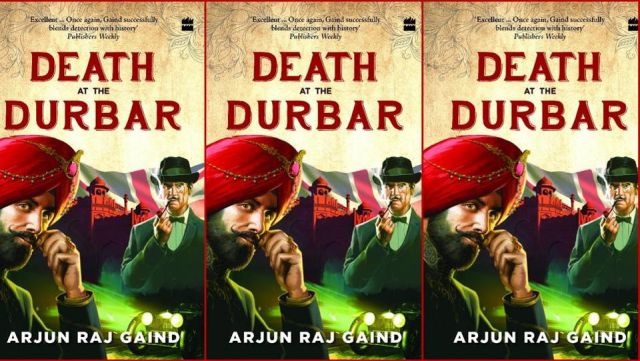

Title: Death at the Durbar; Author: Arjun Raj Gaind; Publisher: HarperCollins India; Pages: 368; Price: Rs 399

It is India in 1911 — the Raj’s high-point, with the King Emperor setting foot in his prized dominion for the first time. The colonial administration is sparing no efforts to mount a grand Coronation Durbar where India’s princes will pay him homage. But a dead “nautch” girl hanging in the royal residence was certainly not part of the arrangements.

With the British monarch arriving the day after the next, the authorities have limited time to solve the crime, and more importantly, ascertain if it portends any threat to his life. Involving police seems the obvious step, but in light of the simmering discontent and fear of the incident leaking and casting a scandalous shadow over the grand event, they take a gamble.

On advice of royal ADC Malik Umar Hayat Khan, the Viceroy, Lord Hardinge, summons Sikander Singh, the Maharajah of Rajpore (in the Punjab) and an amateur detective, to solve the mystery — within 24 hours.

Though our hero is put out by the peremptory way he had been called and how some officials — especially the upcoming Michael O’Dwyer — are not enthused by his involvement (though Punjab Lt Governor Sir Louis William Dane is supportive), he is not one to skip such a challenge.

The stage is thus set for the stirring second installment of “The Maharaja Mysteries” by Arjun Raj Gaind, who moved from graphic novels to the equally promising, though thoroughly underutilised, area of Princely India and its crimes.

And in His Highness Farzand-e-Khas-i-Daulat-i-Inglishia, Mansur-e-Zaman…or, simply, Sikander, he has a worthy protagonist, with a keen intellect and interests beyond wealth, women and wine.

“Gold he was content to leave to the Nizam of Hyderabad, wine to the Gaekwad boys, polo ponies to his cousin Bhupinder of Patiala, and fast women to his dearest friend, Jagatjit of Kapurthala”, but mysteries are something Sikander cannot resist.

But after identifying the victim as a dancing girl, the circumstances of the murder and some traits of the probable murderer, he will not have an easy time of it.

For he learns the girl was brought to the camp as a “gift” for the King by the Maharaja of Kapurthala, and her last visitors included the Nizam, the Maharajas of Patiala, Alwar and Gwalior, the dowager Maharani of Bharatpur, a British journalist, and, “unofficially”, a messenger from the Maharaja of Kashmir, an Indian who said he was her uncle, as well as two British ladies.

While the prospect of questioning all these potentates — who outrank him in honour and protocol many times over — and others is daunting, Sikander also has to handle British officer Capt Arthur Campbell, attached to him to “aid” him, investigate a group of high British officials’ wayward sons, and negotiate among the conflicting advice he gets from two peers (the Maharajas of Bikaner and Baroda).

But even with the time constraints, will our princely detective be allowed to operate freely to find the culprit, or will other considerations, chiefly political, prevail?

Find out in Gaind’s masterful evocation of a glorious, bygone era with a host of larger-than-life characters, especially the Maharajas, who span both saints and scoundrels, demonstrate both parsimony and profligacy, and are fervent British loyalists or principled Indian nationalists.

Though the engrossing mystery has a rather tame denouement and a mistake or typo or two (Nadir Shah invaded India in 1730, not 1540), the real value is in the atmosphere — of a different Delhi in both time and space — and characterisation, especially of the princes with their idiosyncrasies or darker sides.

There is the Nizam, who, offered a cigarette, insists on taking the case too, intelligent minds like Ganga Singh of Bikaner or Sayaji Rao Gaekwad of Baroda, twisted, violent minds like Jey Singh of Alwar and Tukoji Holkar of Indore, Kashmir’s scheming regent, the redoubtable Maharani of Bharatpur, who, Gaind regrets, history has neglected, the lovelorn Jagatjit or Jitendra Narayan of Cooch Behar and many more.

Complementing them are a range of British officials with a equally wide gamut of perspectives towards India and Indians — sympathy, tolerance, indifference and repugnance.

In all, it makes for a heady cocktail — and there are many points left hanging for the next installment, which we hope will come soonest.

(Vikas Datta can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in )

—IANS

0 Comments