Will Islamic finance solve the growth problem for “all mankind”?

By Dr Piotr Konwicki

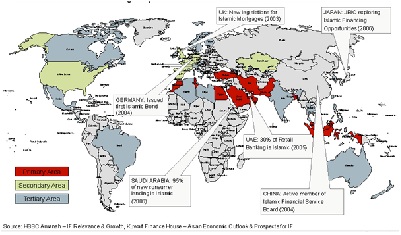

Turkey’s G20 Presidency has made financing for growth a key component of its agenda and will promote Islamic finance as a tool to facilitate this worldwide. At a recent IMF discussion the Turkish deputy prime minister told the audience that Islamic finance “is for all mankind” and praised that fact that the UK as one of the leading Islamic finance centres, is the first country outside the Muslim world to issue Islamic bond (Sukuk)

Turkey stresses that since the global financial crisis, traditional sources of infrastructure and SME finance have been constrained. The banking sector, which has traditionally been a major source of funding, has undergone a significant deleveraging process. Against this backdrop, there has been a gradual shift towards a model that includes a greater share of asset-based funding, pooling in private sector resources and designing appropriate risk sharing methods.

Islamic finance – the fastest growing area of finance in 21st Century, with assets ascending from $600 billion in 2007 to over $1.3 trillion in 2012 – seems to “tick” many of these boxes.

Islamic finance is a type of financial system that operates according to Sharia – a legislative framework, based mostly on Quran, which regulates all aspects of Islamic life. The two foundational principles are the prohibition of interest (riba) and Profit and Loss sharing. No Islamic finance product can involve Rishwah (corruption), Maysir (gambling), Gharar (unnecessary risk) and Jahl (ignorance).

Proponents of Islamic finance stress that in particular the risk-sharing principle re-creates a link between lenders and firms, making banks behave more like partners in business. An Islamic bank has a duty to help its customer and, if necessary, share some of the project losses. During the financial crisis trust has been severely tested and in particular SMEs often perceive banks as a source of the problem, not a solution, so this is effectively a more “ethical” model.

Contracts form the backbone of the profit-and-loss-sharing model of Islamic financing. For example Mudarabah is basic contract made between an investor who solely provides the capital and an entrepreneur who solely manages the project. If the venture is profitable, the profit will be distributed based on a pre-agreed ratio.

Proponents of this model link it to the Prophet Muhammad’s communitarian vision that Muslims with wealth should invest it productively to expand the welfare of the community, rather than simply being moneylenders who extract rents regardless of success or failure.

Islam makes it clear that this extension of the community welfare applies to all people, not only Muslims. This has been noted, among others by the Osservatore Romano, which in 2009 wrote that conventional banks should look at the rules of Islamic finance to restore confidence amongst their clients at a time of global economic crisis.

Islamic finance also has a unique potential correctly picked-up by Turkey. A recent Pakistani survey shows that (1) about 70% of the population is excluded for the banking system due to the low income levels and (2) when a first-time customer enters the market, there is an 86% chance that he will choose an Islamic bank.

Peruvian economist H. DeSoto coined a term of “dead capital” – physical resources and capital that are not used for any purpose other than to provide physical service to their owners. He estimates that the developing and former communist countries possess US$9.3 trillion worth of this and suggests that the ability of using this capital as a productive asset is what distinguishes the rich from the poor. Islamic finance carries a potential – through its risk-sharing and possibility of microloans – to put this capital into action and lift many people from poverty; one of the United Nations Millennium Development goals.

However despite its significant growth and ethical appeal, Islamic finance faces an array of challenges and needs to develop products which meet the sophisticated needs of its customers if it is to reach all Muslims, let alone ‘all mankind.’

Islamic Finance is generally more expensive than conventional banking due to high transaction and monitoring costs. Each Islamic financial institution employs a Sharia committee to oversee transactions and confirm compliance with Islamic Law. The existence of such a committee increases the cost base – while it is difficult to precisely assess it, for example Malaysian Takaful (Islamic insurance) companies in 2010 had 50% higher management cost ratio compared with traditional insurance firms.

Islamic finance also remains inferior to conventional banking and finance in terms of product development. It copies the financial instruments from the conventional sector and often fills the gaps left by it – due to either too high risk or not large enough size. During the period 2008-2010, Islamic banks in Indonesia charged almost 50% higher financing rates than their conventional equivalents.

There is a lack of standard global guidelines and no single authority governing Islamic Finance, which means that in some cases a product is deemed Sharia compliant in one market and not in another – this is especially the case with Malaysian products, which are often deemed not Sharia complaint in the Gulf.

Unfortunately, due to events that are very much in the public eye every day, religious tensions and negative associations with Islam also exist. Particularly taking into account a closer integration with Sharia, Islamic Finance could be seen by some as a “back door” attempt to introduce Sharia to Western states where separation of the State and religion is a cornerstone of political and economic systems.

So although Islamic Finance has the potential to be applied to a wide menu of financial instruments and provide a viable, ethical system on a global scale, there are significant challenges that have to be met, including adoption of unified standards of accountability, transparency and efficiency.

If it can meet these challenges and is able to help mobilise a sizeable fraction of the “dead capital” then Islamic Finance might, as Turkey suggests, genuinely contribute the worldwide growth.

Dr Piotr Konwicki is a Senior Lecturer in Finance at the University of Bedfordshire Business School.

Courtesy: economia