by admin | May 25, 2021 | Opinions

Frank F. Islam

The killing of George Floyd has resulted in actions of various types against historical statues in the United States that may celebrate or demonstrate bigotry or racial bias. These actions have sparked a national conversation on what to do because of those statues.

In our opinion, the statues under scrutiny are America’s statues of limitations. They are part of America’s history. They communicate messages intentionally and unintentionally regarding the historical limitations of this nation and the persons they represent.

The statues that have been acted upon include not only the usual suspects, such as representations of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson, but also of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Ulysses S. Grant. What these actions have revealed is that what is in our American memories regarding these figures may be incomplete and/or inaccurate. Consider the following examples.

Many of the statues that have been assailed fall into a category known as Lost Cause Confederate Statues or Monuments. The majority of these statutes were erected in the South in the early 20th century with the support of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Their purpose and placement were to reposition the Civil War defeat as a valiant and worthy effort, as well as to ensure that whites returned to power while black progress and the potential for integration was retarded.

White superiority and racially insensitive attitudes in the U.S. have not just been restricted to the South. In spite of all his notable accomplishments, Theodore Roosevelt considered blacks inferior to whites. There is a statue of Roosevelt mounted proudly on a horse with a Native American on one side and a Black American on the other side that has stood at the entrance to the American Museum of Natural History since 1940. Because of its hierarchical depiction, the optics of that statue have been a cause for concern and controversy for some time. On June 21, the Museum asked the city to remove Roosevelt’s statue from its entrance.

Likewise, on June 28, Princeton University decided to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name from the building that has housed the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at the University. According to Princeton President Christopher L. Eisgruber, the Board of Trustees made that decision because, “…racial thinking and policies make him an inappropriate namesake for a school or college whose scholars, students, and alumni must stand firmly against racism in all its forms.”

In 2020, the times are changing. Statues that have survived over a century are being removed, toppled, defaced, or otherwise confined, if not to the dustbin of history, to an uncertain fate. The question becomes what is the proper manner to deal with the remaining statues that for a variety of reasons may be offensive.

Some advocate destroying or warehousing them. The Washington Post advises in an editorial to make it a matter for public discussion. The Post observes that this should not be the province of “… a crowd in the middle of the night, consisting not always only of good faith protesters but also of chaos-hungry opportunists.” Instead, it recommends, these “…are determinations suited for democratic and deliberative decision-making.”

We concur with the Post’s position. We would take it one step further, though, because this is about much more than statues. This is about American history.

It is a chance to make the historical record complete and to promote learning among current generations and for generations to come. This is a teachable moment and it needs to be treated as such.

That is the point Pulitzer Prize winning art critic Holland Cotter makes in his article for the New York Times in which he writes, “…the disposal of monuments should be approached case by case…It’s necessary for history’s sake, that we first stand back, look hard and sort them out.”

In his piece, Cotter proposes that the Roosevelt statue be removed from the entrance at the National History Museum and displayed in a slightly modified version accompanied by a detailed historical examination and explanation of it in one of the Museum’s galleries. In its editorial, the Washington Post states that while some statues might go into museums, “Others might reside in an outdoor space committed to cataloging a disgraceful era; Lithuania’s Grutas Park displays more than 80 statues that communists installed when the country was controlled by the U.S.S.R.”

The importance of viewing these statues in a historical perspective is highlighted by the debate regarding the “Great Emancipator” Statue — also called the Freedmen’s’ Monument — of Abraham Lincoln in Lincoln Park in the Capitol Hill area of Washington, D.C. The statue was erected in 1876 and shows Lincoln standing with the Emancipation Proclamation in his hand over a kneeling black man who is breaking his chains.

Protesters have recently called for the removal of the monument because it does not project the proper image of the black man in relationship to Lincoln. D.C. Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton has questioned the statue’s design. And, D.C. mayor Muriel Bowser has stated that the city should debate the removal of the statue.

What makes this debate of particular import is that the iconic black leader and orator Frederick Douglass spoke at the unveiling of the Emancipation memorial. Douglass was equivocal in his praise for Lincoln in his commentary. On the one hand, he said,

… we, the colored people, newly emancipated and rejoicing in our blood-bought freedom, near the close of the first century in the life of this Republic, have now and here unveiled, set apart, and dedicated a monument of enduring granite and bronze, in every line, feature, and figure of which the men of this generation may read, and those of after-coming generations may read, something of the exalted character and great works of Abraham Lincoln, the first martyr President of the United States.

On the other hand, he said:

Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man. He was pre-eminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men. He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country.

What Douglass was saying was that Lincoln was not perfect and he was providing a history lesson in his dedication remarks. It is a lesson worth hearing and learning.

Most Americans have only a superficial knowledge of history and much of what we have learned has been filtered through a white lens. This is a chance to change that, not by revising or rewriting the history of the United States, but by getting history right and presenting it through a technicolor lens and in 3-D.

One of the ways this can be accomplished is by putting together a collection of photos and readings or a book on the Statues of America similar to the book John Meacham and Tim McGraw authored, Songs of America: Patriotism, Protests and the Music That Made a Nation. In his New York Times article, Holland Cotter reports that in 2019 the American Museum of Natural History produced a documentary on the Theodore Roosevelt statue “…which details the work’s history and includes commentary by contemporary ethnologists, social historians, art historians and artists.”

Imagine something comparable available to the America public for information and educational purpose. Imagine a segment of a civics or history curriculum for students in their later elementary and middle school years devoted to America’s statues, to inform and inspire them to inquire about why the statues exist, what they represent, what stories they tell, what stories they do not tell, what new stories need to be written, and how actions should be taken to address past deficiencies and discriminations.

Imagining does not change things but not imagining means that nothing ever changes. In the year 2020, the United States appears to be poised to address its statues of limitations. This should be a monumental undertaking structured to engage all concerned and caring citizens. To maximize its impact, the undertaking should reach students in classrooms when their essential knowledge, skills and dispositions, and enduring values, attitudes and beliefs are being shaped.

Properly prepared and equipped, those students will shape the nation’s future. They will create a more inclusive and perfect union. They will construct America’s statues of tomorrow as ones of opportunity and equality and not of limitations.

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Opinions, World

Frank F. Islam

By Frank F Islam

The protests across the nation after the killing of George Floyd highlighted and brought significant attention to the huge racial divide between whites and blacks in this nation. There is another huge divide that has not received nearly as much coverage this year as it has in the past. It is the economic divide between corporate CEO’s and line level employees.

On May 27, Equilar released its 2020 pay study of CEO’s at S&P 500 companies, which it conducts annually for the Associated Press (AP). The study revealed that the median income of those CEOs was $12.1 million, an increase of 4.1% from 2019.

The CEOs received an increase of 7.2% in 2019 and 8.4% in 2018. So it looks like they are hurting a little. That may be true for them comparatively, but not compared to the average line-level employee.

In September 2019, the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) reported that the projected median pay raise for those line workers in 2020 would be 3.0% and the actual median in 2019 was 3.0%. SHRM commented that “…wage growth isn’t accelerating much despite record low unemployment…”

In his article, written in May 2019 after the Equilar/AP CEO Pay Study was released, AP Business Writer Stan Choe observed, “But the last time the jobless rate was almost this low, in the late 1990’s, hourly pay rose at 4% to 4.5%.” Choe pointed out, “…it would take 158 years for the typical worker at most big companies to make what their CEO did in 2018…”

An Equilar/New York Times study disclosed that the CEO median pay ratio (comparing CEO pay to the median pay for employees) as 277:1 in fiscal year 2018 and 275:1 in fiscal 2017. This new Equilar study in conjunction with the SHRM data suggests that gap continues to widen.

The economic divide continues to grow as a fault line that could eventually destroy our American democracy and the capitalist system it has supported. What accounts for this divide, which could become a chasm?

It came about more than four decades ago, when corporate America or big business shifted from a multiple stakeholder focus (shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers and communities) to a singular focus on maximizing shareholder value and rewarding CEO’s disproportionately for doing that. This changed the American economic landscape.

As we have written, it led to the offshoring of millions of good paying jobs, reducing the size of the incumbent workforce, and restructuring jobs from full time into part-time positions. It also led to the creation of tax havens, stock buybacks, and business consolidation. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which reduced the corporate tax rate, put more money into the corporate coffers, some of which was used to buy back stock and drive share prices even higher.

In mid-August of 2019, it appeared that corporate America might be changing its singular focus and renewing its commitment to America writ large. At that time the Business Roundtable, an organization comprised of America’s largest corporations, redefined its statement of purpose.

The statement was revised from placing primacy on shareholders alone to promoting “an economy that serves all Americans.” This new focus expanded the scope of stakeholders to include employees, customers, communities, and suppliers.

We were skeptical back then about the sincerity of that statement. We remain skeptical today as we approach one year since the Roundtable’s statement was issued. That’s because we have seen no plan for, and scant evidence of, a broad-based big business movement in the direction espoused in the Roundtable’s redefined statement of purpose.

It is far too soon to determine the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic will have on reducing the enormous gap between CEO and employee pay. Early indications are, however, it will not be positive.

The stock market is rebounding. And, in many instances, has little correlation to a business’ monthly or quarterly performance. If this continues, it will drive shareholder value up.

Jobs that were done at home during the pandemic by fewer people will most likely never return to the office. Robots, artificial intelligence, and automation will replace humans in routine service and high contact positions. This will drive wages down.

More specifically, Amazon has eliminated its COVID-19 hazard pay. Brooks Brothers, which is widely known for its “Made in America” brand, has announced it may be closing American factories in Garland, NC; Haverhill, MA; and, New York City. And Raytheon Technologies is cutting worker pay by 10% and reset the stock related payouts for corporate executives, which means that its CEO Gregory J. Hayes could earn millions more in income. These corporate actions obviously harm employees.

There is no question that the consequences of the pandemic, the catastrophic economic collapse, and the racial protests will have a long term and lasting impact on American business and the American economy. This is a time of crisis but, in a strange way, it is also an opportunity

It is an opportunity to ask the question, in the business domain: what should matter? Should it be shareholder value or stakeholder value?

It is an opportunity to ask: what are our American values? Are they inclusiveness and equal opportunity for all? Or are they economic segregation and inequality?

It is an opportunity to eliminate the economic fault line. It is a chance to turn it into the starting line for implementing new corporate and public policies and practices that shape “an economy that truly serves all Americans.”

by admin | May 25, 2021 | Opinions, World

Frank F. Islam

By Frank F Islam

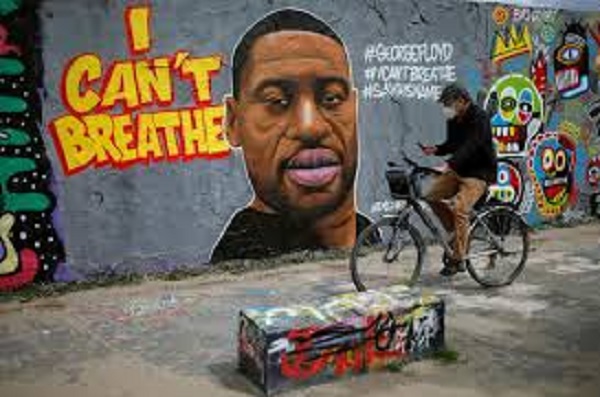

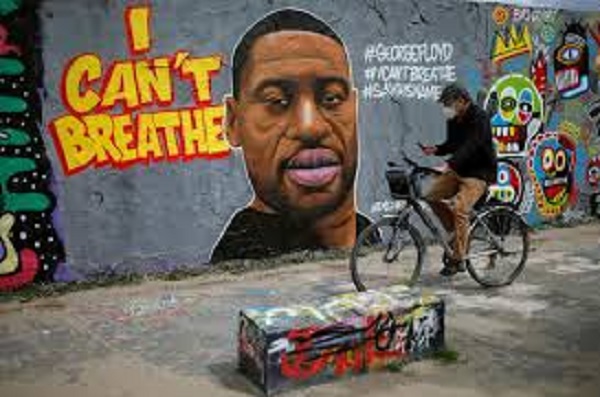

Since the brutal death of 46-year-old African American George Floyd at the hands of a white Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, the United States has witnessed civil strife of the kind not seen in more than five decades. In a video that has been streamed around the world millions of times, Chauvin is shown kneeling on Floyd”s neck for nearly nine minutes, even as the black man is heard crying, “I can”t breathe.”

For several years running up to Floyd”s death, American society has been a combustible mix of racial and political divisions, ready to explode. In the past four months alone, two young African Americans lost their lives to racial violence and police brutality in two highly-charged incidents.

In February, 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery was killed in southeastern Georgia, while jogging, by a white father and son who chased and fatally shot the African American man. In March, Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old emergency medical technician, was shot and killed by cops in Louisville, Kentucky.

Floyd”s death became a trigger that brought hundreds of thousands of American citizens to the streets protesting. Under the broad banner of Black Lives Matter, a movement that fights systemic racism, inequality and violence against African Americans, these protests spread to hundreds of cities across the country and around the globe.

While the protests have largely remained peaceful, in a few cities they resulted in riots and looting. Police enforced curfews and used tear gas leading to fatalities and injuries.

These protests bring back memories of the mid to late 1960s when there were racial protests and riots in several major American cities in response to police violence and racial incidents. As then, the public mood is one of discontent and dissatisfaction. According to a new Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll, 80 per cent of Americans feel that the country is spiraling out of control.

There are some major differences, however, between the chaotic events of the 60s and today”s turmoil. The current chaos is occurring at a time the country is dealing with the worst health crisis in its history and resulted in the catastrophic collapse of the economy.

The 60s protest movement happened under the watch of President Lyndon Baines Johnson who signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, one of the most progressive legislative measures in the history of the country. The law banned discrimination based on race, colour, religion, sex, and national origin, and increased minority political participation.

The current protests are unfolding under the watch of a president, whose actions have worsened life for ethnic and religious minorities in the country, and undermined democracy and institutions.

While the political polarization and coarsening of civic discourse predate Trump, they have dramatically declined during the nearly 41 months he has been in power. President Donald Trump is perhaps the most divisive president since Andrew Jackson who left the White House 183 years ago.

Trump is singularly focused on keeping his base happy, rather than being a president for all Americans. An influential part of that base, unfortunately, includes a large segment of America that is still stuck in the Antebellum South.

The Republican Party has been communicating in dog whistles on race and immigration since the presidency of Richard M. Nixon who won the office in 1968 by running as the “law and order” candidate. The Trump era has injected the mainstreaming of anti-immigrant rhetoric and Islamophobia.

So where will America go from here?

There is no doubt that there is systemic racism and injustice in America. That is not good news. There is good news though in what these protests portend for the future of America and all of its citizens.

Unlike the 60s, when those in the streets were primarily blacks, those protesting in 2020 are of all hues. Among them, there are Americans of all backgrounds and heritage, including whites, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Indian and other South Asian Americans. Millions have made their voices heard by coming together in a coalition through protests and speaking out for a more just and inclusive and tolerant America.

In less than five months, they and tens of millions of other concerned and caring citizens who want to extinguish systemic racism can change the country”s trajectory by voting and consigning Trumpism to history. Putting a new president in place will start the process of healing the country”s wounds and reducing the structural violence against blacks and other minorities.

In addition, the protesters have forced the country to take a fresh look at race relations and police brutality. As a result, many cities have begun to redefine the way local police are doing their job through a shift toward community policing.

Another source of optimism is the 244 years of America”s history. Every time the country has taken a regressive step, it has followed with several steps forward.

The nation has been led in the past by Presidents such as Jackson, Nixon and Trump, who tried to erase progress toward racial equality. America”s story has also been written by leaders such as Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, Jr., John F. Kennedy and Barack Obama, who have brought the country and its citizens together in the collaborative pursuit of the common good and a more perfect union.

The Negro spiritual and civil rights protest song of the 60s begins with these memorable words:

“We shall overcome, we shall overcome

We shall overcome someday

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe

We shall overcome someday.”

In 2020, this appears to be the day. Where America will go from here is on the journey to overcoming the racism that has shackled it since its establishment as a nation.