By : Abdul Shaban

Professor,Tata Institute of Social Sciences,Deonar, Mumbai

Muslims constitute the largest religious minority group in many states, including Maharashtra. The Muslim population in the state was about 10.27 million in 2001 (Census of India, 2001), which constituted around 10.6 per cent of the total population of the state. Among the states/UTs, Maharashtra stands at the 12th position in terms of the share of Muslim population to the total state population. In terms of absolute number, Maharashtra has the fourth highest number of Muslims after Uttar-Pradesh, West-Bengal and Bihar. More than 70% of the Muslim population in the state lives in urban areas. A large proportion of this urban population is located in Mumbai, Mumbai (Suburban) and Thane districts. The other cities like Nagpur, Pune, Nashik and Aurangabad also have a significant number of Muslims. A large spatial variation is seen in the distribution of Muslim population in Maharashtra. While some districts like Mumbai (22 per cent), Aurangabad (19.7 per cent), Akola (18.2 per cent), Mumbai Suburban (17.2 per cent), and Parbhani (16 per cent) have a very high concentration of Muslims; some tribal districts in Vidharba region like Gondia, Gadchiroli, and Bhandara have very less share of Muslim population to their respective total population. In this paper, I attempt to examine the employment and poverty among Muslims in Maharashtra using Census of India (2001) data and the sample survey conducted by me in 2009.

Occupation and work participation rate

There are significant religion-wise variations in occupation in the state. First, the share of cultivators in total workers of the Muslims is significantly lower than that for Hindus. This is mainly because of the fact that ownership of agricultural land among Muslims is significantly lower than that among Hindus. Only 8.1% of total Muslim workers are cultivators as compared to 32.2 per cent of Hindus. In rural areas, the share of Muslim cultivators rises to 21.8% but it still remains significantly lower than that of Hindus (45%). Second, the share of agricultural labour in rural areas among Muslims is substantially higher than that among Hindus. In rural areas of the state, 44.4% of Muslim workers are engaged as agricultural labour in comparison to 36.1% among the Hindus. The share of female agricultural labourers among Muslims is significantly higher in comparison to Hindus: 61.6% of Muslim female workers are engaged as agriculture labour in comparison to 45.5 among Hindus. Third, the share of Muslim workers engaged in household industries both in rural and urban areas is higher than those for Hindus. Out of the total workers in respective religious communities, 3.6 per cent of Muslims and 2.6 per cent of Hindus are engaged in household industries. Further, the share of females in household industries among Muslims is significantly higher than their counterparts among Hindus and males within the Muslim community. This again shows that lots of creativity exists among Muslim women and that needs to be channelized for worthy economic returns.

Fourth, the lack of land holdings, precarious nature of employment opportunities in rural areas, and in recent years rising communal sentiments even in rural areas, push Muslims to urban areas for their livelihood and to settle down in the already existing Muslim concentrated areas. The employment implications for this are dire to the community and individuals. Given that there is a lack of large formal or informal businesses in Muslim concentrated areas, they have either to work as low paid informal workers within the ghettos or search for some self-employment opportunities. Further, given that a large share of the Muslims migrating to urban centres come from artisan class like tailor, carpenter, embroider, etc. they try to search for these opportunities in urban centres and also many of them work in garage or open their garage after acquiring related skills. A sizeable share of workers also gets engaged in hawking or becomes available as driver who can be hired on daily basis, as in Mumbai. The implication of this informalisation of the community workers is huge. It has impact on their income (lower income), health (due to more hour of work in often unhealthy environment), self-prestige, and contribution to the wider society. Although, detailed categorised data is not provided by the Census of India, in Maharashtra 70.7% the total Muslim workers are engaged in service and industrial sector mainly as informal workers as compared to 38.7 per cent of Hindu workers. Artisan industry has been dominated by males in India. Further, given the anonymity of city life and unknown faces, the trust which often motivates women to work or go to a place of work cannot be channelized in urban areas. Therefore, we find a substantially lower proportion of females among Muslims in informal sector than their male counterparts. However, their share remains considerably higher than that for their female counterparts among Hindus.

Another area of concern for Muslims in Maharashtra (also in other states) has been their lower work participation rate, specifically of women. From the discussion above, it becomes clear that lower work participation rate of women among Muslims is mainly a manifestation of the type of work Muslims are engaged in. As mentioned above, most of the artisan activities have traditionally been male dominated and the areas where Muslim women can play important role like in embroidery, tailoring, etc, need capital, space, market which women located in the ghettoes are hardly able to secure. Added to this is pardah system which hardly allows women to venture out and seek some recourse to the above problems. The statistics at the state level reveals that in comparison to work participation rate of 50.0 per cent for Muslim males, the work participation rate for Muslim female is only 12.7 per cent. This means that on an average only about 13 females out of 100 are working. In comparison to Muslim females, the work participation rate for Hindu females is 32.2 per cent.

Economic Activity status of Muslims in Maharashtra

A detailed survey of Muslim household in Maharashtra was conducted by TISS in May-October 2009 to understand the socio-economic conditions in which Muslims live. The survey revealed that of the total population, 31% (31.7% male and 30.3% female) attends educational institutions. About 18.8% of the population attends domestic duties. This means they are also not engaged in any type of gainful economic activities or works. This 18.8 per cent of population is mainly comprised of females. The next 11.3% of population again fall into non-workers category or ‘others’ category, mainly comprising children. The survey shows that higher share of workers among Muslims is engaged in self-employment (11.4% of population). Fourth, there is a huge casualisation of labour among Muslims: 12.2 per cent of the population is engaged as casual worker in public or other types of works. In fact, the participation in public work as casual worker is considerably lower than in other types of work. This shows that public works are not reaching to Muslims or they are not able to effectively participate in government initiated wage employment or other programmes. Only about 10 per cent of the population is having regular employment, while 5.5 per cent of the population is unemployed.

Table 1: Distribution of total population (all age groups) by current activity status

| Activity status | Persons |

Percentage |

||||

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | |

|

||||||

| i. Own account workers | 1376 | 215 | 1591 | 11.9 | 1.9 | 7.0 |

| ii. Employers | 94 | 14 | 108 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| iii. Working as helper in household enterprise | 83 | 17 | 100 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

|

||||||

| Working as regular salaried/wage employees | 2011 | 332 | 2343 | 17.4 | 3.0 | 10.4 |

|

||||||

| 324 | 92 | 416 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 1.8 | |

|

1470 | 436 | 1906 | 12.7 | 3.9 | 8.4 |

|

||||||

| 246 | 139 | 385 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.7 | |

|

125 | 287 | 412 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 1.8 |

|

5 | 0 | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

3 | 1 | 4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

||||||

| 430 | 378 | 808 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.6 | |

|

290 | 76 | 366 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 1.6 |

|

||||||

| 3657 | 3348 | 7005 | 31.7 | 30.3 | 31.0 | |

|

75 | 4165 | 4240 | 0.6 | 37.7 | 18.8 |

|

10 | 214 | 224 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 1.0 |

|

26 | 6 | 32 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

|

48 | 26 | 74 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

|

5 | 12 | 17 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

|

1266 | 1281 | 2547 | 11.0 | 11.6 | 11.3 |

| Total | 11544 | 11039 | 22583 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Source: TISS Sample survey, May-October 2009.

Unemployment rate among Muslims

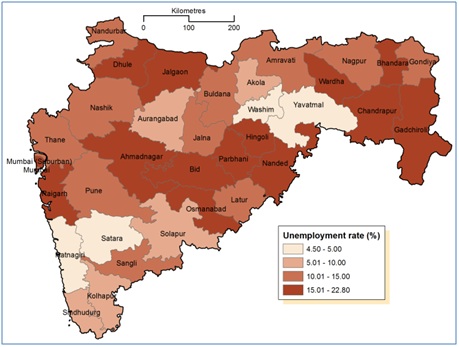

TISS survey shows that there is a higher unemployment rate among Muslims in districts of central and northern Maharashtra, and south-eastern Vidarbha (see Figure 1). In many of the districts, namely, Ahmadanagar, Bid, Parbhani, Hingoli, Nanded, Osmanabad, Dhule, Wardha, Chandrapur, Gadchiroli, Raigad and Mumbai, the unemployment rate among Muslims is as high as 15 -20 per cent. Only in districts of south Western Maharashtra and Konkan, where there is higher share of cultivators, the unemployment is lower. The urban unemployment rate is significantly higher (more than 20%) in districts of Raigad, Bid, and Chandrapur, while in rural areas it is above 20 per cent in districts of Wardha and Bhandara.

Among Muslims, the female unemployment rate is found significantly higher than the unemployment rate among males. This shows that Muslims women want to work but due to odd types of job (in which their male counterparts are often engaged), insecurity in treading the areas beyond usual places of Muslim concentration, lack of relevant knowledge and skills and lack of space and capital, make unemployment higher among Muslim females. The ghettoization of Muslim population in urban centres adds to this problem.

Table 2: Unemployment Rate (%) among Muslims by districts, sector and gender

| Districts | Total | Urban | Rural | Male | Female |

| Nandurbar | 12.0 | 10.7 | 13.3 | 9.1 | 21.6 |

| Dhule | 16.5 | 19.4 | 7.5 | 12.1 | 25.3 |

| Jalgaon | 15.2 | 16.3 | 13.4 | 11.9 | 28.8 |

| Buldhana | 13.1 | 6.5 | 16.4 | 14.8 | 8.3 |

| Akola | 8.9 | 12.5 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 24.4 |

| Washim | 4.5 | 2.3 | 7.5 | 1.7 | 14.3 |

| Amravati | 14.8 | 11.8 | 18.4 | 7.9 | 35.7 |

| Wardha | 19.7 | 18.5 | 21.4 | 12.0 | 40.5 |

| Nagpur | 10.5 | 9.3 | 13.0 | 8.7 | 14.1 |

| Bhandara | 22.8 | 16.1 | 29.5 | 18.7 | 34.4 |

| Gondiya | 13.0 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 12.5 |

| Gadchiroli | 18.1 | 21.4 | 14.0 | 12.6 | 34.4 |

| Chandrapur | 15.7 | 18.3 | 13.0 | 7.4 | 33.3 |

| Yavatmal | 4.5 | 6.4 | 2.6 | 5.6 | 2.2 |

| Nanded | 15.7 | 18.8 | 12.4 | 14.0 | 23.1 |

| Hingoli | 16.7 | 13.6 | 20.0 | 16.2 | 20.0 |

| Parbhani | 16.0 | 17.2 | 14.3 | 10.8 | 31.0 |

| Jalna | 10.4 | 12.7 | 8.3 | 7.0 | 18.4 |

| Aurangabad | 8.8 | 11.4 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 19.2 |

| Nashik | 11.1 | 11.7 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 19.8 |

| Thane | 12.6 | 12.7 | 12.0 | 10.8 | 24.7 |

| Mumbai (Suburban) | 15.2 | 15.2 | — | 11.8 | 30.5 |

| Mumbai | 13.7 | 13.7 | — | 12.4 | 20.2 |

| Raigarh | 15.6 | 23.4 | 6.9 | 12.9 | 28.6 |

| Pune | 11.2 | 10.0 | 15.4 | 7.6 | 18.7 |

| Ahmadnagar | 15.5 | 11.3 | 18.6 | 12.4 | 25.7 |

| Bid | 18.4 | 24.1 | 14.6 | 15.0 | 27.5 |

| Latur | 11.3 | 5.7 | 14.3 | 6.1 | 27.0 |

| Osmanabad | 15.1 | 14.6 | 15.4 | 12.2 | 25.0 |

| Solapur | 7.1 | 8.9 | 3.8 | 6.9 | 8.0 |

| Satara | 4.5 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 9.1 |

| Ratnagiri | 4.8 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 2.2 | 12.1 |

| Sindhudurg | 8.6 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 4.8 | 26.1 |

| Kolhapur | 6.6 | 5.7 | 7.8 | 3.2 | 14.0 |

| Sangli | 10.1 | 8.5 | 11.4 | 5.8 | 26.9 |

| Maharashtra | 12.7 | 13.1 | 11.8 | 9.9 | 22.2 |

Note: self-employment rate = (total persons self-employed/total persons in labour force) *100

Source: TISS Sample survey conducted during May-November 2009

Age and activity status

Given the informal nature of economic activities in which most of the Muslim workers are engaged in, they initially work with some employers and later start their own activities and become own account workers. The initial work with employer in the informal sector provides the needed knowledge and experience to deal with day-to-day complexities in running of their own small businesses. About one-fifth of the workers in the age-group 20-30 years work as salary/wage employee. At this age, the share of own account workers is less than 10 per cent. Thereafter, the share of own account workers rises more than 15 per cent in the decennial age-group till 60 years of the age. Another noteworthy point which emerges from the data is that women with their age move from domestic work to some other type of work. The share of domestic workers declines significantly beyond the age of 40 years. This shows that when women become mother or take up the responsibility of the household, they also start working.

Muslims’ share in government jobs

The share of Muslims in government employment is quite low. Muslims constitutes 10.6 per cent of the total population in the state of Maharashtra but their share in state government services is only 4.4 per cent. The reasons for this significantly lower share in state government services are many: they range from poverty, lack of education and social infrastructure in Muslim concentrated areas, segmentation of the society on caste and religious lines which constrain access to jobs by Muslims, and lack of effective enabling programmes by the government to mainstream the Muslim community. Further, frequent occurrence of communal riots breaks the back-bone of the community economically and psychologically. Muslims, in turn, then start avoiding mainstream section of society and start playing on the tune of conservative elements within the community. This further pushes back the community from educational and employment fronts. The situation in Central Government jobs is also not different from that at the state level. The intake of Muslims in Indian Administrative Services (IAS) has been very limited over the years (about 3%), and the gravity of the situation can be imagined as at present there is no Muslim IAS officer in Maharashtra State Cadre.

Employability

The Employability refers to likelihood of an individual getting a suitable job given his/her skill and educational level. The new economy which has emerged after the liberalization in 1991-92 requires altogether different sets of skills and attitude. In earlier days when the government jobs were the main source of employment, educational level was the main criterion for jobs. But now emerging private sector and transforming and de-bureaucratising government sectors desire new skills and attitude for jobs and the educational level remains only one of the criteria. In general, the major determining factors of employability are (1) educational level, (2) soft-skills, like communication skill, multi-tasking attitudes and capacity, (3) social networking, and (4) the attitude and orientations of decision makers/employers. It is found that in all the four criteria, Muslims are not able to do very well. The educational level of the community is very much low (see chapter 3). Another major constraint which Muslims face in getting job is the lack of knowledge of English language. Given that most of them are not educated from good institutions/schools and the medium of their education largely remains Urdu, Hindi or Marathi, they find it difficult to have fluency in English even when they learn English language later on. This constrains the employability of the workers/youth.

There is a significant disconnect of the Muslims population with the ruling elites in the country. It is well known that many of the recruitments and employments both in private and public sectors are garnered by social networking than any other objective criteria. The image which the media and politician have created of the Muslim community also comes in the way of effective networking with the other religious groups. The Muslims are largely seen with suspicion and this suspicion undermines their effective relationship with ruling class and thus job opportunities/possibilities. Further, the traditional leadership within the community which is largely based on emotional rhetoric/backward looking mindset has also been responsible for this state of affairs. In fact, the leaders have been unable to connect the Muslim masses with the ruling class, but they have created a situation in which the Muslim community has largely been used as vote bank. No doubt, the change in attitude of leaders within the community is very much required for the development of the Muslim community.

The religious biases in selection process are open secret in the country, although many those at the helm of affairs and so called intellectuals shy away from accepting this. There is a class interest which prevents accepting the fact that there is discrimination against Muslims in job market. The situation requires that ‘ostrich mentality’ is abandoned by those who are at the helm of affairs and are opinion makers. There is a need to encourage inclusion of the Muslim community in the formal job market, including government services, and this requires no less than the approach which has been adopted for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. In case of Muslims, religious bias must be acknowledged as the major sources of problem in their deprivation. The effective development of the country will never be possible by leaving behind 14 per cent of the population deprived.

Land ownership and poverty

It will not be hyperbole to say that today Indian Muslims are among the poorest of the poor. The Muslims in the country have been left behind on socio-economic development ladder since the Independence. The marginalization of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes over centuries in India had resulted in their profound deprivation. After the Independence, affirmative actions through policy, programme and importantly reservation in government services and mandatory representation of the communities in decision making processes and recruitments have enabled them to move fast on the ladder of socio-economic development. However, at the same time, the country has seen emergence and making of new dalits of the country, the Muslims.

Ownership of land: There is a higher level of landlessness among the Muslims in the state. Only about 10 per cent of the Muslim community owns any land. Further, given the economic non-viability of marginal holdings and lack of fruitful employment in rural areas, Muslims in large number over the years have migrated to urban areas leaving behind their land in villages. This is one of the reasons why many Muslim families living in urban centres claim that they own land. About 7 per cent of the Muslim families in urban area claim that they own agricultural land and most of the owned land is below 2.5 acre or one hectare. As expected, larger share of families in rural areas in comparison to those in urban centres own land. However, again most of the owners of land fall under marginal farmer category. About 17 per cent of the families own land in rural areas, but about 10.8 per cent belong to marginal farmer category, 4.6 per cent to small farmers category, 1.2 per cent semi-medium farmer category and the rest 0.2 per cent to medium farmer category.

Table 3: Ownership of land by families (%)

| Sector |

Farmer type |

Total |

||||

|

Landless |

Marginal Farmer (< 2.5 acre) |

Small Farmer (2.5 – 5.0 acre) |

Semi-medium Farmer (5.0 – 10.0 acre) |

Medium Farmer (10.0 – 25.0 acre) |

||

| UrbanRural |

93.2 |

6.3 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

100.0 |

|

|

83.2 |

10.8 |

4.6 |

1.2 |

0.2 |

100.0 |

|

| Total |

89.9 |

7.8 |

1.7 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

100.0 |

Source: TISS sample survey, May-Nov 2009.

Distribution of income

The per capita monthly income for Muslims in the state was Rs.746 in 2009. The per capita monthly income in urban areas (Rs.816) was almost 36 per cent higher than the per capita income in rural areas (Rs.599). It is interesting to note that the per capita monthly income for Muslim OBC (Rs. 742) in the state is marginally higher than the per capita income for non-OBC Muslims (Rs.743). The districts where OBC per capita income is higher than non-OBC Muslims are Dhule, Bhandara, Nanded, Parbhani, Jalna, Aurangabad, Nashik, Mumbai, Bid, Latur, Osmanabad, and Kolhapur.

Muslims have been among the economically most deprived communities in the country. NSSO data (as quoted in Sachar Committee Report, 2006) shows that at all-India level, urban poverty among Muslims stood at 38.4 per cent, while it was 36.4 per cent among schedules castes and scheduled tribes in 2004-05. In Maharashtra the gap between scheduled castes and scheduled tribes’ urban poverty rate and that among Muslims was even higher: 33 per cent for schedules and scheduled tribes, and 49 per cent for Muslims. Further, as per the NSSO data, about one-half of the Muslim population in urban areas in Maharashtra was living below poverty line in 2004- 2005. However, the sample survey conducted by TISS shows that urban poverty among Muslims in the state stood at 59.4 per cent, about 10 per cent higher than that shown by the NSSO data in 2004-05.

Table 4: Head count ratio and household poverty among Muslims in Maharashtra

| Sector |

Head count ratio (%) |

Family (%) |

||||

| OBC |

General |

Total |

OBC |

General |

Total |

|

| Total | 60.20 |

59.20 |

59.50 |

55.2 |

55.4 |

55.4 |

| Urban | 59.00 |

59.60 |

59.40 |

59.2 |

56.2 |

57.3 |

| Rural | 62.60 |

58.20 |

59.80 |

56.6 |

55.7 |

56.0 |

Note: The poverty line income for urban and rural areas is considered to be Rs.700 and 500 respectively. This income is based on the final set of new state-wise poverty lines by Expert Group under Suresh D.Tendulkar (Planning Commission 2009).

Source: Source: Based on TISS sample survey, May-Nov 2009.

Ownership of ration card

The ration card is an important household asset and particularly for those living below poverty line. It assures access to various government programmes and also acts as proof of local citizenship. TISS sample survey reveals that in Maharashtra only 78.8 per cent of the total Muslim households have ration card. In rural areas (81%) the ownership of ration card is higher than that in urban areas (78%). This shows that about one-fifth of the Muslim households in the state do not own ration card. The most surprising aspect is that though about 60% of Muslim population in the state lives below poverty line, only 14% of Muslim families in the state (11.6% in urban areas, and 19.5% in rural areas) have BPL card. This is one of the major reasons of the exclusion of Muslims from government programmes and a sustained poverty among them.

0 Comments