Desert warrior, ignored prophet: Lawrence of Arabia’s life, legend and legacy

How is history made? From the interplay of political, social and economic forces, decisions made elsewhere or the contested “Great Man” Theory — the influence of one key man at the right place and time? For the modern Middle East’s making and its problems, all seem to play a role, including in explaining what Lawrence of Arabia accomplished — and the consequences of ignoring his advice.

As the entire Middle East is in greater turmoil than ever before, we should remember T.E. Lawrence, whose 129th birth anniversary was on August 17. More importantly, it is what lessons we can learn from him in the centenary of his biggest accomplishment — the Arab Revolt — though its outcome wasn’t what he wanted.

And history proves him right. British traveller and author Anthony Sattin, who has also written about Lawrence, says if he happened to come back and see today’s Middle East, he would say: “Told you so!”

But despite the reams written about him, most people only know of him through Peter O’Toole’s inspired, but misleading, portrayal in David Lean’s 1962 masterpiece. And despite its cinematic magnificence, “Lawrence of Arabia” does suffer from its medium’s limitations, which require condensing, simplifying or “jazzing up” reality.

For one, he wasn’t as tall, or as flamboyant, as O’ Toole made him to be. In the film’s beginning, asked by a reporter about Lawrence, American journalist Jackson Bentley says: “It was my privilege to know him and to make him known to the world. He was a poet, a scholar and a mighty warrior.” Adding later: “He was also the most shameless exhibitionist since Barnum & Bailey.”

While it was Lowell Thomas — whom the character represented as the American journalist — who made him famous through his pictures and film footage, Lawrence, who did contribute to his own legend, did not like this always.

The shy Lawrence was a much more complex, astute — and divided — man, possessing an insightful understanding of the Middle East’s intricate mosaic of clan and tribes and their intractability that few outsiders had. He was able to derive lessons from the current situation his superiors and government failed to see or ignored.

So where should we learn about him?

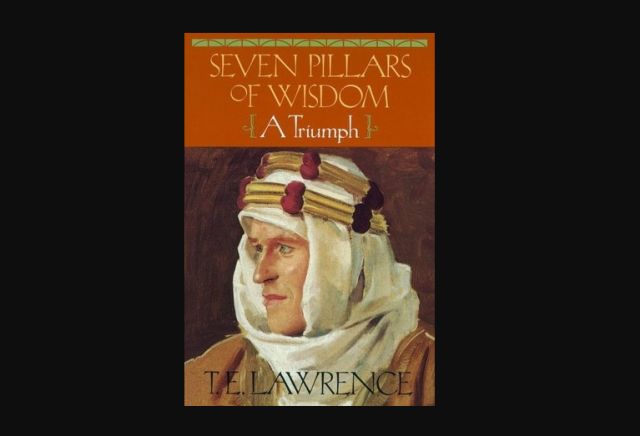

There is his own “Seven Pillars of Wisdom” (1926), published after some vicissitudes. But for all its lyricism, it is his version, with an eye on posterity. It was forestalled by Thomas’ “With Lawrence in Arabia” (1924), which Lean’s film drew on. Other biographies published in his lifetime included poet and novelist Robert Graves’ “Lawrence and the Arabs” (1927) and military strategist and historian B.H. Liddell-Hart’s “T.E. Lawrence in Arabia and After” (1934) — both drew on their subject for information.

While an authoritative biography by Jeremy Wilson (“Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence”) came as late as 1989, it seems better to see Lawrence reassessed at the zenith of chaos resulting from Britain’s betrayal of its promises to the Arabs, and the subsequent (colonial) settlement. But before this, we need to see the evolution of Lawrence himself.

This is done in Sattin’s “Young Lawrence: A Portrait of the Legend as a Young Man” (2014), which seeks to make Lawrence “a real person”. Covering aspects of Lawrence’s early life, skipped over or touched lightly in other biographies, it focusses on his birth (out of wedlock), his difficult relationship with a dominating mother, his deep affection for an Arab boy, his extraordinary journeys in the Middle East, and why he became an archaeologist and a spy.

Meanwhile, historian Lawrence James’ “The Golden Warrior” (1990, updated 2008) “penetrates and overturns the mythology” around Lawrence and seeks to “trace the sometime spurious Lawrence legend back to its truthful roots”.

His academic colleague James Barr’s “Setting the Desert on Fire: T.E. Lawrence and Britain’s Secret War in Arabia, 1916-1918” (2006) places the revolt Lawrence led against the wider context, its outcome — dictated by the Allies — and its implications from then to now, spanning from Mahatma Gandhi to Osama Bin Laden.

American journalist Scott Anderson’s “Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East” (2013) also takes the wider view, but supplements Lawrence’s activities with some friends and enemies operating in the same area at the same time, including an American geologist and a German secret agent.

Basically, Lawrence’s legacy can be summed in a dialogue from the film. As Prince Feisal tells him: “There’s nothing further here for a warrior. We drive bargains. Old men’s work. Young men make wars, and the virtues of war are the virtues of young men. Courage and hope for the future. Then old men make the peace. And the vices of peace are the vices of old men. Mistrust and caution. It must be so.”

But the world continues to pay a price.

(Vikas Datta is an Associate Editor at IANS. The views expressed are personal. He can be contacted at vikas.d@ians.in)

—IANS