Title: Pakistan – Courting the Abyss; Author: Tilak Devasher; Publisher: Harper Collins India; Pages: 472; Price: Rs 599

What will be Pakistan’s fate? Acts of commission or omission by itself, in/by neighbours, and superpowers far and near have led the nuclear-armed country at a strategic Asian crossroads to emerge as a serious regional and global concern while creating many grave internal faultlines that raise doubts about its viable existence – or even existence for that matter.

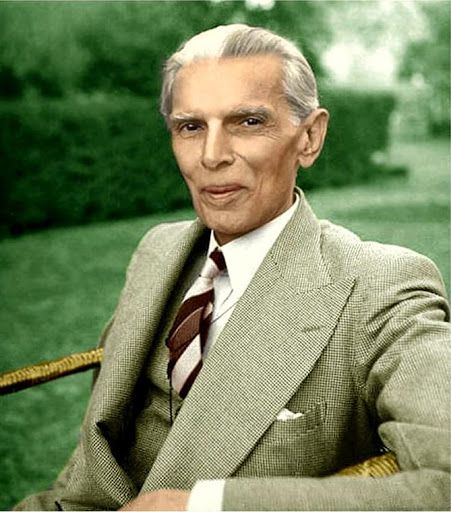

Could Mohammad Ali Jinnah, as he left New Delhi for ever on August 7, 1947 have visualised the “moth-eaten” country he obtained in less than a decade with his iron determination, the machinations of the imperial power and mistakes of his opponents, “would within twenty-four years be broken into two?”

Or that the “rump come to be variously described as ‘deeply troubled’, ‘in terminal decline’, ‘in crisis’, ‘failing’, ‘on the edge’, ‘on the brink'”, unable to “provide minimum safety and law and order to its citizens” or “survive without repeated external financial support”, become “a hotbed of terrorism, both internal and external” or “a nuclear proliferator?” asks Pakistan expert Tilak Devasher.

Devasher, who retired in 2014 as Special Secretary in the Cabinet Secretariat where he specialised in security issues in India’s neighborhood (and continued to maintain the interest), goes on, here, to undertake a full-scale and clinical examination of the various ills plaguing the country.

His research and analysis indicates that the roots of many of Pakistan’s problems lie in its past, in some cases, stretching back to before its founding. Also at fault, he finds, is the nature of the party that accomplished the work, the tactics used by the founding father, probably without much thought to their future implications (rather atypical of the forensically precise Jinnah), other structural weaknesses that were ignored, besides the latter errors.

Devasher admits his “fascination” with Pakistan doesn’t stem from being of a Partition-affected family or even Punjabi, but from the stories told by his air force officer father, about two of his superiors who later on headed the Pakistan Air Force. His interest was further strengthened by his own reading of Indian history, especially the freedom struggle, but this also raised questions about the two countries’ different courses.

As a history student, he was not content to “skim the surface” and went deeper to know more about how Pakistan’s creation impacted its future, and the “real issues that plagued the country and its people”, beyond the “exciting issues” figuring in the headlines.

This, Devasher seeks to bring out in this “holistic book” which encompasses both “exciting issues” like terrorism and the roller-coaster course of relations with India as well as “boring”, but no less vital, ones like ideology, economy, environment, demographics and other internal dynamics. He however stresses it is not a comparative study with India.

Beginning, most methodically, from the foundations, comprising the movement for Pakistan and legacy, he goes on to the building blocks, or the Pakistani ‘ideology’ and provincial relations, the framework, comprising the army and its relations with the state and society, and the superstructure which covers Islamisation and the sectarianism that also ensued, the role of the madarsas and then terrorism.

Then, he outlines the worrying state of the crucial “WEEP” sector – water, education, economy and population, and takes up relations with four key states – India, Afghanistan, China and the US.

Devasher, who ends almost every alternate chapter with how the discussed issue is leading Pakistan to the abyss, is quite gloomy in his conclusions, mostly arrived at careful and reasoned analysis, quite free from prejudice.

The main, he singles out, are the weakness of Islam as a uniting force (as the Munir Commission found in the 1950s), of hate (and why) and quest for parity with India, and the weakness of the political culture (due to the spells of military rule), which in turn affects society, economy and security.

Though he gives no dramatic prescriptions or ways to deal with the eventuality of an implosion, which he gives a decade or so, what makes this book essential reading is its warning against emulating any of Pakistan’s failed, fatal choices – especially the role of religion and hate of the’other’ for nation-building – which some of its more stable neighbours could well pay heed to.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in )

0 Comments