author had told the court that the contents of the book represented “only reported true facts as gleaned from publicly available documents and contains legitimate and reasonable surmises and conclusions drawn therefrom”.

The next hearing in the case is in August. “We will fight it out up till the Supreme Court, if need be,” says Sarkar.

“The Burning Forest: India’s War in Bastar” by Nandini Sundar, professor of sociology at Delhi University, who has been writing about Bastar and its people for 26 years, faced covert pressure from the state government to not publish or distribute the book. She chronicled how the armed conflict between the government and the Maoists had devastated the lives of some of India’s poorest, most vulnerable citizens in Bastar.

Fear of legal cases or political pressure often lead to publishers exercising their own version of self-censorship. Journalist Rana Ayyub, who was lately in the news for facing hate and threat messages on social media, could not find a mainstream publisher for her book “Gujarat Files”, an undercover expose of the 2002 riots in the state that claimed the lives of over 1,000 Muslims. She ended up publishing it herself. Ayyub, in a text message from London, expressed her unavailability to respond at present.

Industry insiders say that “legal suits, defamations proceedings and temporary injunctions” were their greatest fear. Injunctions can kill the fate of any book. They say that in eight out of ten cases, where a book can potentially be stayed by a court, mainstream publishers would avoid publishing it — or at least tell the author to remove content or “tone down” portions which are “objectionable”.

(This is first article in the two-part series on freedom in book publishing. Saket Suman can be contacted at saket.s@ians.in)

—IANS

by admin | May 25, 2021 | News, Politics

Zakia Jafri

Ahmedabad : The Gujarat High Court on Thursday rejected the plea of Zakia Jafri, the wife of slain former MP Ehsan Jafri, challenging a clean chit by the Special Investigation Team to then Chief Minister Narendra Modi and other top officials in the 2002 Gujarat riots.

The court rejected Zakia Jafri’s plea on allegations of “a larger conspiracy” behind the riots.

Ehsan Jafri, a Congress leader, was one of the 69 people killed when a large mob attacked Gulbarg Society in Ahmedabad on February 28, 2002.

—IANS