Globalisation has to retune itself to needs of the time

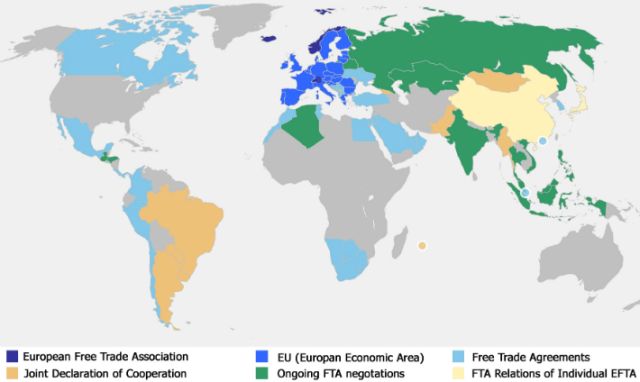

The tsunami of change was all-pervasive to engulf most of the nation states. Liberalisation, free trade, WTO, TPP, NAFTA, EFTA, EU, the information revolution et al came together and broke the historically defined geographical barriers. Isolationism became a hated and much maligned term in international trade, commerce and strategic considerations. There arose new hope of transnational job opportunities cutting across organisations and authorities.

The belief in the new world order was overwhelming with dreams of a better tomorrow where manmade restrictions would crumble, allowing unhindered migration of people, free flow of goods and technology and knowledge transfer, leading to the growth of the manufacturing and service sectors, employment creation and enhancement of living standards. The undercurrent was that the benefits would percolate down the line. Aspirations and ambitions were local but the vision was global in a wirelessly wired world.

Information and communication technology (ICT) clubbed countries together through the internet highway and, like a great medieval conqueror, created a one-world syndrome. However, the factors that were thought to be ushering in a new age of progress and prosperity turned out to be serious disruptors.

The developed countries witnessed the migration of jobs to the army of cheap labour in less developed countries, coupled with the huge inward migration of displaced people from war-ravaged countries, leading to unforeseen pressure on domestic tax payers.

Soaring unemployment levels, coupled with a fall in the real wage, broke the golden dream of sunny days in a free economy environment. Cities like Detroit, once bustling with industrial activities and manufacturing giants witnessed a slow death with the shifting of their nerve centres to a number of developing countries providing cheap and capable manpower.

Disenchantment grew in the rich countries against apparent loss of their sovereignty in the name of a borderless world which siphoned away their economic opportunities.

Things were no better in the developing countries either. No doubt shedding protectionism helped some of them garner production-line units and service sector benefits leading to absorption of both the skilled and semi-skilled human resource of the local pool.

Capital inflows improved but at a price. The volatile nature of such inflows impacted the economic decision-making process in these countries by integrating them to the frequent ups and downs of the rich economies.

Now, it seemed the developing countries had lost their economic sovereignty in the big empire of the virtual world. The unhindered flow of cultural values, ethics and lifestyles along the borderless internet highway generated a perceived fear and apprehension of being uprooted from their traditional social and cultural milieu — the fear of the big fish eating the smaller ones.

The apprehension was not only that Wal Marts would devour the kirana shops or McDonalds would alter eating habits through the likes of the McAloo tikki but that indigenous knowledge, traditions, religious beliefs and cultural milieu would all get swept away in the deluge. The fashion you favour, the apparel you approve, the music you compose, the food you relish, the opinions you form — as if all these have origins elsewhere in a society alien to your own and you feel an unknown and invisible ‘colonial power’ has stealthily demolished your sovereign boundary in the name of a connected world; as if the culture of the land is being swept away by a mighty cultural aggressor.

Part of such fear and apprehension may be perceived, part may be genuine but could lead to the redefining of nationalist ideas and interests in different parts of the globe.

The issues highlighted through Brexit in the UK, the stricter US immigration policy and the recent electoral agendas of several political groups in the EU and elsewhere are the inevitable fall out of this worldwide phenomenon.

Similar waves have hit the socio-political environment of a number of developing countries to rediscover and redefine their national identities so that the virtual borderless world does not demolish their geographically-defined sovereign borders and sweep away their unique cultural ethnicity.

All this has necessitated a fresh look at policy frameworks by suitably redesigning multilateral institutions so that local needs, ethos and pathos of the member countries are adequately reflected to ensure a win-win strategy. There should be sufficient prescriptions to ensure redistributive justice for the citizens so that inequalities perpetrated by the open economy architecture are taken care of.

Globalization has been there since birth of civilisation in different avatars. It has to retune itself to the needs of the time. After all, no nation would like to go back to the cocoon of isolation and monolithic existence.

(Kula Saikia, a Fulbright scholar and a Sahitya Akademy awardee, is Special Director General of Police, Assam. The views expressed are personal. He can be reached at kulasaikia@yahoo.com)

—IANS